#NephMadness 2025: Genetics Region

Submit your picks! | @NephMadness | @nephmadness.bsky.social | NephMadness 2025

Selection Committee Member: Jordan Nestor @thenestor.bsky.social

Jordan Nestor, Assistant Professor of Medicine at Columbia University, specializes in hereditary kidney diseases. Her research advances precision nephrology by expanding genomic testing access and developing tools for non-expert clinicians to use genomic data in personalized care, with a focus on addressing health disparities.

Matthew Gross is a second-year nephrology fellow at Johns Hopkins. He completed his medical degree at Wayne State University and his internal medicine residency at the University of Pittsburgh. His professional interests include bioengineering, dialysis, and medical education.

Competitors for the Genetics Region

Team 1: Genetics in FSGS

versus

Team 2: Genetic Counseling

Image generated by Evan Zeitler using DALLE-E 3, accessed via ChatGPT at http://chat.openai.com, February 2025. After using the tool to generate the image, Zeitler and the NephMadness Executive Team reviewed and take full responsibility for the final graphic image.

Team 1: Genetics in FSGS

Copyright: vchal / Shutterstock

“Roads? Where we’re going, we don’t need roads.” When it comes to the genetics of kidney disease, we’re zooming ahead to the future of nephrology, as well as appreciating how far we’ve come in this field.

We’ve all cared for patients with a pattern of injury termed focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and have asked ourselves questions like, Is this a primary or secondary process? When is genetic testing appropriate? To dig into these questions, let’s start with the basics: what exactly is FSGS?

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis is a histologic pattern of injury characterized by scarring in parts (segmental) of some (focal) glomeruli. It can be a manifestation of both primary disease and a resultant injury from other etiologies. As a result, the classification step is crucial for determining therapy options. FSGS can be classified into the following types:

- Primary FSGS: Thought to be caused by a circulating permeability factor that is toxic to the podocyte, although the identity of the circulating factor(s) is yet to be identified.

- Adaptive, virus-associated, and toxin-associated FSGS: Commonly referred to as “secondary FSGS,” this is thought to develop as a maladaptive response to conditions such as obesity, diabetes, chronic infections (such as HIV), and drug toxicity (such as pamidronate).

- Hereditary FSGS: Attributed to deleterious variants in numerous genes, particularly those involved in podocyte and glomerular basement membrane structure and function. Key examples include COL4A3/4/5 (Collagen Type IV Alpha Chain) and NPHS1 (Nephrin) / NPHS2 (Podocin).

- APOL-1 associated FSGS: Linked to genetic variants in the APOL-1 gene. Currently identified are two risk alleles (G1 and/or G2) that contribute to toxic effects in podocytes.

The incidence of FSGS is increasing in the United States, accounting for an estimated 20%–35% of adult patients undergoing biopsy for evaluation of proteinuric kidney disease.

Before diving deeper into the genetic factors, testing criteria, and potential implications for patients and providers, let’s first discuss some basic genetic definitions and terminology. An allele is a variant form of a DNA sequence at a specific genomic location. A gene can have multiple genetic variants, including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), which can result in different alleles. Since humans inherit one copy of each chromosome from each parent, they typically inherit two alleles for each SNV within a gene. These alleles can be identical or different, and the combination of alleles influences traits or the likelihood of developing certain conditions. Consequently, genetic inheritance can be sex-linked (X-linked or Y-linked), autosomal dominant (AD), autosomal recessive (AR), or mitochondrial (maternal). AD diseases require only one pathogenic allele for expression, whereas AR diseases need pathogenic changes present in both copies of a gene – known as a biallelic mutation. A heterozygous mutation means that only one of the two alleles carries a specific mutation. In some cases, an individual may carry two different pathogenic variants in the same gene, known as a compound heterozygous mutation, which can occur in either a cis or trans configuration. In the trans configuration, the two mutations are inherited from different parents and occur on separate copies of the gene, often leading to full expression of an AR disease. In the cis configuration, both mutations are inherited from the same parent and occur on the same copy of the gene, which may have different clinical implications depending on the function of the unaffected allele. X-linked conditions, more prevalent in males, involve mutations on the X chromosome, with heterozygotes showing variable disease expression in females.

Various zygosities of disease-causing mutations. Adapted from Kelly et al.

