Congo Red: From Amyloid to Aspirin

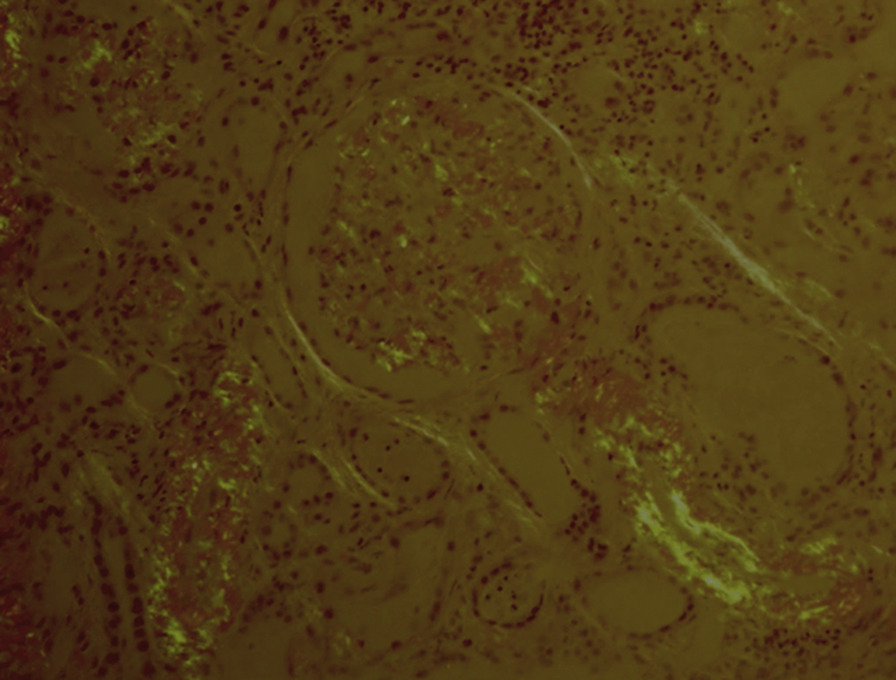

Congo red is synonymous with amyloidosis. The visually stunning apple green birefringence lights up the eyes and minds of pathologists and nephrologists.

AL amyloidosis with Congo red stain viewed under polarized light with apple-green birefringence of amyloid deposits in the glomerulus and arteries. Figure 5 from Fogo et al, AJKD, © National Kidney Foundation.

Like many histological stains, Congo red was originally a textile dye that was later used to stain pathological specimens. It originated in Germany in the 1880s and it was not until 1922 that its avid binding capacity for amyloid fibrils was discovered. Fascinatingly, it was initially used as a procedure – Congo red was administered intravenously to patients with suspected amyloidosis and if the concentration of the dye was low in the plasma sample drawn minutes later, it was assumed to have bound to amyloid fibrils in various organs and a diagnosis of amyloidosis was made. Decades later, it is still widely used to test pathological specimens for amyloid.

Like its name, the history of Congo red and the origin of its name have a colorful history. The ‘butterfly effect’ of the events during the development of Congo red had far reaching consequences including the establishment of an important precedent in intellectual property law and a prominent role in the birth of a ‘miracle’ drug.

Political Background

The year was 1884. The ‘scramble for Africa’ was at its peak. The European superpowers were trying to outmaneuver each other in the race to colonize Africa. Before the 1850s, many parts of Africa were known as the ‘white man’s graveyard’. Poisonous reptiles, malaria, large swathes of arid land, and the lack of medical facilities had brought exploratory Western missionary trips to a virtual standstill. This changed with the isolation of quinine from Cinchona by Pierre Pelletier and Joseph Caventou in 1820. The work of the French researchers unimaginably changed the history of Africa. Once a continent to avoid, Africa now became ripe for pursuit. King Leopold II of Belgium was first; Britain, France, and Portugal soon followed, fully utilizing their modern weaponry and engineering capabilities to expand their holdings in Africa.

Otto von Bismarck, a masterful politician and newly appointed Chancellor of the unified German Empire (1871), was keen to expand his country’s interests in Africa. This created tension amongst the other European superpowers, who wanted to avoid a direct conflict with Germany and each other at all costs. King Leopold II, having plundered the Congo basin, convinced the other nations that peaceful and cooperative trade in Africa was in everyone’s interests.

