#NephMadness 2025: Disaster Nephrology Region

Submit your picks! | @NephMadness | @nephmadness.bsky.social | NephMadness 2025

Selection Committee Member: Mehmet S Sever

Mehmet Sukru Sever is an emeritus professor of Nephrology at Istanbul School of Medicine. His research focuses on kidney transplantation and disaster nephrology. Dr. Sever functioned as a field doctor and disaster relief coordinator, and also as renal team leader of Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) (Doctors Without Borders) in several mass disasters. Currently, he serves as the Chair in ERA-Kidney Relief in Disasters Task Force.

Rasha Raslan is a nephrologist working at Duke University Hospital in Durham, North Carolina. She also serves as the Assistant Program Director for the Nephrology Fellowship Program. Her clinical areas of interest include medical education, renal physiology and glomerulonephritis. She is also interested in the field of Disaster Nephrology, which focuses on the impact of both natural and human-made disasters on the care of patients with kidney diseases

Competitors for the Disaster Nephrology Region

Team 1: Kidney Care In Natural Disasters

versus

Team 2: Kidney Care In Conflicts

Image generated by Evan Zeitler using DALLE-E 3, accessed via ChatGPT at http://chat.openai.com, February 2025. After using the tool to generate the image, Zeitler and the NephMadness Executive Team reviewed and take full responsibility for the final graphic image.

“…all these men cry their doom across the world, meeting avoidable death…”

– Muriel Rukeyser, “Book of the Dead”

Disasters are serious disruptions of the functioning of a society, causing widespread human, economic, and environmental losses. They may occur due to a sudden major upheaval of nature or by the destructive action of humans. The major natural disasters are earthquakes, hurricanes, and floods, whereas the foremost man-made disasters are conflicts, terrorist attacks, and fires. In this series, we will be focusing on destructive disasters, excluding non-destructive catastrophes such as pandemics or droughts.

Definition and Evolution of the Concepts

Disaster nephrology is a specialized field focused on the complex management and coordinated care of patients with a spectrum of kidney diseases including those with acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) with and without kidney failure, during both natural and man-made disasters.

The association between disasters and kidney injury was first recognized after World War I, when a Japanese dermatologist, Seigo Minami, training in a German pathology lab, deduced that fatal kidney failure in several “buried” soldiers was caused by “autointoxication” from muscle protein breakdown. This concept was further developed by Eric Bywaters following the London Blitz during World War II who published a case series of a distinct form of oliguric renal impairment related to crush injury. We should not forget that the artificial kidney itself was introduced by Kolff during that time and was soon used to treat war-time AKI. The association between disasters and kidney failure was fully appreciated during the devastating Armenian earthquake of 1988, in which more than 600 victims suffered from crush-related AKI. The majority of these patients died due to lack of dialysis from poorly coordinated management. That’s when the terminology “renal disaster” was introduced and the Renal Disaster Relief Task Force (RDRTF) of the International Society of Nephrology was created.

After the Marmara earthquake in 1999, considering the high frequency of crush injury-related-AKI among earthquake victims, the term “seismo-nephrology” was suggested. In 2015, this concept evolved into “disaster nephrology” as a broader category. Since then, the field of disaster nephrology has continued to evolve to address challenges seen in patients with AKI and CKD in both man-made and natural catastrophes, with guidelines and international response committees addressing the unique needs that may arise with each. Most recently, American Society of Nephrology (ASN), the European Renal Association (ERA), and the International Society of Nephrology (ISN) launched the ASN-ERA-ISN Kidney Support Initiative to create a unified emergency response strategy and coordinate global preparedness to disasters for kidney community.

Team 1: Kidney Care In Natural Disasters

Copyright: BEST-BACKGROUNDS / Shutterstock

“Floods are ‘acts of God’, but flood losses are largely acts of man.”

With ongoing climate change, the frequency and severity of natural disasters such as hurricanes, heat waves, floods, and earthquakes are expected to rise. Natural disasters can sometimes be predicted several days in advance allowing for some degree of preparedness. While conflicts can last for extended periods of time, natural disasters occur over a shorter period: from seconds, like earthquakes, to days as with hurricanes.

Natural disasters cause widespread harm to the general population and pose an even greater risk for patients with kidney disease. AKI from crush injury in earthquakes is the second leading cause of death after direct trauma. In a large retrospective study of USRDS data, patients on dialysis had a higher mortality in the 30 days after a hurricane compared to non-dialysis patients, with the highest risk immediately after the disaster.