Genetic related causes

The occurrence of genetic FSGS varies significantly across different populations and geographical regions. Let’s review the more common genes with mutations known to cause genetic FSGS.

NPHS1/2

NPHS1 encodes nephrin and NPHS2 encodes podocin – both key proteins involved in podocyte cell signaling and forming the slit diaphragm. Mutations in either gene typically follow an autosomal recessive pattern with high penetrance and early onset. Early onset disease associated with NPHS1 mutations is commonly referred to as nephrotic syndrome of the Finnish type.

ACTN4, TRPC6, and other genes

Mutations in the ACTN4 (Actinin Alpha 4), TRPC6 (Transient Receptor Protein 6), and INF2 (Inverted Formin 2) genes (among others) have all been implicated in hereditary FSGS, usually following an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with gain of function mutations. The protein ACTN4 cross-links actin filaments, which, in the context of podocytes, helps maintain the filtration barrier. The TRPC6 plays a role in regulating calcium influx into podocytes. The protein INF2 is a member of the formin family, regulating actin dynamics (mutations with INF2 are also associated with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease).

COL4A3/4/5 associated nephropathies

The Alport spectrum diseases, including Alport syndrome, thin basement membrane disease, familial hematuria, and a hereditary form of isolated FSGS, are caused by deleterious variants in the COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5 genes. These genes encode the collagen IV α3, α4, and α5 chains, which together form a heterotrimer essential to the structure of basement membranes in the glomerulus, cochlea, and eye. As a result, these conditions can present with varying degrees of kidney involvement (potentially leading to kidney failure), as well as auditory and/or ocular abnormalities.

Inheritance of Alport spectrum diseases

Inheritance patterns for Alport spectrum diseases vary depending on the type of genetic variant. The COL4A3 and COL4A4 genes are located on chromosome 2, specifically at the 2q35-37 region, whereas the COL4A5 gene is located on the X chromosome. Accordingly, these diseases are associated with heterozygous variants in COL4A3, COL4A4, or COL4A5; biallelic variants in COL4A3 or COL4A4; or hemizygous variants in COL4A5. The isolated FSGS phenotype is typically associated with heterozygous variants in COL4A3 or COL4A4.

Inheritance patterns in Alport Syndrome

Alport syndrome, a major condition in the Alport disease spectrum, is classically inherited in three patterns:

- X-linked Alport syndrome (XLAS): The most common form, where affected males generally have more severe disease than affected females due to hemizygous COL4A5 variants.

- Autosomal recessive Alport syndrome (ARAS): Caused by biallelic variants in COL4A3 or COL4A4, this form presents with similar severity in both males and females.

- Autosomal dominant Alport syndrome (ADAS): Caused by heterozygous variants in COL4A3 or COL4A4, this form also affects males and females equally in terms of disease severity.