At the Berlin West Africa Conference in November 1884, representatives of 13 European nations and the United States (which had no interest in colonization) passed the Berlin Act. While ending African tribal slavery and indigenous development were discussed, most of the conference was dedicated to deciding ‘who gets what.’ The Congo Free State, where tax-free trade would be ‘allowed’ under the autocratic rule of Leopold II, was established. The rest of the continent was divided among the European nations. In the years that followed, Africa was pillaged; famine, war, imperialistic brutality, and western diseases killed millions of natives. In 1870, only 10% of Africa was colonized. By early 1900s, only 10% remained uncolonized.

Congress of Berlin by Anton von Werner. Lebendiges Museum Online

Congo Red – The Genesis

Meanwhile, the industrial revolution and scientific progress had vastly changed the social structure and culture prevalent among the common man living in the grand old nations of Europe and ushered in an era of liberalism. Clothing and fashion became centerpieces in the liberal movement. Dull, overbearing garments gave way to well-designed colorful tailored ‘made-to-fit’ practical pieces of clothing. Synthetic dyes replaced natural dyes which faded easily with light exposure. Aniline purple, the first synthetic dye, ushered in the ‘Mauve decade’ in the 1890s, making purple garments the rage in the fashion hubs of London and Paris.

Silk skirt and blouse dyed with Perkin’s Mauve Aniline Dye. Science Museum Group.

In 1883, Paul Böttiger, a young chemist working at Friedrich Bayer (then a chemical dye company), accidentally synthesized a brilliant red dye while in the process of trying to make a pH indicator. With his superiors showing little interest in the young chemist’s work, Böttiger left Bayer, patented the dye and offered it to other dye companies. After months of rejection, in 1885, he finally sold the patent to AGFA, a Berlin-based dye company and a major rival of Bayer.

AGFA recognized the value of the red dye. It was the first ‘direct’ dye – which meant that it did not require a substance known as a mordant to fix the dye to clothes. Imperialism was a sign of prestige in those days with newly colonized territories a hot topic of discussion on the streets. The Berlin conference coincided with the introduction of the red dye. As ‘Congo’ was the central theme of the conference, AGFA decided to use the name as a marketing ploy and Congo Red was born.

Patent Precedent

The economic impact was sensational: Congo red was so successful that it directly led to the bankruptcy of many AGFA rivals. Left out of the direct dye trade, Bayer was brought to its knees and plunged into an economic crisis; German newspapers reported its imminent collapse. In a last-ditch attempt at keeping the company afloat, Bayer came up with its own version of Congo red and immediately faced a patent lawsuit from AGFA. The companies reached a compromise and decided to share the profits from each other’s dyes.

Other chemical companies, angered by this, brought their own lawsuit against AGFA, arguing that the synthesizing process of Congo Red was ‘so obvious’ and hence it should be public domain and not patentable. The German imperial court’s ruling set a historic precedent for intellectual property law with their judgement: ‘While manufacturing processes/techniques can be patented, they should be non-obvious’.

The Birth of a ‘Miracle’ Drug

Saved from obliteration and now able to market their version of Congo red, Bayer’s fortunes immediately improved. Bayer’s ability to remain in business was crucial in another respect: it kept alive its research program, which had been working with an aim to develop new pharmaceuticals, and in particular, a marketable version of salicylic acid. While salicylate products had existed for decades, their use was limited due to the severe gastrointestinal side effects. With more money pouring in from Congo red sales, Bayer was able to hire new chemists. In 1897, two of these Bayer chemists, Eichengrün and Hoffman, came up with a major breakthrough: a new method to synthesize salicylic acid, with significantly fewer side effects. In 1899, Bayer marketed the new drug under the trademark Aspirin. A hundred years later, aspirin is celebrated as the most widely used drug in the world. The development of aspirin is hailed as a phenomenal pharmaceutical success and Bayer had Congo red to thank for that.

– Post prepared by Harish Seethapathy @BetterCallSeeth, AJKDBlog Guest Contributor, Renal Fellow at Mass General Hospital, and 2019 NSMC Intern

For more on this topic, check out the AJKD Atlas of Renal Pathology on AL Amyloidosis, as well as a recent AJKDBlog PathPointer on Congo-red-positive but amyloid-negative patients. In addition, this blog post is based on the article below – our thanks to Dr Steensma and Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine for their permission to use it:

Title: “Congo” Red: Out of Africa?

Author: David P. Steensma

Publication: Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine (www.archivesofpathology.org), February 2001, Vol. 125, No. 2, pp. 250-252

Interesting read