Spectrum of Kidney Problems

Acute Kidney Injury

The incidence of all types of AKI increases during disasters. Entrapped victims may suffer from prerenal AKI when under the rubble for long periods and become severely dehydrated. Also, massive bleeding due to vascular injury may result in hypovolemic shock and prerenal AKI. Postrenal AKI may develop in these patients as a consequence of supravesical or infravesical obstructions after pelvic trauma. Last but not least, intrarenal (both ischemic and toxic) AKI is quite frequent in disaster victims because of prolonged shock, sepsis, usage of nephrotoxic agents, and transfusion reactions. However, since overall management of these patients does not differ from patients with AKI seen during routine practice, crush injury related-AKI remains the focus of disaster-related AKI discussions.

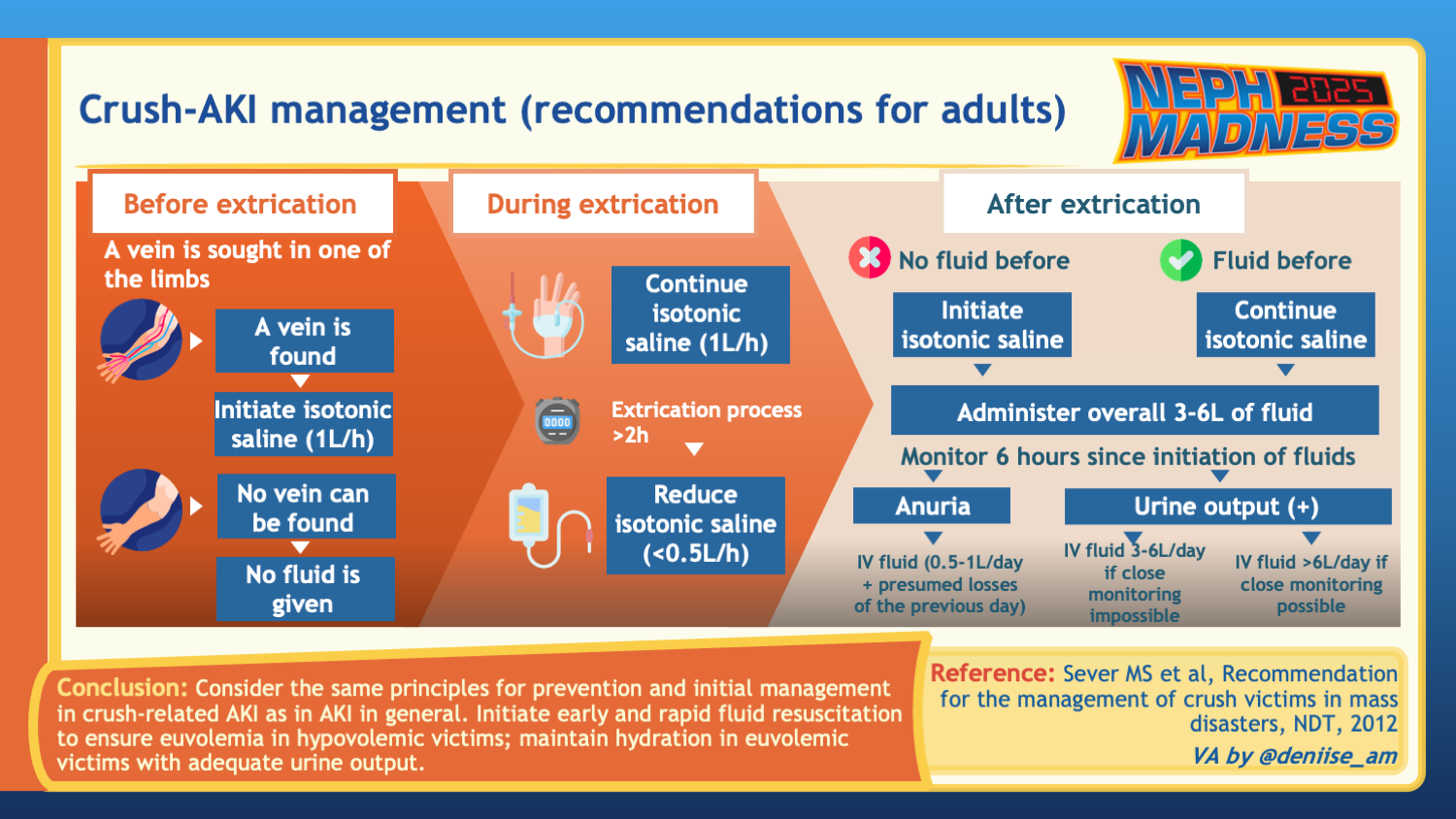