APOL1-associated disease

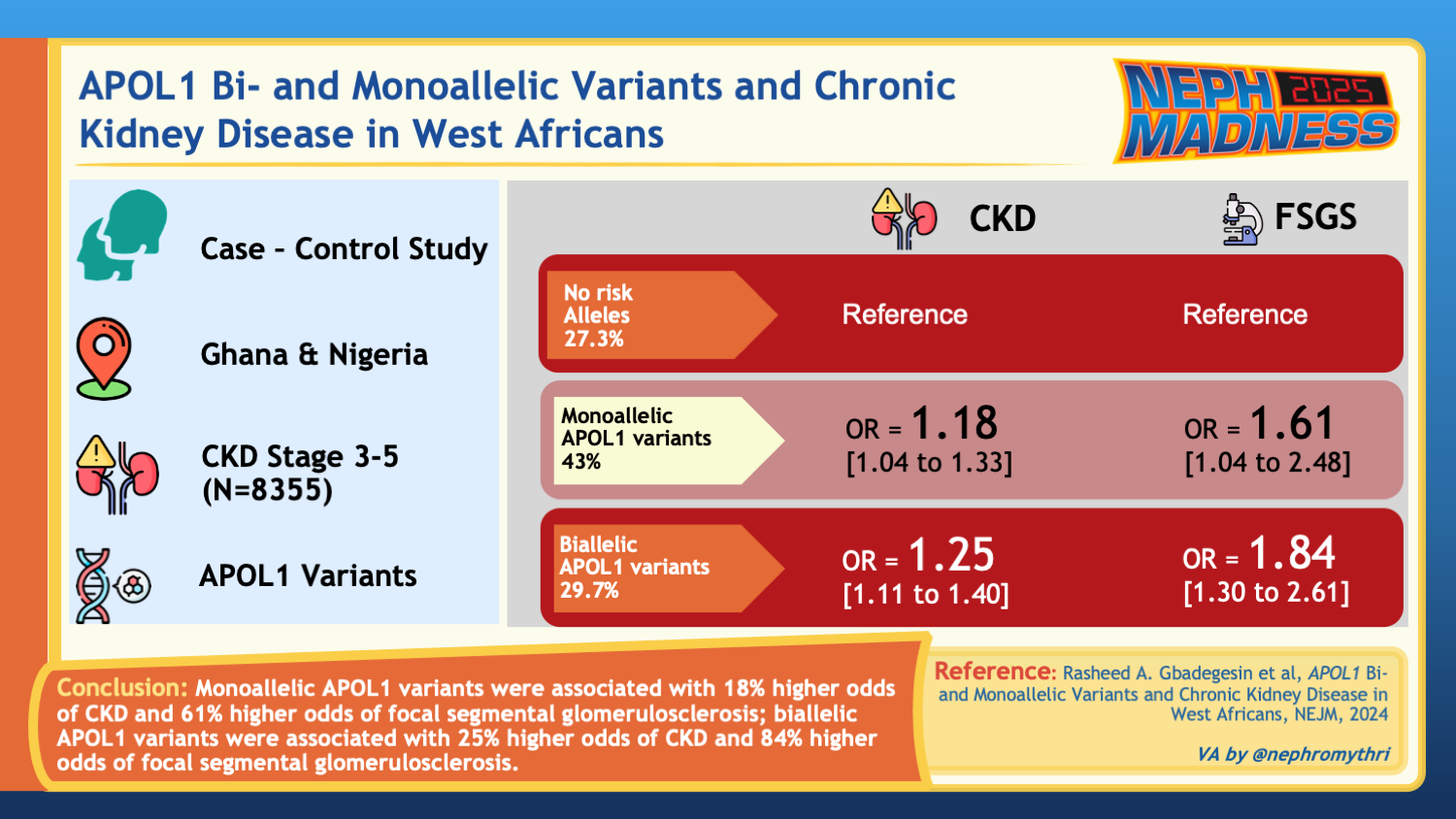

The APOL1 gene encodes apolipoprotein L1, which plays a role in innate immunity by providing protection against Trypanosoma brucei, the parasite responsible for African sleeping sickness. Two major risk alleles (G1 and G2) in the APOL1 gene have been linked to increased risk for FSGS. Traditionally, it was thought that carrying only one risk allele did not significantly elevate the risk of kidney disease; instead, the presence of two alleles (in combinations such as G1/G1, G1/G2, or G2/G2) was considered necessary to confer substantial risk. However, recent research suggests that individuals with a single APOL1 risk allele may also experience an elevated risk of kidney disease, although this risk remains lower than that observed in those with two risk alleles. You may be surprised to know that 35% of Black Americans have one risk allele, while 14% have two risk alleles; however, this is not enough to develop the disease. APOL1 variants are postulated to cause kidney disease via increased susceptibility to podocyte apoptosis and dysfunction after a secondary factor or “second hit” such as viral infection, obesity, or other trigger, which can lead to kidney injury in genetically predisposed individuals.

