#NephMadness 2025: Minimal Change Disease Region

Submit your picks! | @NephMadness | @nephmadness.bsky.social | NephMadness 2025

Selection Committee Member: Susan Samuel @drsusansamuel

Susan Samuel is a Clinician Scientist and Pediatric Nephrologist at the BC Children’s Hospital, in Vancouver, Canada. She received her undergraduate medical degree from the University of British Columbia, completed her postgraduate medical training in pediatrics and nephrology at SickKids Hospital in Toronto, and completed her MSc degree with specialization in Clinical Epidemiology at the University of Toronto. Her research goals are to improve care and outcomes of children with kidney disease and kidney failure. She leads the multi-centre Canadian Childhood Nephrotic Syndrome Project, a multi-centre initiative to improve care of children with nephrotic syndrome. She is passionate about mentoring and training individuals to pursue careers in health research, and serves as the Director of the ENRICH program.

Writer: Mallory Downie @mallorydownie

Mallory Downie is an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics in the Division of Nephrology at McGill University and Junior Scientist at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre. She has trained in genetics, pediatrics, and nephrology. She is currently the principal investigator of a bioinformatics lab working to identify new genes and genetic risk factors in childhood kidney disease.

Writer: Robert Myette @RobertMyette

Robert Myette is a pediatric nephrologist-scientist pursuing fundamental and translational basic science research work at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute. His work is targeted at understanding the molecular underpinnings of pediatric nephrotic syndrome.

Competitors for the Minimal Change Disease Region

Team 1: Minimal Change Disease Diagnosis and Pathogenesis

versus

Team 2: Minimal Change Disease Relapse

Image generated by Evan Zeitler using DALLE-E 3, accessed via ChatGPT at http://chat.openai.com, February 2025. After using the tool to generate the image, Zeitler and the NephMadness Executive Team reviewed and take full responsibility for the final graphic image.

