#NephMadness 2024: Toxicology Region

Submit your picks! | NephMadness 2024 | #NephMadness

Selection Committee Member: Diane Calello @DrDianeC

Diane Calello is the Executive and Medical Director of the New Jersey Poison Information and Education System (NJPIES) in Newark, NJ, and a Professor of Emergency Medicine at the Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. She obtained MD from Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, and completed all post-graduate training at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Her areas of specific interest include pediatric consequences of the opioid epidemic, public health implications of medicinal and retail cannabis programs, health implications and management of environmental lead poisoning, and public health response and investigation of toxic illness. This includes toxicosurvillance of vaping-associated pulmonary injury, pediatric edible cannabis exposures, and fentanyl and other illicit opioid exposures in young children.

Selection Committee Member: Marc Ghannoum @MarcGhannoum

Marc Ghannoum is a clinical nephrologist working at Verdun hospital in Montreal, Canada, and a clinical toxicologist working at the Dutch Poison Information Center in Utrecht, the Netherlands. He completed his fellowships in Internal Medicine and Nephrology at University of Montreal in 2002. He currently holds teaching positions at University of Montreal, NYU, and Utrecht University. He also chairs the EXTRIP workgroup who provides systematic reviews and clinical guidelines for the use of extracorporeal treatments in poisoning.

Selection Committee Member: David Goldfarb @weddellite

David S. Goldfarb is a Professor of Medicine and Physiology at NYU School of Medicine, Clinical Chief of Nephrology at NYU, Chief of Nephrology at the NY VAMC, and co-director of the Kidney Stone Prevention Program at NYU Langone Medical Center. Dr. Goldfarb is the former President of the New York Society of Nephrology and of the ROCK Society (Research on Calculus Kinetics). He received the “Stone Crusher of the Year” award in 2014 from the Oxalosis and Hyperoxaluria Foundation and the “Nephrologist of the Year” award in 2016 from the American Kidney Fund. He has been a consultant for the NY Poison Control Center since his nephrology fellowship in the 20th century. He is also an original member of the EXTRIP Workgroup, representing the NKF (https://www.extrip-workgroup.org/).

Writer: Jorge Eduardo Gaytan Arocha @JEGAYTAN90

Jorge Gaytan is a transplant nephrology fellow at Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán in Mexico City and nephrology attending at IMSS UMAE 71 in Torreon Coahuila Mexico. His areas of interest include glomerular diseases, transplant nephrology, interventional nephrology, POCUS, AKI, urine microscopy, cardiorenal and hepatorenal syndrome.

Competitors for the Toxicology Region

Team 1: Supportive Care and Antidotes

versus

Team 2: Extracorporeal Therapies

Image generated by Evan Zeitler using Image Creator from Microsoft Designer, accessed via https://www.bing.com/images/create, January, 2024. After using the tool to generate the image, Zeitler and the NephMadness Executive Team reviewed and take full responsibility for the final graphic image.

Poisonings are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide. In 2022, the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) reported over 2 million cases of human exposure to poisons. The nephrologist is often called to help in the management of patients, making crucial decisions for severe acid-base disorders, electrolyte abnormalities, acute kidney injury (AKI), and support with extracorporeal therapies.

In NephMadness 2024, the Toxicology in Nephrology Region comes strong with two great regions: Antidotes vs Extracorporeal Therapies, with a special focus on Nephrology. Are you ready for it? Let’s start with the table below, which summarizes the most common poisons and their physicochemical properties encountered in clinical practice.