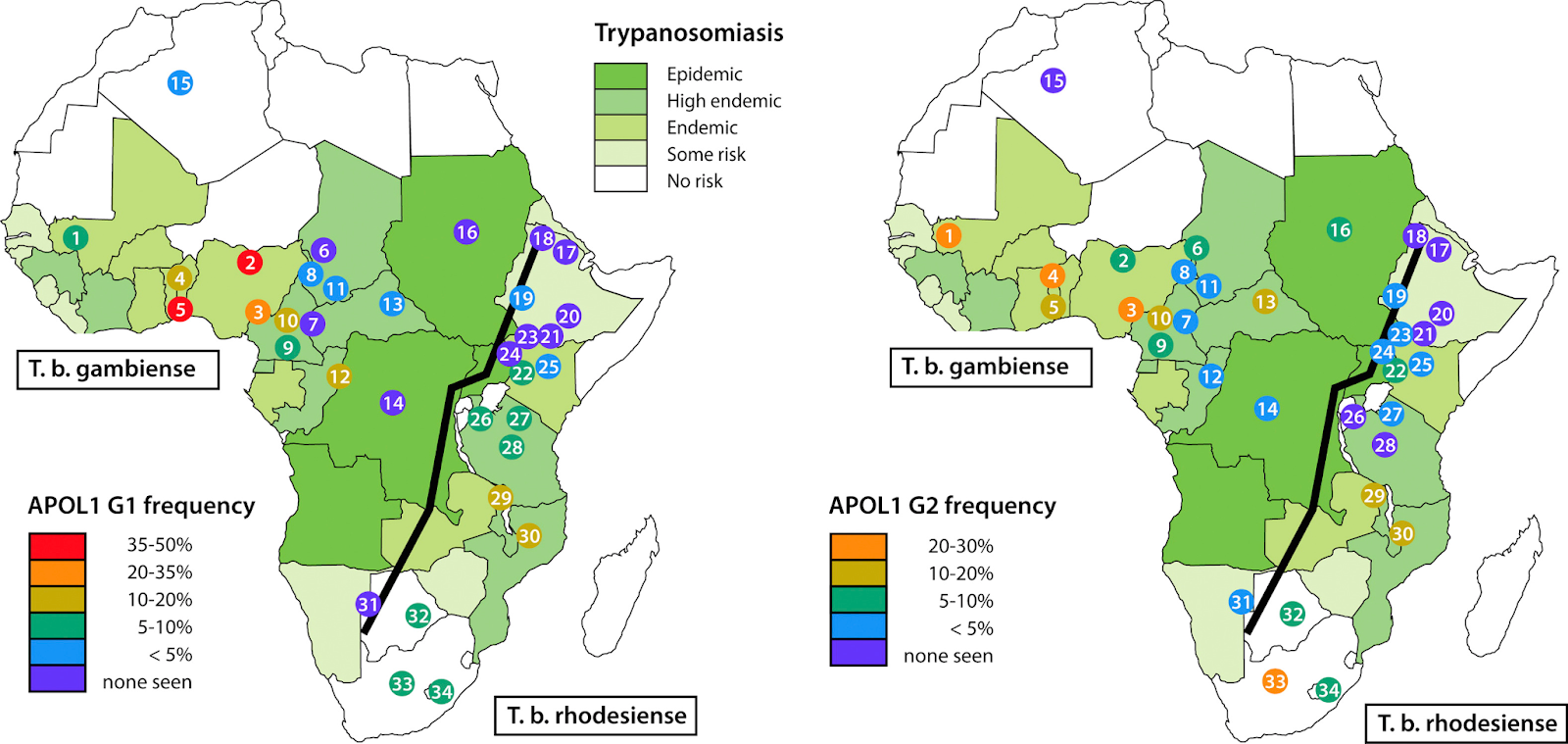

Geographic distribution of apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) renal-risk alleles and Trypanosoma brucei subspecies. Shown are the distributions of (left) G1 and (right) G2 alleles among population groups, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa, together with the population ranges for T brucei gambiense and T brucei rhodesiense (ranges based on information from World Health Organization). The Great Rift Valley is shown as a line running from southwest to northeast. Fig 1 from Freedman et al, © National Kidney Foundation.

Advances in drug development highlight the importance of making a genetic diagnosis, particularly for conditions like APOL1-mediated kidney disease. Identifying the genetic basis allows for targeting the underlying pathophysiology more precisely, as seen with inaxaplin (VX-147), an inhibitor of the APOL1 channel currently in phase 3 clinical trials. In a phase 2a clinical study of participants with two APOL1 variants and biopsy-proven FSGS with proteinuria, inaxaplin led to a 47.6% reduction in proteinuria, making it a potential treatment option for individuals with high-risk APOL1 genotypes.