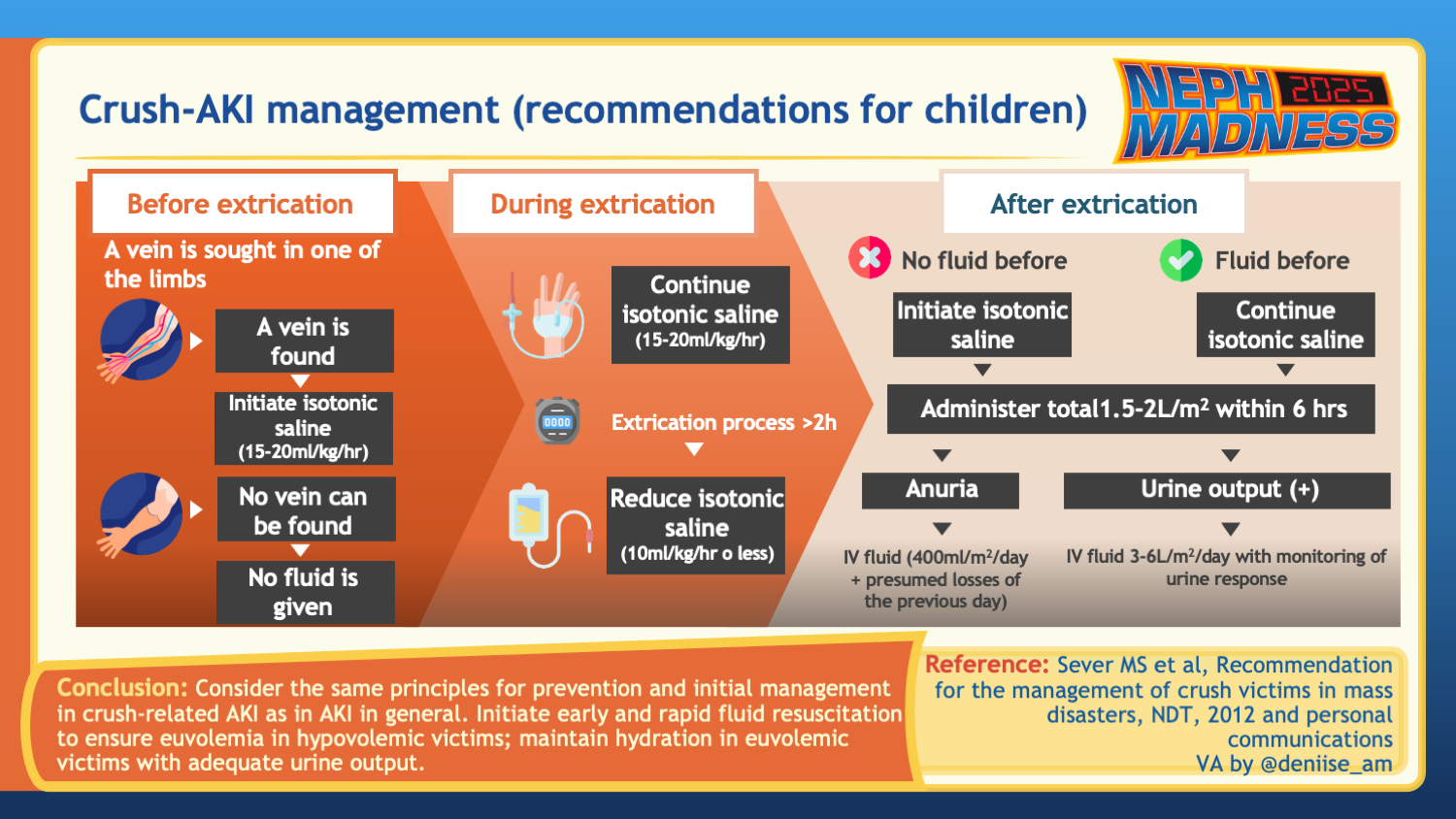

Crush injuries can lead to compartment syndrome-related hypovolemia and in turn rhabdomyolysis, characterized by the release of myoglobin from damaged muscles which then forms intratubular casts in the kidneys. This mechanism, combined with direct toxicity and also renal hypoperfusion, can lead to acute tubular injury. Elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) levels is a hallmark, with higher levels of CK often correlating with greater severity of renal injury. During disasters, clinicians often have to rely on clinical signs to diagnose rhabdomyolysis, such as dark urine and oliguria in the setting of crush injury. Traumatic rhabdomyolysis can evolve into a full crush syndrome with systemic manifestations such as AKI, hyperkalemia, hypotension, shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