Summary of Pharmacological Properties of Poisons and Drugs

|

Poison |

Molecular Weight (Da) |

Vd (L/Kg) |

Protein Binding (%) |

Metabolism and Excretion (%) |

Kidney Clearance (mL/min) |

| 32.04 |

0.6-0.8 |

Low |

~95 hepatic

~1 kidney |

5-6 |

|

|

62 |

0.5-0.8 |

Low |

~80 hepatic

~20 kidney |

20-30 |

|

| 151.2 | 1-2 | 25 | – | ||

| Acetylsalicylic Acid | 180.2 | 0.1-0.2 | 80-90 | ~80 hepatic

~20 kidney |

0.6-25 |

| Metformin | 129 | 1-4 | Low |

>90 kidney |

600 |

| Lithium | 73.9 |

0.7-1 |

Low |

>95 kidney |

20-40 |

|

780.9 |

5-8 | 20-30 | – | ||

|

454 |

0.3-1.2 | 35-50 | ~90 kidney | 50-200 |

Team 1: Supportive Care and Antidotes

Copyright: Maya Kruchankova/Shutterstock

Supportive Care

Management of poisoning begins with supportive care, which includes assessment of the airway, breathing, circulation, and neurological function. Most patients require volume repletion initially to correct hypotension, maximize tissue perfusion, and optimize kidney function to help eliminate some poisons (e.g., baclofen, methotrexate, lithium)

Sodium bicarbonate can be a supportive measure for metabolic acidosis and enhanced elimination through urine alkalinization. Poisons with the following characteristics are likely to exhibit enhanced elimination by urine alkalinization:

- It is eliminated unchanged by the kidneys

- It has a low volume of distribution (Vd)

- It has low protein binding

- It is a weak acid

A good example where urine alkalinization is helpful is in salicylate poisoning. It can also be used to enhance the elimination of some herbicides, methotrexate, chlorpropamide, and phenobarbital.

Gastrointestinal Decontamination

This intervention is time-dependent and should be initiated within the first hours of ingestion, depending on whether the poisoning is with extended-release medications. Activated charcoal (AC) is the most used medication for this purpose and often requires a nasogastric or orogastric tube to administer, so airway protection is necessary.

AC is useful for most poisonings, aside from those from alcohols, most metals (including lithium and iron), hydrocarbons, and corrosives.

Randomized controlled trials (RCT) investigating the use of AC in poisoned patients haven’t demonstrated a significant impact on crucial clinical outcomes. However, this perceived lack of impact is often attributed to methodological issues. In a prospective study with 808 variably poisoned patients, comparing those administered AC to those receiving no decontamination, no significant differences in clinical progression were observed. In addition, the group treated with AC exhibited higher rates of vomiting, intubation, and prolonged stays in the emergency department. Conversely, an observational study of 200 patients with acetaminophen ingestion indicated that those receiving AC within four hours had a lower risk of hepatotoxicity (OR 0.20).

Antidotes

An antidote is defined as a substance that can counteract the effect of a poison. They are direct or indirect agonists or antagonists to the effect of a poison. The mechanism of action can be the following: inhibitors of metabolism, binding for inactivation, and activity at the receptor.

The table below summarizes common antidotes used in clinical practice and their pharmacological properties. Notably, we should ask ourselves two important questions when it comes to antidotes:

- Does my patient have advanced kidney disease? If advanced CKD is present, we may need modified dosing of the antidote to avoid accumulation, and the indications for antidotal therapy may be affected.

- Is the antidote removed by extracorporeal therapy (ECTR)? If it is, a modified dosing of antidote will probably be needed post-ECTR.

