#NephMadness 2025: CAR-T for Kidney Disease Region

Submit your picks! | @NephMadness | @nephmadness.bsky.social | NephMadness 2025

Selection Committee Member: Jeffrey Sparks @jeffsparks @jeffsparks.bsky.social

Jeffrey A. Sparks is a rheumatologist and Associate Professor of Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Sparks serves as the Director of Immuno-Oncology and Autoimmunity and Associate Program Director for the Rheumatology Fellowship of the Division of Rheumatology, Inflammation, and Immunity. His research focuses on using patient-oriented and epidemiologic methods to evaluate the etiology, outcomes, and public health burden of rheumatic diseases.

Yara Mouawad is a second-year nephrology fellow at the University of Texas Houston. She graduated from the LAU Gilbert and Rose-Marie Chagoury School of Medicine and completed her residency at Baton Rouge Medical Center in Baton Rouge, LA. Her areas of interest include glomerular diseases, kidney disorders during pregnancy, and medical education.

Competitors for the CAR-T for Kidney Disease Region

Team 1: CAR-T for Autoimmune Diseases

versus

Team 2: CAR-T Side Effects

Image generated by Evan Zeitler using DALLE-E 3, accessed via ChatGPT at http://chat.openai.com, February 2025. After using the tool to generate the image, Zeitler and the NephMadness Executive Team reviewed and take full responsibility for the final graphic image.

The first thing that comes to mind when we hear CAR (chimeric antigen receptors) T-cell therapy may be its groundbreaking success in treating refractory hematologic malignancies. But now, this revolutionary technology is being investigated to treat diseases with equally heavy tolls: autoimmune diseases. In this region, we will explore the history of CAR T-cell therapy up to its recent successes in treating select autoimmune diseases. We will also examine its limitations and potential side effects, leaving you with the question: Could CAR T-cell therapy be the winner in the fight against autoimmune disorders?