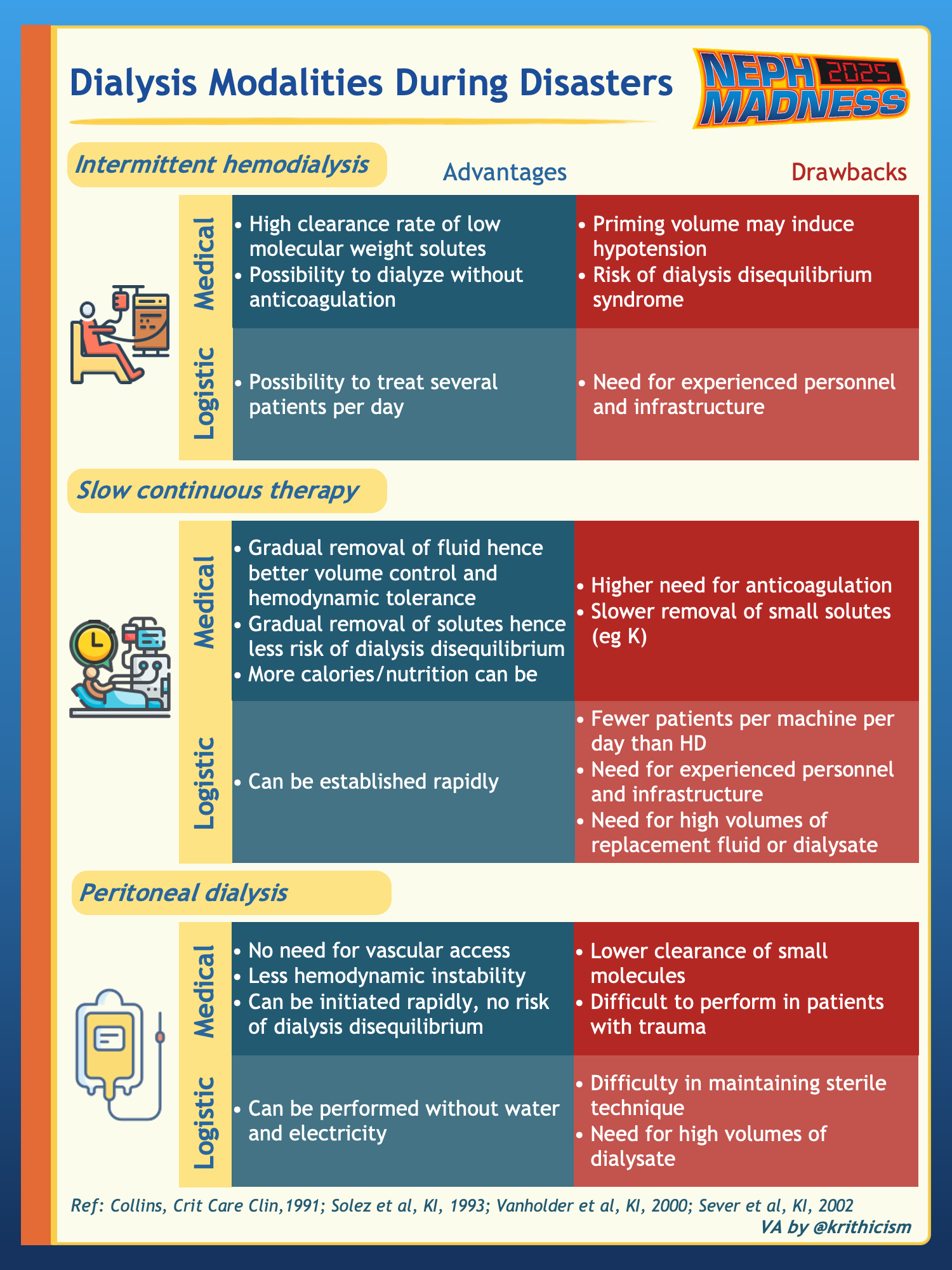

Management of crush-related AKI should begin even before the victim is extricated from the rubble. The cornerstone of treatment is early and aggressive administration of intravenous fluids, typically isotonic saline at a rate of 1 liter per hour. Monitoring urine output is essential to prevent hypervolemia. Fluids are later typically switched to a hypotonic-alkaline solution; potassium is empirically avoided. In the 1999 Bingol earthquake in Turkey, those who were aggressively fluid resuscitated were less likely to require dialysis. Intermittent hemodialysis is preferred over continuous renal replacement therapy or peritoneal dialysis for medical reasons (e.g., higher efficiency in treating hyperkalemia) and logistic reasons (dialyzing higher number of victims in a given time period).

CKD

Natural disasters can disrupt the ongoing treatment of CKD and associated comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension. Access to critical medications, including immunosuppressants, may be limited during these events.

End-Stage Kidney Disease on dialysis

Dialysis-dependent patients are at risk of missed treatments, electrolyte derangements, and infections. In cases where an acute disaster (such as an earthquake) occurs during a dialysis session, immediate action has to be taken to disconnect patients from the machine, sometimes by patients themselves, either by “clamp and cut” or “clamp and cap” techniques.

Dialysis units are vulnerable to power outages, and many lack emergency generators. In a survey of 81 dialysis centers, only 32% reported having a backup generator on site.