Summary of Pharmacological Properties of Antidotes

|

Poison |

Molecular Weight (Da) |

Vd (L/Kg) |

Protein Binding (%) |

Clearance |

| 82.1 |

0.61 |

Low |

Kidney: 1 mL/min | |

|

N-acetylcysteine |

163.9 |

0.33-0.47 |

50 |

Kidney: 0.1-0.2 L/h/kg |

|

Flumazenil |

303.27 |

0.2-0.7 |

50-60 |

Dependent upon hepatic flow (0.8-1 L/h/kg) |

|

Naloxone |

363.45 |

1-3 |

54 |

– |

|

Folinic Acid (calcium folinate) |

511 |

17.5 |

54 |

~53 mL/min |

| 83,000 |

|

Fomepizole

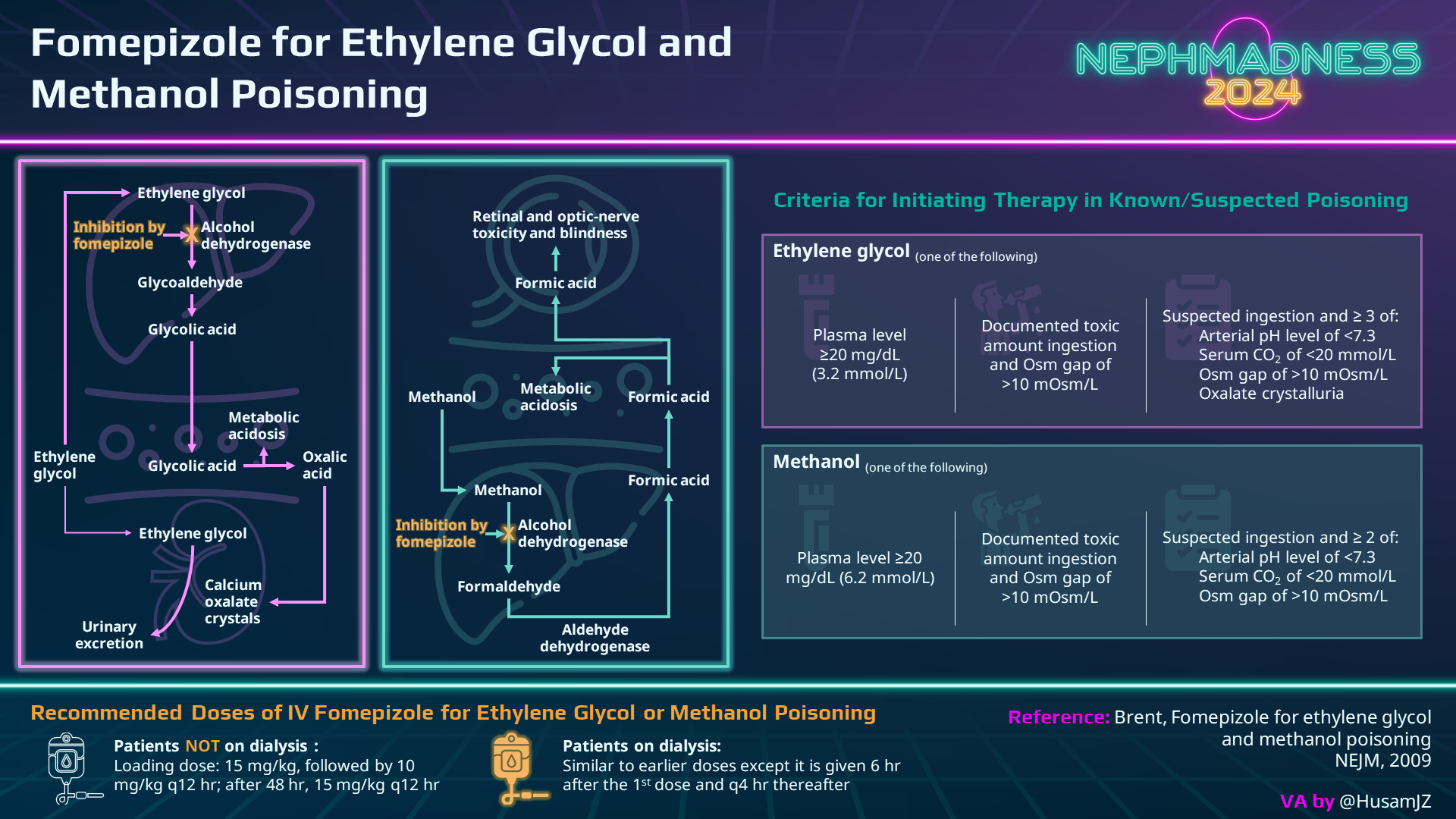

Fomepizole is the wonder antidote for poisoning to methanol and ethylene glycol as it prevents the metabolism of these toxic alcohols into harmful metabolites. It is a strong inhibitor of alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) with very high enzyme affinity (8,000 times that of ethanol). Several studies have demonstrated its benefit in methanol and ethylene glycol poisoning, especially if administered early during poisoning. The initial dose is 15 mg/kg, with follow-up maintenance doses of 10 mg/kg every 12 hours. After 48 hours, the dose is increased to 15 mg/kg. This adjustment is made because fomepizole has the potential to accelerate its metabolism through CYP450 enzymes. Additionally, it can be eliminated through dialysis, so the dose and schedule must be modified.