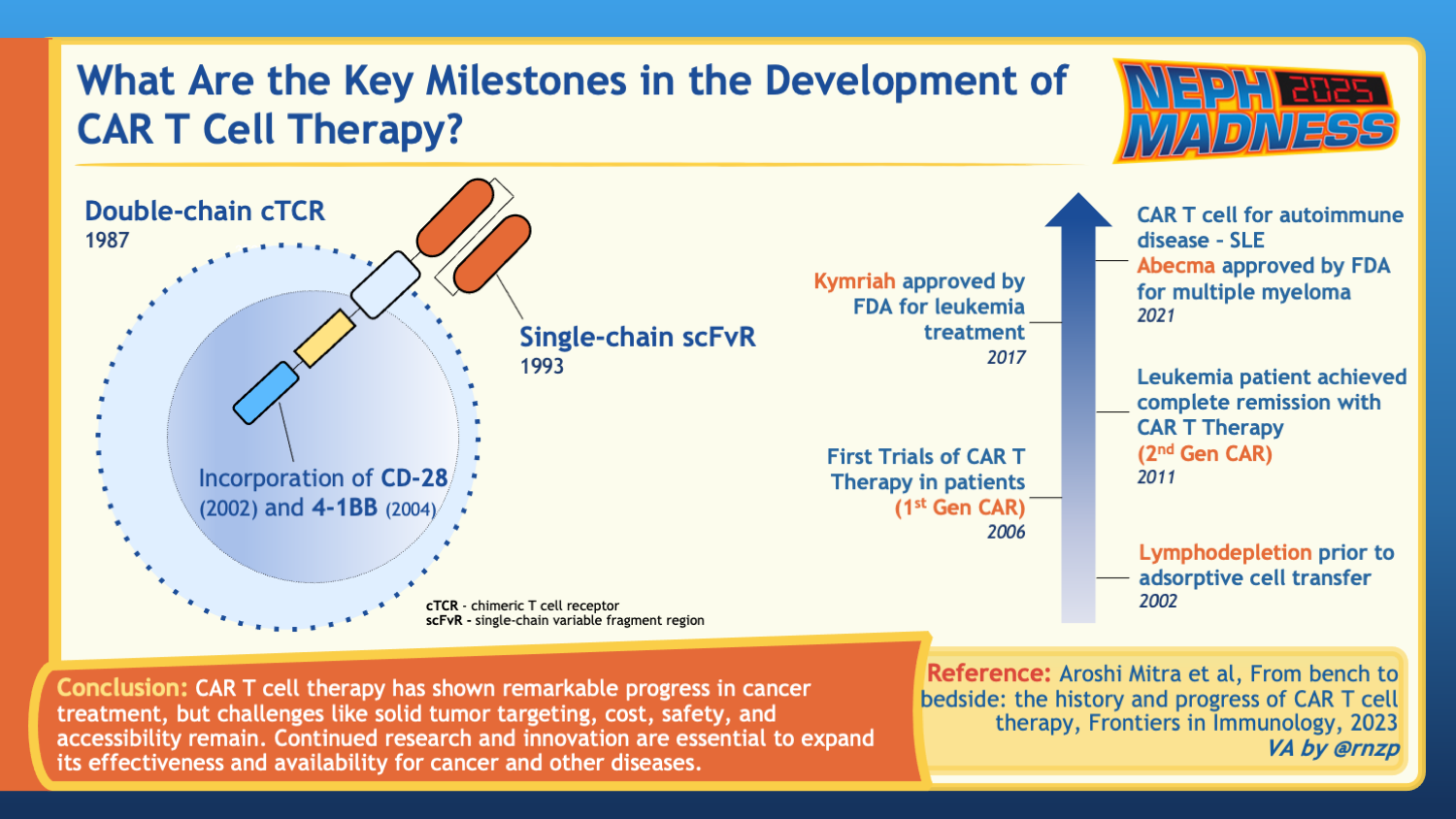

History of CAR T-Cell Therapy

The concept of chimeric T-cell receptors first emerged in the late 1980s in efforts to utilize our immune system against cancer cells. T lymphocytes play a central role in cell-mediated immunity by recognizing peptide antigens presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules on cell surfaces. Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) are fusion proteins combining B cells’ human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-independent antigen recognition with T cell-activating domains. These engineered receptors aim to redirect T-cells to target any prespecified antigen in a non-HLA-restricted manner. The first-generation CARs were constituted mainly of a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) fused to a lymphocyte intracellular signaling domain. While these engineered T-cells showed anti-tumor effects in the murine model, clinical trials using CAR T-cell therapy against ovarian and metastatic renal cell carcinoma did not show a reduction in tumor burden. This was presumed to be secondary to poor persistence and expansion of the infused CAR T-cells, evidenced by a rapid decline in their levels. In efforts to improve the proliferation and persistence of the engineered T-cells, a costimulatory domain was introduced into the model. Second-generation CARs combined the intracellular binding domain with the costimulatory endodomain, such as CD28. This construct demonstrated improved persistence and proliferation of CAR T-cells in vivo.

On August 30, 2017, the FDA approved the first CAR T-cell therapy developed by the University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) to treat B-cell precursor ALL (refractory or relapsed) in patients up to 25 years of age. More CAR T-cell therapies were later approved for the treatment of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and other B-cell malignancies.

Team 1: CAR-T for Autoimmune Diseases

Copyright: sirtravelalot / Shutterstock

New avenues for CAR T-cell therapy in the treatment of autoimmune diseases

Following the success of targeting CD19-expressing B-cells in treating relapsed or refractory B-cell malignancies, researchers began exploring CAR T-cell therapy for autoimmune diseases where B-cells play a crucial role in the disease process.

While autoantibodies are markers of many autoimmune diseases, they are only directly pathogenic in select diseases. In Graves’ disease, for example, autoantibodies against TSH receptors stimulate the latter and lead to hyperthyroidism. In autoimmune hypothyroidism and Myasthenia Gravis, autoantibodies play an inhibitory role by blocking their respective receptors. Autoantibodies can also form immune complexes, which deposit and trigger tissue inflammation and damage. The latter is seen in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, and cryoglobulinemia. B-cells also act as antigen-presenting cells in Type 1 diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis.

Targeting B-cells with monoclonal anti-CD20 rituximab proved effective in RA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and microscopic polyangiitis. Belimumab, which works by blocking B-cell activating factors and inhibiting B-cell survival and differentiation, improved disease control in SLE and lupus nephritis. However, studies examining renal interstitium, lymphoid tissues, and synovial tissues in patients treated with monoclonal antibodies found persistent B-cell infiltrates correlating with residual disease activity. And while CD19 is more widely expressed across pro B-cells to late plasmablasts, the use of anti-CD19 mAb presented the same limitations as anti-CD20.