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) may appear more practical during natural disasters by eliminating the need for travel, but the primary challenge is the shortage of PD solutions and supplies. Power outages can also affect those that rely on an automated cycler.

Transplant recipients and those awaiting a transplant

Natural disasters often disrupt the ability to carry out transplant services. After Hurricane Katrina hit the southern United States in 2005, Louisiana saw a 21% decrease in kidney transplant activity since two of the three major transplant centers became non-operational. Other contributing factors included a shortage of medical supplies and burnout among medical personnel. It can take several years for a transplant center to regain its full capabilities.

In patients with a functioning allograft, the ability to obtain medications may be compromised, highlighting the need for stockpiling. Following hurricanes and floods, immunocompromised patients face an increased risk of waterborne as well as other communicable diseases due to unsanitary and overcrowded living conditions.

Risk mitigation, disaster management, and kidney care

Natural disaster planning and relief is considered in three phases: before, during, and after the disaster.

Before disaster

Patient preparedness plays a critical role in mitigating harms associated with disasters. Data from one prevalence study suggests that most patients on hemodialysis are not adequately prepared for a disaster, regardless of age, education, literacy, and socioeconomic status. Less than half of those surveyed knew of alternate dialysis centers or had sufficient medical records related to their dialysis treatment. In comparison, patients on peritoneal dialysis were better prepared for a disaster.