Team 1: Minimal Change Disease Diagnosis and Pathogenesis

Copyright: Mateusz Lachowski Photo / Shutterstock

Introduction

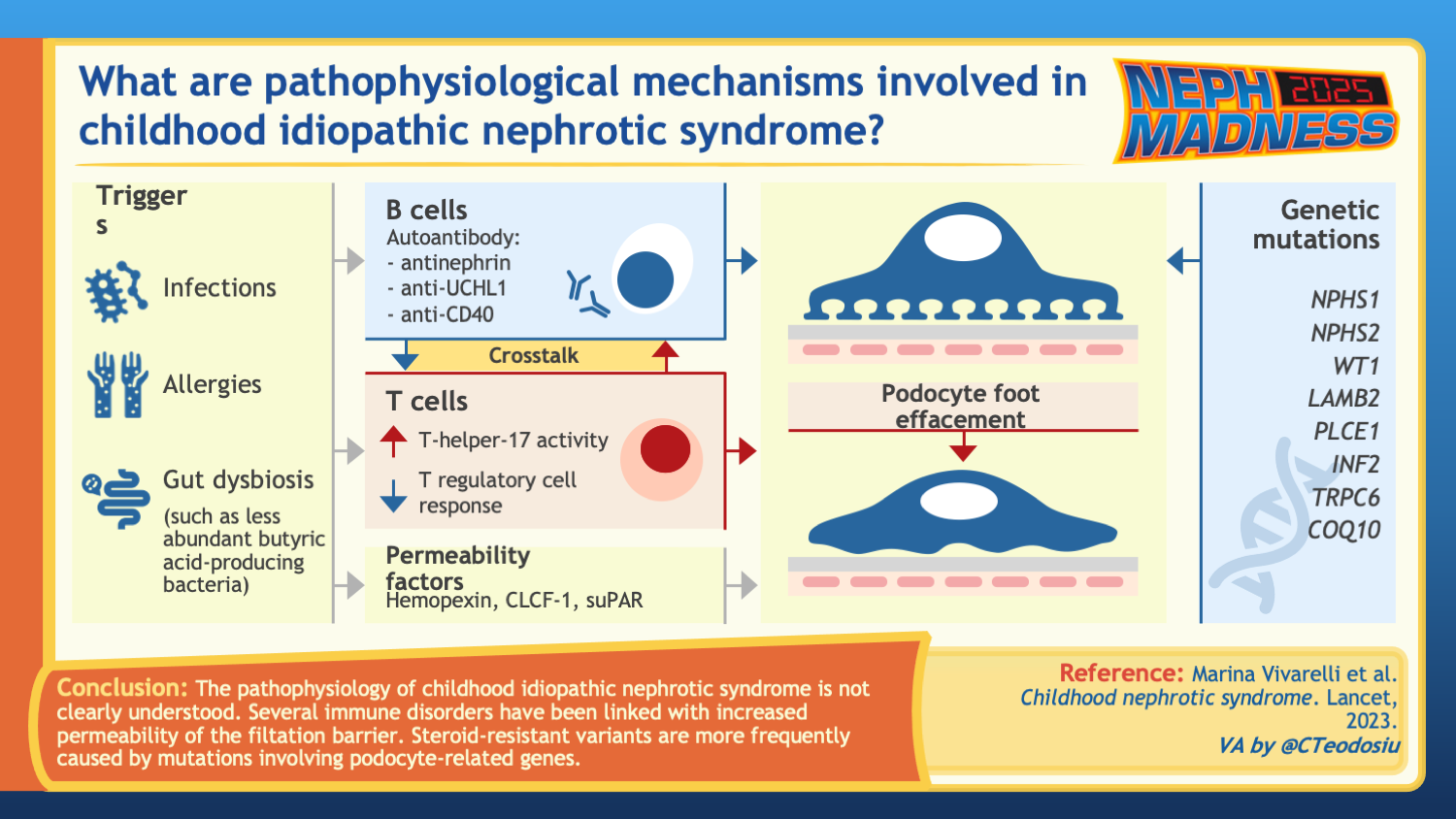

Minimal change disease (MCD) is characterized by injury to podocytes and features massive proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and edema. Though MCD is diagnosed by kidney biopsy in adults, children with steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome (SSNS) are infrequently biopsied because they are presumed to have MCD; thus, MCD and SSNS are often considered synonymous. The pathogenesis of MCD/SSNS is yet unknown.

Childhood nephrotic syndrome is the most common glomerulopathy in children, and its clinical classification is primarily based on the response to glucocorticoid treatment within the first year following diagnosis. SSNS is defined as complete remission after four weeks of treatment with the recommended dose of steroids. Patients are classified as infrequent relapsers if they experience fewer than two relapses within six months or fewer than four relapses within twelve months. Frequent relapsing nephrotic syndrome (FRNS) are those with more than two relapses within six months or greater than or equal to three relapses within twelve months. Steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome (SDNS) is characterized by two consecutive relapses while on glucocorticoid therapy or within 14 days of discontinuing glucocorticoid treatment. Patients who fail to achieve complete remission after four weeks of the recommended glucocorticoid dose are classified as steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS).

MCD is a puzzling disease. The disease shows no apparent sign of inflammation in the kidney, yet MCD responds to immunosuppressive drugs such as corticosteroids, strongly suggesting an immune pathogenesis. Moreover, the onset of the disease is typically associated with an environmental exposure to another immune-activating process, such as infection, vaccination, allergy, systemic autoimmunity, or cancer. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in MCD and SSNS also show the strongest genetic risk loci to be at the human leukocyte antigen (HLA), which encodes cell-surface proteins responsible for regulation of the immune system. For more than 30 years, MCD was considered a T cell-mediated process in that T cells were thought to secrete a circulating permeability factor that injured the podocytes. However, this circulating factor has never been identified. Evidence from the last several years points more and more toward the role of B cells and auto-antibody formation in the pathogenesis of the disease.

B cells in MCD

A potential role of B cells in the pathobiology of MCD first emerged due to the therapeutic effect of B cell-depleting anti-CD20 antibodies (rituximab, ofatumumab, and most recently, obinutuzumab) in inducing and maintaining remission in children with SSNS. Moreover, the association of MCD occurrence with non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphoma where tumor cells derive from mature B cells, and with Epstein Barr Virus infection (EBV), which mainly targets B cells, provides further compelling evidence. The role of B cells in the pathophysiology of MCD was recently substantiated with the discovery of anti-nephrin antibodies in children and adults with active MCD and atypical B cells in children with active SSNS.