As CAR T-cell therapy became more common in cancer therapy, its potential in the treatment of autoimmune diseases began to be explored. In a case report published in 2019, a patient with a 29-year history of antiphospholipid antibody was treated for refractory diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma (DLBCL) with CD19 CAR T-cell therapy. The patient’s anticardiolipin levels normalized after CAR T-cell treatment. At the 1 year follow-up, anticardiolipin levels remained normal, and the patient remained off anticoagulation without any incidence of venous or arterial thromboembolic events.

Meanwhile, researchers investigated the potential benefits of CD19 CAR T-cell therapy in mouse models of lupus. In these models, the effective depletion of CD19+ B-cells in inflamed tissues led to a significant reduction in antibodies targeting double-stranded DNA, decreased proteinuria, and improved survival rates in the mice. Indeed, it appears that the observed enhanced efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy stems from its ability to eliminate tissue-resident B clones effectively. This eliminates autoantibody-secreting plasmablasts and affects B cells’ antigen-presenting and cytokine-producing functions.

Further promising findings in CAR T-cell therapy have emerged from follow-up studies. A case series followed 15 patients with refractory systemic autoimmune diseases, including SLE, idiopathic inflammatory myositis, and systemic sclerosis. The study demonstrated rapid expansion of CAR T-cells and effective B-cell depletion, with most patients showing B-cell reconstitution within 100 days. All 8 patients with SLE met the criteria for low disease activity and achieved remission after 6 months, despite reconstitution of B-cells and disappearance of CAR T-cells. Impressively, all 15 patients remained in drug free remission at time of last follow-up (median of 15 months).

B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) is also expressed on mature B-cell populations, including memory B-cells, making it another target under investigation. CD38 is expressed on plasma cells, early B cells, and absent from mature B cells such as memory B cells, making it another desirable target in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Interestingly, in a patient with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy treated with anti-BCMA CAR-T, the B-cell lineage post CAR T-cell therapy showed a distinctively different B-cell receptor profile.

Making the right call: Who, when, and how to treat

As we’ve established, B-cell mediated autoimmune diseases, evidenced by autoantibodies and signs of B-cell tissue activity, are the prime candidates for current CAR T-cell therapies. Intervening with CAR T therapy carries the most benefit before the occurrence of permanent organ damage; however, given the known side effect profile, which will be discussed elsewhere, it remains reserved for patients who have failed two or more lines of immunosuppressive regimens. As more data are gathered regarding the safety of the treatment, utilizing this therapy in earlier stages may become more favorable, particularly in patients with poor prognostic factors.

Logistically, T-cells are collected from patients through apheresis. CD19 CAR T-cells are then generated through lentiviral transduction of the CAR encoding vector. Transduction is typically successful in only a fraction of the cell population, and therefore, once transduction occurs, cells are expanded using cytokine cocktails. These cells are then transported to the treatment sites, either fresh or frozen, to be re-infused into the patient.

Patients typically receive lymphodepleting chemotherapy, routinely cyclophosphamide (usually 0.75–1.5 g/m2) and fludarabine (usually 75–90 mg/m2 ), to optimize the chances of CAR T-cell expansion in vivo.

An important challenge to T-cell collection is that patients can be leukopenic due to their disease process and immunosuppressive regimens. Tapering of cytotoxic drugs can be considered in preparation for T-cell collection. The current recommendation is to pause non-glucocorticoid agents and tapering steroids to no more than 10 mg prednisolone equivalent daily. This may not be tolerated by all patients and “bridging” therapy may be needed while awaiting CAR T-cell infusion to prevent flares and worsening disease activity; glucocorticoids are the preferred option.

As expected, following lymphodepleting agents, patients may develop leukocytopenia and lymphocytopenia; therefore, antiviral prophylaxis with acyclovir and antibacterial prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is recommended.