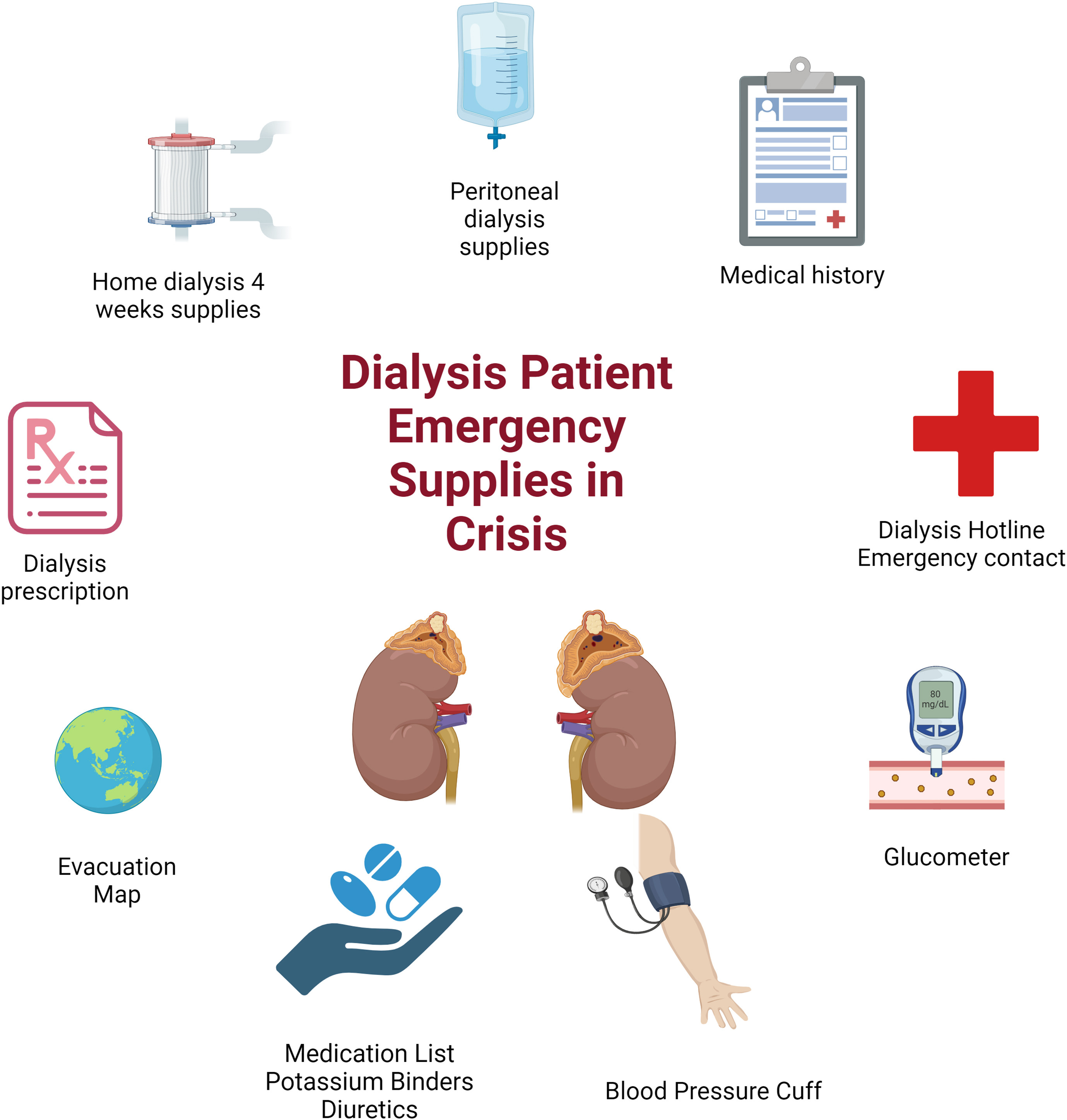

Those on chronic hemodialysis are encouraged to keep a printed document with their dialysis prescription and plan for alternate dialysis units should their regular facility become unavailable. Those on peritoneal dialysis are encouraged to stock up on supplies ahead of a natural disaster, aiming for at least one week’s worth. Patients who rely on a cycler should be educated on how to perform manual exchanges in the event of power outages.

Additionally, patients are encouraged to have emergency kits with essentials, as well as a stockpile of essential medications. This is particularly important for transplant recipients and those on critical medications when missing doses is detrimental. There are numerous national and international resources available to patients and providers on emergency response preparedness. In the United States, the National Kidney Foundation has a “Planning for Emergencies” guide for people with kidney disease.

Content of emergency kits for dialysis patients. Fig 2 from Alasfar et al, © National Kidney Foundation.

Content of emergency kits for transplant patients. Fig 3 from Alasfar et al, © National Kidney Foundation.

Dialysis units should engage in contingency planning for staffing shortages and conduct annual preparedness training in advance. They should also plan for power outages and identify other dialysis units that their patients could be referred to in case the unit becomes non-operational. In predictable disasters, performing early dialysis on some patients would allow them to go without treatment during a disaster. Pre-planned availability of generators and water tankers can make all the difference.

When disasters come with advance warning, activating volunteers, hotlines, and evacuation plans can help manage the potential chaos. When local organizations are overwhelmed, national and international relief agencies need to be contacted.

During disaster

During the chaos of disaster, it is prudent to follow previously established protocols to maximize efficiency and minimize adverse consequences. Disaster relief coordinators are responsible for gathering information on the status of local hospitals, dialysis units, and patients, while coordinating with other centers and national or international relief organizations.