Fomepizole could be an additional treatment for acetaminophen poisoning as it is also a potent inhibitor of CYP2E1 and may also inhibit Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK), an enzyme involved in hepatotoxicity. In cases of acetaminophen poisoning, a few case reports showed favorable outcomes in patients at high risk of severe toxicity who received fomepizole treatment. A retrospective case series reported the use of N-acetylcysteine-fomepizole therapy in two acetaminophen-poisoned patients, suggesting that a dose of 15 mg/kg of fomepizole is sufficient to inhibit N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI) creation from CYP2E1. Additional case reports suggest the potential utility of fomepizole, especially in patients with acetaminophen levels exceeding 700 mg/L. Furthermore, a study involving human volunteers demonstrated a reduction in the generation of oxidative metabolites when fomepizole was administered after consuming excessively high doses of acetaminophen.

Ethanol

Unfortunately, fomepizole is not available in numerous countries, and therefore, alternative treatments are needed!! Ethanol, a competitive inhibitor of alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), was historically the favored antidote for toxic alcohols as it demonstrates a higher affinity for ADH compared to methanol or ethylene glycol. While many sources advocate for an absolute ethanol target level of 100 mg/dL to fully inhibit ADH, a more nuanced approach involves maintaining a concentration equivalent to one-quarter to one-third of the serum methanol or ethylene glycol concentration, expressed in mg/dL. This tailored strategy prioritizes a proportion relative to specific toxic alcohol levels rather than adhering to a fixed and arbitrary concentration of 100 mg/dL. Remarkably, while a cohort study comparing fomepizole to ethanol revealed fewer adverse events in the fomepizole group, this distinction is not addressed in prospective studies.

To achieve this therapeutic goal, it is advisable to use commercially available intravenous ethanol preparations. A suggested initial intravenous loading dose is 10 mL/kg of a 10% ethanol solution diluted in D5W (equivalent to 600-800 mg/kg of ethanol) aiming for serum ethanol concentrations of approximately 100 mg/dL. Following the loading dose, a maintenance infusion of 1 mL/kg/hour of the 10% ethanol solution should be initiated, with periodic ethanol measurements to monitor target levels. Unfortunately, intravenous preparations are not universally accessible.

Now, let’s explore the oral ethanol option! Typically, this involves a commercially prepared solution with hard alcohol. Administered via a nasogastric tube, it is recommended to use a 20% ethanol solution made with 100-proof hard alcohol, containing 40 g of ethanol per 100 mL. Here comes the recipe: Prepare the solution by mixing 500 mL of ethanol with 500 mL of D10W. Loading doses can go up to 800 mg/kg. However, it’s essential to highlight that a study involving healthy volunteers indicate that oral doses often fall short of achieving the intended serum ethanol concentration.

N-acetylcysteine

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) plays a crucial role in the management of acetaminophen poisoning by acting through various mechanisms. First, it inhibits CYP2E1, preventing the formation of N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI). NAC restores glutathione function, facilitating the detoxification of reactive oxygen species generated by NAPQI, and contributes to the cellular repair of damaged hepatocytes. It is a highly effective antidote when administered early in the majority of acetaminophen overdoses. However, nephrologists should consider specific scenarios:

- Metabolic acidosis: Large overdoses (>30 g) cause hyperlactatemia and metabolic acidosis resulting from mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired oxidative phosphorylation. These cases are usually equivalent to acetaminophen concentrations >700 mg/L, and NAC alone has limited efficacy in treating associated effects.

