Left Ventricular Assist Devices and Kidney Function: An Overview for Nephrologists

I have a love-hate relationship with the left ventricular assist device (LVAD). On the one hand, these devices have quadrupled survival, from a meager six months to over two years, in patients with heart failure on inotropic support. On the other hand, patients who develop acute kidney injury (AKI) and require dialysis after LVAD placement have particularly high mortality rates and pose unique challenges with regards to renal replacement therapy (RRT).

The ventricular assist device was pioneered by Dr. Michael DeBakey in Houston, Texas. In 1966, the first successful LVAD was implanted in a patient who had difficulty weaning from heart-lung bypass machine. The patient enjoyed a complete recovery, only to die in an automobile accident six years later. Over the next several decades, improvement in engineering and technology led to the NIH artificial heart program and subsequent FDA approval of LVAD devices in the United States.

In a recent review published in AJKD, Roehm et al discuss the indications for LVADs and report on the impact these devices can have on kidney function. Currently, there are 2 main types of LVAD technology: HeartMate II (an axial flow pump design) and HeartMate III and HeartMate HVAD (centrifugal flow with levitating magnetic discs).

Schematic diagram of LVADs. A. An exploded view of the HeartWare Ventricular Assist Device, a centrifugal flow device (reproduced with permission of the copyright holder [American Health Association] from Aaronson et al). B. The HeartMate II device, a continuous-flow device with axial flow, and its location in the body (reproduced with permission of the copyright holder [Massachusetts Medical Society] from Slaughter et al).

Figure 1 from Roehm et al, AJKD.

- Bridge to transplantation – given the high mortality of severe congestive heart failure (CHF), the goal with bridge to transplant LVADs is to stay alive and healthy long enough to eventually receive a heart transplant.

- Destination therapy – device placement for the remainder of the patient’s life, even without heart transplant. Trials such as REMATCH (which implanted devices into non-transplant candidates) showed mortality and quality of life benefits in patients with severe CHF who received LVADs.

Given the expansion of implantation to include patients ineligible for heart transplantation, it should come as no surprise that LVAD use is increasing. Also increasing is the number of LVAD patients with concurrent kidney disease. CKD Stage 4 (eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2) is a general contraindication to destination LVAD, and patients on dialysis are an absolute contraindication. However, the hemodynamic effects of severe heart failure often lead to acute cardiorenal syndrome, and teasing out which patients may see improvement in renal function after implantation can be difficult. Compounding this issue is data from INTERMACS, showing that 12% of patients treated with VAD experience severe AKI (defined as new dialysis requirement or tripling of baseline serum creatinine). Despite the heterogeneity across reports looking at kidney function, what remains clear is that patients who develop AKI after LVAD therapy have a much poorer prognosis.

What about renal replacement therapy in patients who require dialysis after LVAD implantation?

In-center hemodialysis (HD) is the most used option, although many centers are resistant to LVADs due to the challenges of the device or the patient. These include low flow alarms, hemodynamic instability, and general lack of training/expertise regarding these devices. However, several case series have described successful HD in LVAD patients, particularly when dialysis providers are trained by advanced heart failure staff. Amazingly, there are even six case reports of successful AV fistula placement and maturation, despite the fact that blood flow in LVAD patients is non-pulsatile! These cases suggest that AV fistula creation is feasible and can be considered if the patient’s life expectancy justifies access creation.

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is also becoming a more palatable option moving forward. Earlier LVAD models potentially affected peritoneal integrity, thus placing these patients at high risk of peritonitis. With the newer models, this is a non-issue. PD offers the advantage of sparing venous access, decreasing bloodstream infections, and offers more hemodynamic stability with a longer duration of volume removal. Several case reports demonstrate the feasibility of PD in patients with newer LVAD models that maintain peritoneal integrity, and can be offered to motivated patients.