In the field, a rapid assessment and triage process is crucial to identify patients that require urgent or specialized care. A key goal is to identify those who need to be evacuated and arrange for their transfer. Planned evacuation through an organization is preferred over the riskier self-relocation by patients. In situations where dialysis facilities are non-operational from power outage, water outage, destruction, or inaccessibility, possible solutions range from generators and water tankers (picture below) to mobile or temporary dialysis units.

Water tanker in front of a Fresenius Kidney Care Dialysis center in Richmond, VA, during an outage in January 2025. Photo by Rosalia Marshman.

Consensus statements recommend that transplantation programs continue during mass disasters, if feasible from a medical and logistical standpoint, unless there is an imminent risk of death to patient and staff. Telemedicine, if available, has the benefit of providing care when physical infrastructures are non-operational.

After disaster

Patients with AKI or CKD who have experienced a disaster should be evaluated and treated for undiagnosed complications and progression of the underlying diseases as well as elective medical problems which have been neglected during the disaster period.

Natural disasters can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and exacerbate existing depression in the general population, including among dialysis patients. The psychological well-being of healthcare workers can also be impacted. Screening for mental health conditions and addressing them in the post-disaster period is a priority. Additional key areas of focus include rehabilitation of affected patients and the re-establishment of regular nephrology services. Disaster relief organizations should evaluate the efficacy of the disaster response to inform future strategies and efforts.

COMMENTARY BY ARSHIA GHAFFARI:

The Los Angeles Wildfires and Kidney Care

In this podcast episode, hosts Anna Gaddy, Sam Kant, and Raphy Rosen dive into the emerging field of Disaster Nephrology with expert Mehmet Sukru Sever, nephrologist Rasha Raslan, and NephMadness Exec Anna Vinnikova.

NephMadness Region 8 Pod Crawl: Disaster Strikes, Nephrology Responds

Team 2: Kidney Care In Conflicts

Copyright: Ilya Andriyanov / Shutterstock

“War does not determine who is right – only who is left.”

-Anonymous

Wars versus natural disasters

While there are common aspects to both natural and human-made disasters, armed conflict-related ones are often protracted, sometimes lasting for years. Unlike natural disasters that can affect any region, wars and conflicts tend to occur in areas with already struggling infrastructure. These situations lead to widespread chaos and disorganization, insecure living environments, and limited resources.

Wars may also involve intentional sabotage of medical and civilian infrastructures as well as disruptions in the transportation of patients and medical supplies. A shortage of trained healthcare professionals can ensue due to their migration, displacement, or demise of themselves or their loved ones. The extent of population displacement in conflicts tends to be more severe than in natural disasters, with unclear timelines of return. Conflict zones can also become breeding grounds for infections due to unsanitary and crowded living conditions. All these factors present unique challenges for providing healthcare to chronically ill patients, including those with kidney diseases.

Spectrum of Kidney Problems

Acute Kidney Injury

Due to their chaotic nature, determining the exact incidence of AKI during conflicts is difficult, with reports suggesting a wide incidence range of 0.17-18%. Prerenal and subsequent intrinsic renal AKI (ischemic acute tubular necrosis) can occur secondary to massive bleeding from gunshot injuries. Exposure to noxious gases and toxic agents can cause direct toxic nephropathy. Hemoglobinuric AKI may result from incompatible blood transfusions given during the chaos of war. While crush injury-induced rhabdomyolysis is most commonly associated with natural disasters such as earthquakes, it can also be seen in conflicts that include heavy bombardment of civilian infrastructures and entrapment of civilians under the rubble.

Chronic Kidney Disease

Patients with CKD may not receive adequate treatment of their underlying medical conditions such as diabetes and hypertension due to lack of medications or medical visits. Similarly, the inability to abide by dietary recommendations can accelerate the decline in kidney function. The lack of access to immunosuppressive medications may cause relapse or worsening of underlying glomerular disease.

End-Stage Kidney Disease on dialysis

Outcomes for dialysis-dependent patients tend to be poor during conflicts. When possible, evacuating these patients to safer regions of the country or abroad needs to be performed, such as in the case of Ukraine. In many conflicts, such as in Syria and Gaza, dialysis schedules are reduced to twice or even once a week, with shorter treatment times. Under-dialysis and missed treatment sessions are associated with greater odds of hospitalization and mortality. Poor sanitation techniques lead to an increase of communicable diseases such as Hepatitis B.