When to pursue genetic testing

Genetic testing should be considered in individuals with early-onset FSGS, chronic glomerular hematuria, or proteinuria, particularly when accompanied by extra-renal manifestations, such as visual or hearing anomalies as often seen in collagen-related disorders. Although family history can be a key factor in recommending testing, it is often incompletely known or only becomes apparent after genetic testing reveals a hereditary basis. This is partly due to the incomplete penetrance of many monogenic disorders or the need for a secondary ‘hit,’ as seen in APOL1-associated kidney disease. In these cases, affected family members may only seek medical care after developing proteinuria, which retrospectively highlights the genetic underpinnings within the family. Additionally, patients with steroid-resistant forms of FSGS or FSGS of unknown cause are often associated with underlying genetic mutations and thus should undergo testing. As genetic testing becomes more commercially available and economical, the threshold for testing will continue to diminish.

Purpose and implications of genetic testing

Genetic testing in patients with an FSGS pattern of kidney disease offers multiple clinical benefits. It can guide treatment decisions by revealing diagnoses responsive to specific therapies (such as CoQ10 supplementation in patients with pathogenic variants of the COQ2, COQ6, or COQ8B genes) or by helping to avoid ineffective treatments like immunosuppression. It can prevent the need for invasive diagnostics such as a kidney biopsy in high-risk patients. Additionally, genetic testing aids in prognostication by providing insight into the disease course while also uncovering potential extrarenal manifestations that might otherwise go undiagnosed until later stages. Knowing the genetic cause can reduce patient and family anxiety by providing clarity, which may enhance patient engagement in their care. For instance, APOL1 carriers with awareness of their status achieved better blood pressure control. On a broader scale, genetic testing advances our understanding of FSGS pathogenesis and supports the development of targeted therapies by increasing the pool of genetically characterized patients for research. The identification of genetic causes of FSGS pattern of injury has significant implications for kidney transplantation. Recurrence rates of FSGS in the transplanted kidney are lower in patients with genetic forms of the disease. Moreover, genetic results can inform family members about their risk of developing FSGS, allowing for early detection, targeted therapy, or closer monitoring if genetic risk factors are present.

COMMENTARY BY NORA FRANCESCHINI:

But First, Think Genetics

In this podcast episode of GN in Ten hosts hosts Koyal Jain and Kenar Jhaveri are joined by Elena Cervantes, Jordan Nestor, and Matt Gross:

Episode 8: NephMadness 2025 Genetics Region

Team 2: Genetic Counseling

Copyright: bbuilder / Shutterstock

“Whoa, this is heavy.” Once you’ve hit 88 mph and ordered genetic testing, reviewing the results can feel like stepping out of the DeLorean into the unknown. Variants of uncertain significance, insurance implications, and the question of whether to test relatives—these are just a few challenges you’ll encounter in the future of genetics and kidney disease care.

Genetic counseling is more than just interpreting results; it’s about navigating complex discussions on risk, implications for family, and the potential for unintended discoveries. Preparing patients and their families for what to expect (and how to process the unknown) is as essential as making the diagnosis itself. Just like Marty and Doc faced unexpected twists, our role is to guide patients through these twists in the genetic landscape, helping them understand the journey ahead and manage any unexpected outcomes.

Purpose of genetic testing

Genetic testing is increasingly used for the evaluation of suspected genetic kidney disease. A multicenter study conducted in Ireland identified a genetic cause of CKD in up to 37% of patients, most of which had a family history of kidney disease or extrarenal manifestations. And just like Marty McFly’s skateboarding skills evolve, our genetic insights may soon lead to tailored treatments: APOL1-related kidney disease could potentially be managed with drugs such as inaxaplin (VX147). A post-hoc analysis of the DUPLEX trial demonstrated a more pronounced proteinuria reduction in patients with genetic FSGS treated with sparsentan compared to irbesartan. Identifying mutations in potential kidney donors can help evaluate the risk of developing kidney disease after transplantation for both donors and recipients. Finally, when a genetic mutation is identified in a relative, at-risk family members may consider genetic testing to determine whether they carry the pathogenic variant.

Testing modalities

Diagnostic yield depends on the type of genetic variants being assessed and the selection of the testing method.