Looking beyond the horizon

Researchers are already looking for more targeted strategies using CAR T-cell therapy. For example, utilizing Treg cells would allow for immunomodulation by suppressing both the activation of autoreactive T-cells and the production of autoantibodies by B-cells. This proves particularly efficacious in diseases such as SLE where autoantibodies against nuclear antigens initiate the cascade of immune complex deposition and inflammation. Indeed, in the mouse model, when Treg acquired anti-CD19 specificity was achieved they were able to suppress B-cells at their active sites, including solid organs such as lung and kidney, and reduce autoantibody production. Theoretically, the use of Treg cells may offer a better safety profile. The absence of cytotoxic mechanisms when compared to conventional CAR T-cell therapy reduces the risk of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) as well as opportunistic infections caused by chronic B-cell depletion. Yet, further data regarding the efficacy and long-lasting effects of this method is pending.

Allogenic CAR T-cell therapy is also gaining significant attention with its potential for quicker, more accessible, and broadly applicable treatments. Streamlined manufacturing to produce several batches of cryopreserved T-cells from one donor may potentially prove to be more cost efficient. These “off the shelf” therapies will also be more readily available for patients not having to undergo the lengthy process of autologous T-cell collection, CAR T production, and re-infusion. The two major concerns with allogenic therapy are graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) reactions, and lack of efficacy due to immune rejection of donor cells. Researchers, however, are already exploring ways to genetically modify these T-cells to be less immunogenic with lower risk of GVHD.

CAR T-cell therapy is thus a promising platform that could use other immune cell types, such as natural killer (NK) cells, or other antigen targets driving disease. One could even envision a personalized medicine approach to engineer CAR T-cells based on tissue biopsy of affected organs from autoimmune disease.

Nearly all autoimmune diseases are now being considered for CAR T-cell therapy; however, the current available evidence is limited to open-label, single arm trials, and thus far there are no controlled studies on CAR T-cell therapy for autoimmune diseases.

COMMENTARY BY ZAINAB OBAIDI:

CAR-T – The First of its Name

COMMENTARY BY JEFFREY SPARKS:

CAR-T for Autoimmunity – Driving to the Championship

In this podcast episode of GN in Ten, NephMadness Exec Dia Waguespack, rheumatologist Jeffrey Sparks, and nephrology fellow Yara Mouawad join host David Leverenz.

5.11 More Panelists Plus CAR-Ts in NephMadness

Team 2: CAR-T Side Effects

Copyright: Bits And Splits / Shutterstock

CAR-T Side Effects

As with any potent immune-based treatment, CAR T-cell therapy can cause a range of side effects, some of which can be severe and require careful management. The side effects of CAR T-cell therapy can be categorized into short-term and long-term effects. For our consideration, the short-term side effects of CAR T-cell therapy are the complications that can present as early as the first 48 hours after treatment up to the first few weeks after treatment, while the long-term effects are usually seen 3-4 weeks after treatment.

So far, severe toxicities associated with CAR T-cell therapy for treatment of autoimmune diseases have been quite rare compared to the oncology realm, but this could be confounded by the limited data that exist so far.

Short-term side effects

Cytokine Release Syndrome

The most infamous CAR T-cell therapy toxicity may be cytokine release syndrome (CRS). CRS is the result of extensive T-cell activation and massive cytokine release. Clinical manifestations include but are not limited to mild fever, respiratory failure, hypotension with/without circulatory collapse, and possible progression to multiorgan failure and death. The American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ASBMT) has published a grading system for CRS to standardize reporting of adverse events related to CAR T-cell.

In general, among the cancer population, around 70-90% of patients treated with CAR T-cell therapy experience some form of CRS, though the severity varies. More severe forms of CRS often correlate with greater baseline disease burden. From the early experiments of CAR T-cell therapy in autoimmune diseases, it seems that severe toxicities in general are infrequent. Indeed, from the follow-up of 15 patients with autoimmune diseases treated with anti CD19 CAR T-cell therapy, 11 patients developed grade 1 cytokine release syndrome marked by fever, and only one patient developed grade 2 CRS. This lower incidence of severe cases is presumed to be related to lower B-cell activity in autoimmune disease compared to malignant diseases. Targeted therapies such as anti-IL-6 tocilizumab have proven effective in the treatment of CRS without affecting the efficacy of therapy.

Immune-cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome

Immune-cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) is another serious complication linked to immune cell activation and cytokine release. Its manifestations range from confusion and aphasia to more severe cases of seizures and coma. In contrast to CRS, however, the exact mechanism is not fully understood, and treatment is usually supportive, often including corticosteroid therapy which may interfere with CAR T-cell activity.