- AKI following severe acetaminophen overdose may prompt consideration of extracorporeal removal techniques.

- High anion gap metabolic acidosis due to 5-oxoproline. It’s an infrequent but classic complication that leads to an elevated anion gap metabolic acidosis.

Indications for NAC include the following:

- Suspected single ingestion >150 mg/kg or 7.5 grams, regardless of weight

- Unknown time of ingestion and serum acetaminophen concentrations >10 mg/L

- History of acetaminophen ingestion with any evidence of liver injury

Ongoing debates surround the most suitable method and duration for initiating N-acetylcysteine therapy post-ingestion. The widely utilized three-bag 20-hour intravenous protocol involves administering 300 mg/kg over 20 to 21 hours. It is performed as follows:

- Loading dose of 150 mg/kg IV over 15 to 60 minutes

- Subsequent dose of 50 mg/kg (6.25 mg/kg/hr) over four hours

- Final dose of 100 mg/kg (12.5 mg/kg/hr) over 16 hours

A simplified 20-hour (two-bag) intravenous protocol without loading dose has been proposed. It reduces systemic non-allergic anaphylactoid reactions (NAARs) and interruptions. In one study, NAARs occurred in 10% of the 389 patients treated with a standard regimen versus 4.3% of the 210 patients treated with a modified two-bag regimen (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.1-5.8). Another study reported shorter delays in the two-bag cohort compared to the three-bag cohort: median delay 35 min vs 65 min (p<0.01).

A modified, higher-dose NAC may be implemented in cases of massive overdose or delayed elimination. This generally involves increasing the dose in the second infusion from 6.25 mg/kg/hr to 12.5mg/kg/hr or higher.

Glucarpidase

Methotrexate toxicity can be seen with high-dose or low-dose regimens. High-dose regimens are defined as doses >500 mg/m2. Low-dose toxicity can occur from unintentional dosing mistakes in cases of kidney impairment. Factors such as duration of exposure, dosing frequency, cumulative dose, and the absence of folate supplementation contribute to the risk.

The initial steps in managing methotrexate poisoning involve drug discontinuation, intravenous hydration, and leucovorin (folinic acid) rescue. Leucovorin acts as the primary antidote by bypassing the dihydrofolate reductase blockade induced by methotrexate, enabling the restart of the intracellular folate cycle crucial for nucleotide synthesis.

A potential lifesaver in methotrexate poisoning is glucarpidase, a recombinant bacterial enzyme carboxypeptidase G2 (CPDG2). It can be used alongside leucovorin in cases of methotrexate poisoning with high drug concentrations. Glucarpidase rapidly converts extracellular methotrexate into inactive metabolites by hydrolyzing the carboxyl-terminal glutamate residue, leading to a swift reduction in methotrexate concentrations. This intervention proves particularly useful when standard measures like hydration and urine alkalinization are insufficient or when the patient is experiencing AKI. A single intravenous dose of 50 units/kg is recommended, achieving ~95% reduction in methotrexate concentrations within 15 minutes! It is a fast and effective intervention! In a cohort of 43 adults with kidney dysfunction and delayed methotrexate elimination, undergoing treatment with glucarpidase, only three of them required a second dose, administered 24 to 48 hours post-initial treatment. However, its specific indications and clinical benefit remain uncertain. Guidelines recommend the following:

- ≤24 hours after high-dose methotrexate: creatinine elevated relative to baseline measurement and:

- 36-hour plasma methotrexate concentration >30 microM

- 42-hour plasma methotrexate concentration >10 microM

- 48-hour plasma methotrexate concentration >5 microM

- 36 to 42 hours after high-dose methotrexate:

- 48-hour plasma methotrexate concentration >5 microM

While glucarpidase offers benefits, a notable drawback is its substantial cost, around $42,000 USD per 1,000 units, presenting challenges in terms of accessibility and timely availability. It’s crucial to note that methotrexate is considered moderately dialyzable by intermittent hemodialysis, but its use is not recommended, as the poison exerts its toxic effects intracellularly.