Inability to place fistulas leads to a greater reliance on temporary catheters, which often remain in place for months. Patients with vascular access, due to the imminent need for evacuation during treatment, have to be educated on how to self-disconnect from the machine using “clamp and cut” or “clamp and cap” techniques to minimize the risk of extensive bleeding, hypotension, shock, and infection.

While PD may seem like a more attractive dialysis option during disasters due to the ability to perform manual exchanges without a cycler and without the need for trained personnel, it presents its own challenges. Similar to patients on HD, patients on PD are at increased risk of infection (e.g., exit site infections, peritonitis) because of overcrowding and unsanitary living conditions. A shortage of PD solutions and other supplies are common; as are unaffordable costs. Lack of electricity presents an additional challenge to those on automated peritoneal dialysis (APD).

Transplant recipients and those awaiting a transplant

The ability to perform transplant surgeries is severely affected during conflicts due to donor procurement constraints and a lack of transplant facilities and personnel. After the Syrian civil war erupted in 2011, there was a 60% decline in the number of kidney transplantation surgeries. Factors that contributed to this include migration of surgeons and nephrologists and lack of functioning transplant centers.

Patients with existing transplants face an increased risk of rejection due to the inability to obtain immunosuppressive medications and suboptimal follow up. Additionally, they are at higher risk of infections given unhygienic conditions during war.

Risk mitigation, disaster management, and kidney care

Similar to natural disasters, the management of conflict-associated kidney disease is discussed in three stages: before, during, and after the conflict.

Before conflict

Unlike some natural disasters that can be predicted several days in advance allowing for some degree of preparedness, most conflicts are unpredictable and can erupt with little to no warning. Pre-conflict disaster preparedness focuses on education and training of healthcare personnel and patients on self-security issues and best practices in resource-limited situations. Patients should also be educated on stockpiling medications and adhering to dietary restrictions.

During conflict

Fluid management in conflict crush victims is similar to earthquake crush victims. Treatment of the victims typically begins in the field with IV (non-potassium-containing) crystalloids, even before extrication of the entrapped. Recognizing patients who are unresponsive to fluids and starting dialysis early can prevent severe electrolyte derangements and death.

Field hospitals are often established to triage and temporarily treat acute cases. However, due to the complexity of injury-related AKIs, field hospitals may not be adequately equipped to manage these injuries, requiring patient evacuation to areas with more specialized care.

Patients that are dialysis-dependent are particularly vulnerable as they may miss treatments due to displacement or lack of functioning dialysis clinics. The latter can occur due to damage to infrastructure and facilities, as well as lack of trained personnel. Treatment of complications of ESKD, including anemia, hyperparathyroidism, and malnutrition are often not considered in these resource-limited settings. Relying on dietary and fluid restriction and potassium binders can mitigate the need for dialysis.

In some cases where communication lines are still functional, using telemedicine for consultancy with physicians in other countries can mitigate existing personnel shortages. In one example, staff and physicians used social media applications such as WhatsApp to consult with nephrologists and non-government organizations (NGOs) outside the country.

Medical personnel fatigue and burnout is particularly prevalent in conflict zones, where healthcare workers face long hours, in resource limited settings with critically ill patients, often at great risk to their own safety. Carefully rotating schedules and asking for assistance from physicians and personnel from other regions, countries, and NGOs can help mitigate the burnout. Well-organized help in the form of established NGOs is vital to save lives, whereas unsolicited help may be not useful or even harmful by exaggerating the extent of logistic problems.

After conflict

Since many non-urgent medical issues are neglected during active war time, post-disaster planning should focus on re-establishing care for those with chronic diseases. Addressing mental health related conditions that may have developed due to the conflict should also be a priority. Organizing debriefing meetings to learn from past experiences can improve disaster response by better planning for future crises.

COMMENTARY BY MELVIN BONILLA-FELIX:

Disaster Nephrology in Focus

– Executive Team Members for this region: Anna Vinnikova @KidneyWars – @kidneywars.bsky.social and Ana Catalina Alvarez @catochita – @catochita.bsky.social | Meet the Gamemakers

How to Claim CME and MOC

US-based physicians can earn 1.0 CME credit and 1.0 MOC per region through NKF PERC (detailed instructions here). The CME and MOC activity will expire on June 1, 2025.

Submit your picks! | @NephMadness |@nephmadness.bsky.social | NephMadness 2025 |

Leave a Reply