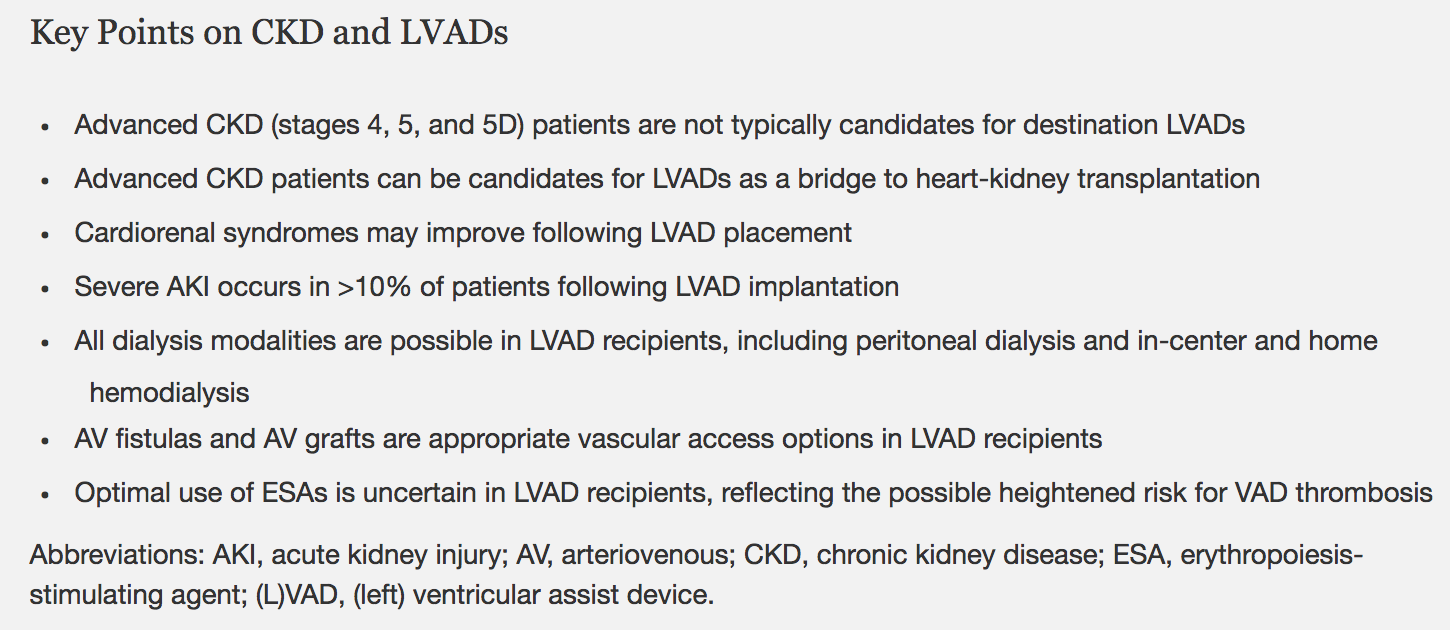

The takeaway points for this review are nicely summed up below:

Box 2 from Roehm et al, AJKD © National Kidney Foundation.

As the use of LVADs continues to grow, the authors should be commended for raising awareness of the unique issues pertaining to nephrologists.

To end this piece, let’s open a metaphorical Pandora’s box for us to consider as this therapy becomes more prevalent. Roehm et al note that patients with LVADs who develop AKI can be subsequently placed on dialysis successfully. Should ESRD patients on dialysis who develop CHF be considered for LVAD placement?

– Post prepared by Timothy Yau, AJKD Social Media Editor. Follow him @Maximal_Change.

To view the Roehm et al In Practice (FREE until March 12, 2018), please visit AJKD.org.

Title: Left Ventricular Assist Devices, Kidney Disease, and Dialysis

Authors: B. Roehm, A.R. Vest, and Daniel E. Weiner

DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.09.019

Thank you for this review, it is very useful information.