Navigating poisonings, particularly in the realm of nephrology, demands a comprehensive grasp of supportive care and antidotes. This year, supportive care and antidotes regions come strong to battle against extracorporeal therapies.

Check out this podcast episode of EMCrit with host Scott Weingart, NephMadness Exec Memeber Elena Cervantes, Marc Ghannoum, and Jorge Gaytán:

EMCrit 370 – Extracorporeal Therapies for Toxicology & Poisoning #ExTRIP #NephMadness

Team 2: Extracorporeal Therapies

Copyright: NoonBuSin/Shutterstock

The journey of hemodialysis (HD) in toxicology began in 1913, marking a breakthrough by effectively clearing salicylates from poisoned animals. Despite more than a century passing, the role of extracorporeal therapies (ECTR) in managing poisoned patients remains a topic of lively debate. Regional variations in ECTR indications for poisoning treatment further fuel this controversy.

Recommendations based on evidence and consensus for the utilization of ECTR in the management of poisoning have been issued by the EXtracorporeal TReatments In Poisoning (EXTRIP) workgroup. Notably, the consensus emphasizes the appropriateness of employing extracorporeal methods when there are clear signs of severe toxicity, when endogenous metabolism or excretion are impaired, and when dialysance of the toxin is known to be plausible.

This algorithm provides a stepwise approach to determine when and if so, which ECTR is appropriate for poisoning:

As nephrologists, it is crucial to have a comprehensive understanding of various ECTR principles and the physicochemical properties of poisons. This knowledge empowers us to prescribe personalized treatments and make informed adjustments to optimize poison clearance. It is important to adjust these strategies based on what’s available in our practicing institutions.

Hemodialysis

Hemodialysis stands out as one of the most readily available and rapid ECTR. It will always be the preferred ECTR option when we treat poisoned patients regardless of hemodynamics. The impact of ECTR on drug clearance is determined by the properties of the poison. These include molecular weight, protein binding, volume of distribution, and endogenous clearance. For example, favorable poison characteristics for efficient clearance during hemodialysis include:

- Molecular weight <10,000 Da

- Protein binding <80%

- Vd: <1-2 L/kg body weight

- Endogenous clearance <200 mL/min

- Water solubility of the poison

Poison clearance can be optimized during hemodialysis by using high-flux and large surface dialyzers, high blood flow, longer treatment times, and reduced recirculation from vascular access.

Hemofiltration (HF) has the benefits of hemodialysis (HD) and can remove even larger poisons, up to 50,000 Da. However, middle-cutoff (MCO) dialyzers can do the same because of their special membrane with more and larger pores. This means MCO dialyzers have higher permeability and better convective clearance.

Box 1 from Mullins and Kraut, AJKD © National Kidney Foundation.

Continuous Kidney Replacement Therapy (CKRT)

CKRTs can provide clearance via diffusion, convection, or both, depending on the modality. While covering these modalities is beyond the scope of this region, let’s review the unique characteristics of CKRTs:

- Continuous

- Low efficiency

In poisoning cases, CKRTs do not take the spotlight as the initial choice of extracorporeal treatments because their clearance is substantially lower than what a single session of hemodialysis can achieve. When a poison rebounds, moving from the intracellular to the extracellular space, it becomes suitable for dialysis. Despite the preference for redialyzing a patient, even when they are hemodynamically unstable (due to the toxin needing swift removal), considering CKRT after an initial HD session to manage the rebound can be a practical option. CKRTs as first-line ECTRs in poisoning have limited evidence.

Hemoperfusion

In hemoperfusion, poisons are removed from the blood by passing it through a charcoal or resin cartridge, where they are adhered or adsorbed. Unlike diffusion, adsorption is more versatile as it is not restricted by factors such as the molecular weight or protein binding of the poison. However, in comparison to hemodialysis, hemoperfusion comes with several drawbacks:

- Requires systemic anticoagulation

- Limited maximum blood flow rate of 350 mL/min due to hemolysis risk

- Non-selectivity: Platelets, white blood cells, calcium, and glucose are also adsorbed

- High cost and limited availability of hemoperfusion cartridges

- Cartridges need to be replaced every 2 hours due to saturation and decreased efficiency

- Ineffective for addressing electrolyte and acid-base imbalances, or fluid removal

Because of these factors, hemoperfusion use has decreased over the years. Several case reports suggest benefit from CytoSorb, a hemoadsorption device, although data are currently unconvincing.