Sanger sequencing

Sanger sequencing is a highly accurate method designed to detect single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions or deletions (INDELs) within a specific gene or targeted region. It relies on the incorporation of fluorophore-labeled dideoxynucleotide (ddNTPs) which lack a 3’ hydroxyl group. As these ddNTPs are incorporated, they cause termination of DNA synthesis at specific bases, generating DNA fragments of varying lengths. Reiteration of primer annealing and DNA extension cycles results in fragments with the fluorophore labeled ddNTPs at each position. The fragments are then separated by capillary electrophoresis and the sequence is deduced based on the fluorescently labeled terminators. Although its role in large-scale sequencing has diminished with the rise of next generation sequencing (NGS), it remains a valuable tool for targeted applications, such as testing a specific gene in at-risk family members, confirming variants detected by NGS, or sequencing genes that are technically difficult to analyze with NGS.

Curated gene panels/targeted next generation sequencing

NGS, also referred to as massively parallel sequencing, is like the flux capacitor of modern genomics—powering rapid advances that allow us to sequence millions of DNA fragments simultaneously in parallel. Compared to the “slow and steady” days of Sanger sequencing, NGS offers lightning-fast sequencing with a massive data output, all at a fraction of the cost. Curated gene panels or targeted-NGS are our go-to tools in clinical practice. These panels are designed to assess a specific set of genes known to be associated with kidney disease. The process involves fragmenting DNA into short segments, enriching the regions of interest using probe-based hybridization or PCR amplification, and preparing a sequencing library by adding adapters and unique sample identifiers. The prepared DNA is then sequenced in parallel. Bioinformatic tools align these sequences to a reference genome to identify genetic variants, which are then analyzed for clinical relevance. Just like dialing in a specific year in the DeLorean, these panels—offered by companies like Invitae, Blueprint Genetics, GeneDx, Natera, and Fulgent Genetics—focus on what’s most relevant and cost-effective for nephrology and other specialties.

Whole exome sequencing (WES)

WES takes the next leap via NGS technique by sequencing the entire exome, which is the part of the genome composed of exons—the coding regions of the genes that make up about 1-2% of the genome but contain most known disease-related variants. WES is often used in research settings or in patients for whom gene panel testing has not provided a diagnosis. WES may yield results in cases where a curated panel is negative, but its broader nature means a higher likelihood of finding variants of uncertain significance (VUS). Often, WES is not typically a “standard” orderable test in a general clinical setting and would require a researcher interested in conducting this type of sequencing.

Other options

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) is the comprehensive “full future-view,” examining every part of the genome, though its use is less common in clinical nephrology due to cost and technical challenges. Meanwhile, chromosomal microarray (CMA) testing is a high-resolution genetic diagnostic tool used to detect chromosomal abnormalities, such as copy number variations (CNVs), making it the test of choice for structural variant detection, particularly in individuals with developmental disorders, including congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract.