Interestingly, several studies have noted the development of hypophosphatemia as a common occurrence with CAR T-cell therapy. Neurologic manifestations of hypophosphatemia, which often results from a substantial increase in metabolic demand, are very similar to those seen in ICANS. In a study looking at the association between hypophosphatemia and neurotoxicity symptoms in patients being treated with CAR T-cell therapy, authors found that in vitro activity of effector CAR T-cells leads to increased consumption of extracellular phosphorus. The authors also examined data from 77 patients treated with CAR T-cell therapy and found a correlation between incidence of ICANS and reduction of serum phosphorus levels, raising the question of whether phosphorus levels can be a monitoring and predictive tool for the development of ICANS, and whether addressing phosphorus deficiencies can improve outcomes in these patients.

From a kidney standpoint

To date, there are limited data when it comes to adverse kidney manifestations in patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy. In a case series report of 78 patients who received CAR T therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel or tisagenlecleucel, electrolyte abnormalities were common. Acute kidney injury (AKI), defined as 1.5x or greater increase in serum creatinine (SCr) within 30 days after CAR T therapy, commonly occurred within the context of cytokine release syndrome. Their findings also suggest that higher tumor burden at baseline may also be a risk factor for AKI.

Long-term side effects

Cytopenias and Hypogammaglobulinemia

From the data in oncologic literature, the most frequently observed side effects of CAR T-cell therapy include hypogammaglobulinemia, cytopenias, and infections. Long-term follow-up studies show that 25-38% of patients experience ongoing B-cell depletion for several years, while 18-74% have persistent immunoglobulin G (IgG) depletion. This can lead to an increased risk of infections, as well as potentially impaired response to vaccinations. Currently, no guidelines or recommendations exist regarding intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy in these patients. From the clinical data examining CAR T-cell therapy in autoimmune diseases, Grade 3 or 4 neutropenias and lymphopenias were mostly seen in the first 2 weeks of therapy and were attributed to the lymphodepleting agents given prior to CAR T infusion. However, there have also been observed cases of late neutropenias, occurring more than 4 weeks after treatment. Hypogammaglobulinemia was not a common occurrence, and infections recorded in the post-therapy follow-up period were mostly mild upper respiratory tract infections.

Ultimately, when evaluating the risk of infections in autoimmune disease patients following CAR T-cell therapy, it is important to compare it with the infection risk associated with traditional immunosuppressive treatments. This emphasizes the need for clinical trials to better understand both the relative efficacy and safety of CAR T-cell therapy.

Malignancies

As we’ve previously highlighted, the production of CAR T-cells most commonly occurs through lentiviral transduction. One potential risk associated with this technique is insertional mutagenesis. A report published in January 2024 mentions the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) investigating 20 reported cases of T-cell malignancies following CAR T therapy. However, the current data are limited, and it remains unclear if there’s a direct link between CAR T therapy and the emergence of secondary T-cell malignancies. Recognizing confounding risk factors such as prior therapies and primary malignancies is also important. Encouragingly, the incidence of T-cell malignancies in patients receiving CAR T therapy is considerably lower than in those undergoing traditional chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The current FDA recommendation is lifelong monitoring for any new malignancies in these patients.

Logistical Barriers

In the end, a treatment is only as effective as its accessibility. Although CAR T-cell therapy offers significant potential for treating certain autoimmune diseases, its accessibility is hindered by high costs, limited treatment centers, eligibility restrictions, and logistical challenges. The logistical barriers include institutional review board submission/approval, funding, facilitating novel collaborations with cell therapy specialists, equitable selection of patients, expertise in apheresis, and administration of chemotherapy lymphodepletion regimens during or just before a lengthy hospitalization where cell therapy is administered. These issues will need to be scaled prior to widespread implementation.

– Executive Team Members for this region: Dia Waguespack @d_r_waguespack and Anna Burgner @anna_burgner – @annaburgner.bsky.social | Meet the Gamemakers

How to Claim CME and MOC

US-based physicians can earn 1.0 CME credit and 1.0 MOC per region through NKF PERC (detailed instructions here). The CME and MOC activity will expire on June 1, 2025.

Leave a Reply