Therapeutic Plasma Exchange (TPE)

TPE is a medical procedure that involves separating plasma and blood cells, replacing it with a solution containing albumin or fresh frozen plasma. TPE is distinct from hemodialysis as it efficiently eliminates highly protein-bound poisons (>95%), exceptionally large poisons (> 50,000 Da), and those with a low volume of distribution (Vd<0.2 L/kg). The effectiveness of poison removal depends on the time between poison administration and TPE initiation. In a TPE session, one plasma volume exchange removes approximately 65%-70% of the targeted poison from the intravascular compartment, with no additional clearance benefit beyond 1.5 volumes. The American Society of Apheresis recommends 1 to 2 plasma volume exchanges, using fresh frozen plasma or albumin as replacement fluids. The choice between these fluids depends on the poison’s preference for binding to plasma proteins or albumin, with certain drugs, like dipyridamole, quinidine, and chlorpromazine, having higher binding to α-1-acid glycoprotein, which is present in frozen plasma.

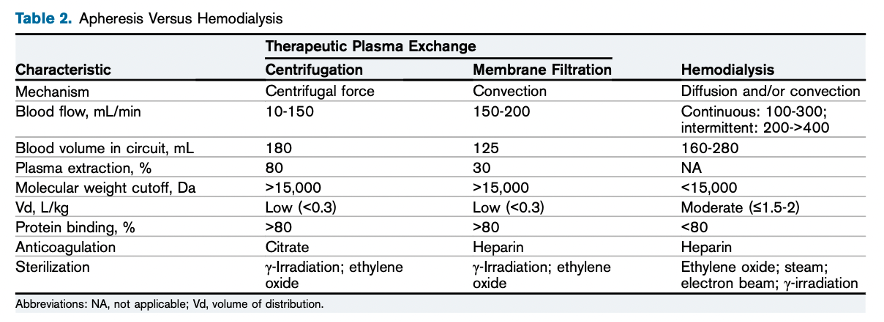

Apheresis Versus Hemodialysis. Table 2 from Cervantes et al, AJKD, © National Kidney Foundation.

Peritoneal Dialysis

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) has a restricted role in the management of acute poisoning, given that the maximum achievable clearance is less than 20 mL/min. One advantage of PD is its relative technical feasibility, especially in resource-constrained areas.

The use of ECTR in cases of poisoning is a therapeutic tool inherent to nephrology. Although antidotes can mitigate the need for ECTR by counteracting the effects of a poison, they are often used in combination. Take methotrexate toxicity as an example: ECTR is not recommended as the first line of therapy, but it may become essential in severe kidney failure. The first line therapy includes folinic acid, which re-starts the intracellular folate cycle necessary for nucleotide synthesis, and glucarpidase which converts extracellular methotrexate into inactive metabolites. However, it’s important to know that ECTR is capable of removing methotrexate. Understanding the characteristics of each therapy and poisons enables personalized treatment tailored to the specific situation. Extracorporeal therapies emerge as robust tools, empowering us to deliver targeted solutions for severe poisoning cases!

COMMENTARY BY ANITHA VIJAYAN:

The Battle for Detox

– Executive Team Members for this region: Elena Cervantes @Elena_Cervants and Anna Burgner @anna_burgner | Meet the Gamemakers

How to Claim CME and MOC

US-based physicians can earn 1.0 CME credit and 1.0 MOC per region through NKF PERC (detailed instructions here). The CME and MOC activity will expire on May 31, 2024.

Submit your picks! | #NephMadness | @NephMadness

Leave a Reply