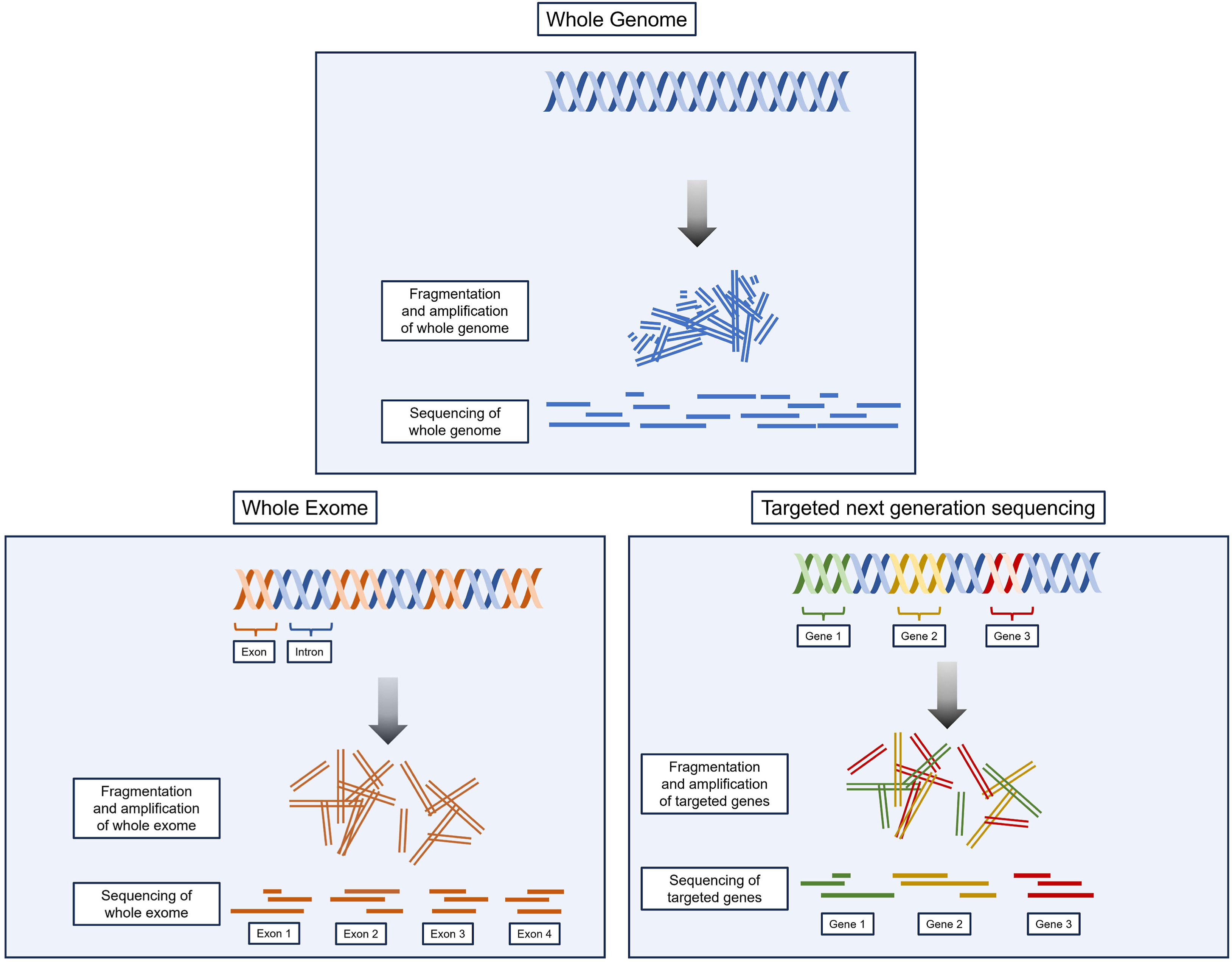

Comparison between WGS, WES, and t-NGS. WGS, as the name implies, includes sequencing of the entire genome. WES sequences all exons, the approximately 1% of the genome-encoding proteins. With t-NGS, the exons of a precurated list of genes are sequenced. For most cases, t-NGS will be sufficient; however, if t-NGS is negative and the suspicion of a genetic disorder is higher, WES or WGS can be considered. Fig 3 from Aron and Dahl, © National Kidney Foundation.

Ensuring Informed Consent

Informed consent is a critical part of genetic counseling and testing. It involves helping the patient understand the medical, financial, psychological, and familial implications of test results. It should be noted that in addition to in-person counseling, some states require written informed consent. With the increasing use of next-generation sequencing, the availability of such expansive genomic data has introduced new challenges to the traditional concept of informed consent. These challenges include whether it is even feasible to meet previously accepted standards of informed consent for tests with far-reaching implications. Below are key elements of the informed consent process, including areas where difficulties have been commonly reported.

Results and treatment expectations

Patients should be made aware of the possible outcomes of genetic testing, including findings that may or may not change clinical management. In some cases, a genetic diagnosis may lead to additional tests or specific treatment changes, while in others, patients may face negative or inconclusive results.

Costs

Insurance coverage varies depending on the specific test and patient scenario. Most genetic testing companies will help you verify coverage by submitting a pre-authorization request to the patient’s insurance. If the patient prefers to pay out-of-pocket or if insurance denies coverage, most companies have fixed self-pay rates or financial assistance based on income.

Risk of discrimination

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) provides some protection against discrimination based on genetic information for health insurance and employment. Under GINA, health insurers cannot use genetic test results or family medical history to determine eligibility, premiums, or coverage decisions. Similarly, employers with 15 or more employees are prohibited from using genetic information in hiring, firing, job assignments, or promotions. However, GINA does not extend to other forms of insurance such as disability, life, or long-term care insurance. Insurers in these domains may use this information to deny coverage or increase premiums, and thus patients should be counseled on the potential implications of testing, particularly if they are considering purchasing these types of insurance in the future. Furthermore, GINA does not extend to members of the military where genetic information may be utilized to influence career assignments or determine eligibility for certain benefits.

Kidney donation

Genetic testing is becoming a key step in evaluating potential living kidney donors. When genetic variants are found, it is crucial to consider the penetrance of the disease and what level of risk the donor and the transplant team are willing to accept. For instance, in individuals with ADPKD due to PKD1 or PKD2 mutations, the lifetime risk of developing kidney cysts and associated complications is fully penetrant (i.e.100%), though dependent on age. APOL1 genetic variants in potential donors represent a particularly complex issue in living kidney donation – with an ethical debate balancing the autonomy of the potential donor, who may wish to donate to a loved one despite the risks, with the responsibility of transplant teams to ensure donor safety and minimize harm. The APOLLO study, an ongoing research effort, aims to further clarify the implications of APOL1 status in donors and recipients.

Genetic counselors

Genetic counselors are healthcare professionals with specialized expertise in genetics and counseling. Their role includes preparing patients for a range of possible outcomes, from identifying pathogenic variants to finding VUS. They also provide guidance on how specific results could affect medical management, potential risks to family members, and decisions around cascade testing for relatives. Genetic counselors are trained to address the psychological and social impacts of testing, including managing anxiety, guilt, or concerns around genetic discrimination, and can offer coping strategies for dealing with these issues.

Importantly, many genetic testing companies offer complimentary access to genetic counseling services, allowing patients to work with a counselor through virtual or phone consultations even if they do not have local access to these resources. This service helps ensure that patients fully understand the risks, benefits, and limitations of testing, fostering informed decision-making and providing support for patients navigating complex genetic information.

Return of results challenges

Secondary findings

Secondary findings refer to clinically significant genetic results discovered incidentally during genetic testing, unrelated to the primary reason for the test. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) provides a list of genes where secondary findings should be considered for reporting, such as hereditary cancer syndromes or cardiovascular disorders where early interventions can improve clinical outcomes. Whether secondary findings are reported depends on the specific company, the type of test being performed, and patient consent.

Variants of uncertain significance

Genetic test results are classified using a standardized scheme based on the likelihood that a variant is disease-causing. Variants classified as pathogenic (P) or likely pathogenic (LP) are expected to impair gene function, leading to disease. However, for many variants, the available evidence is insufficient or conflicting, preventing a clear association with disease. These are classified as VUS and should not be used to assign risk or guide medical management. Patients must be counseled on the relatively common possibility of finding VUS. Importantly, most VUS will eventually be reclassified as benign.

Psychosocial consequences

Psychosocial consequences of genetic testing include anxiety, guilt, and potential impact on family dynamics. For example, a patient may feel guilty that a gene variant she carries could have been passed to her children. Alternatively, genetic results may cause tension or disagreements among relatives about whether to pursue testing or how to handle the information. Access to genetic counseling services can help patients and families navigate these challenges effectively.

Testing relatives of positive patients

Testing family members – known as cascade testing – involves testing at-risk relatives after a disease-causing variant is identified in a proband. It is considered standard practice in clinical genetics and is endorsed by kidney health organizations. However, testing children raises ethical and psychosocial questions. There are concerns around the child’s autonomy, there is risk for genetic discrimination in insurance and employment (particularly relevant in conditions with incomplete penetrance or variable age of onset), and it can negatively impact family dynamics leading to issues such as misattributed paternity. Genetic testing in children is typically recommended only if a positive result would have immediate clinical implications. In some cases, testing other adult family members, such as the child’s other parent or the patient’s parents, can help clarify the pattern of penetrance and the likelihood that the child inherited the mutation.

– Executive Team Members for this region: Elena Cervantes @Elena_Cervants and Matt Sparks @Nephro_Sparks – @nephrosparks.bsky.social | Meet the Gamemakers

How to Claim CME and MOC

US-based physicians can earn 1.0 CME credit and 1.0 MOC per region through NKF PERC (detailed instructions here). The CME and MOC activity will expire on June 1, 2025.

Leave a Reply