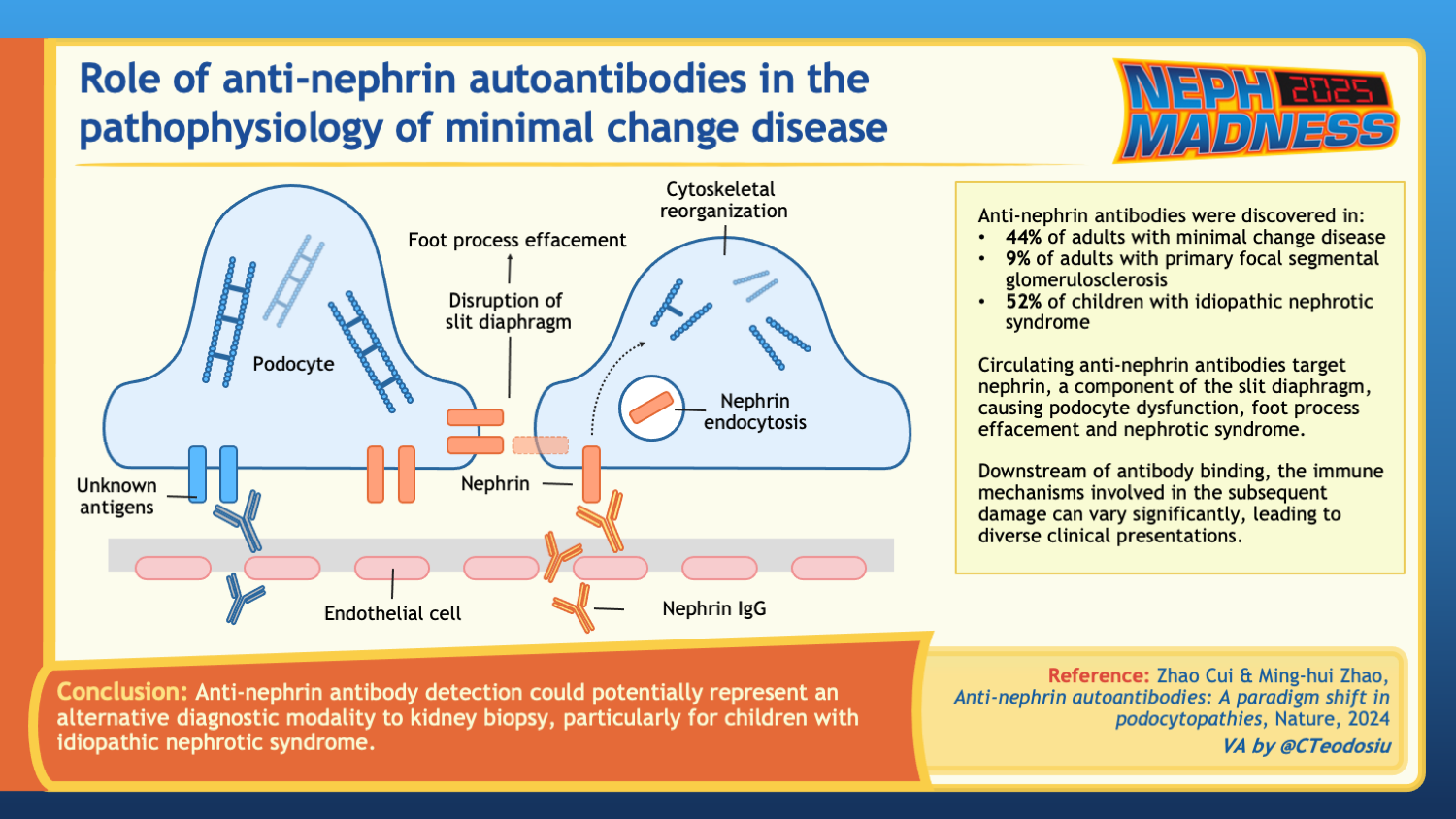

Anti-nephrin antibodies

Nephrin is an important component of the slit diaphragm, the specialized cell junctions between mature podocytes and the site of injury in MCD. Rare monogenic mutations (minor allele frequency <1%) in NPHS1, that cause lack of nephrin localization to the cell surface, cause what is termed Finnish type congenital nephrotic syndrome, and common genetic variants (minor allele frequency >1%) in NPHS1 have more recently been associated with SSNS in genome-wide association studies. In a recent study by Watts et al, authors used a custom-developed indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to demonstrate that 18 of 62 (29%) of patients with MCD and active disease had anti-nephrin antibodies in their serum. Interestingly, anti-nephrin antibodies were reduced or completely absent in patients with MCD during complete or partial remission. The authors also identified IgG colocalizing with nephrin, which they speculated to represent in situ nephrin antibody binding in patients with circulating anti-nephrin antibodies.

These results were expanded across other podocytopathies and centers in a more recent study by Hengel et al, which found anti-nephrin antibodies in 46 of 105 (44%) of adults with MCD and 94 of 182 (52%) of children with SSNS. Antibody measurements were as high as 69% and 90% in adults and children, respectively, who had active disease, some on no immunosuppression, therefore correlating with disease activity. Anti-nephrin antibodies were either absent or found in much smaller proportions of patients with other immune-mediated glomerulopathies.

Overall, the possibility of anti-nephrin antibodies as a novel glomerular biomarker for a subset of MCD is very promising and may pave the way for use of anti-nephrin antibodies, not only for diagnosis of MCD but also as a potential marker of response to therapy or for predicting an impending relapse or recurrence post-transplantation – much like is done with anti-PLA2R antibodies in membranous nephropathy.

Atypical B cells

B cells generate antibodies, like the anti-nephrin antibodies mentioned above. Building on the hypothesis that MCD is an autoimmune disease caused by antibodies, Al-Aubodah et al demonstrated a distinct B cell signature in children with active SSNS. Through the use of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), the authors demonstrated that the expansion of two specific B cell populations in the extrafollicular B cell pathway – atypical memory B cells (atBCs) and short-lived antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) – was evident in children with active disease. They further demonstrated that treatment of disease with corticosteroids and rituximab targeted these specific SSNS-associated B cell populations (ASCs only), with rituximab providing more specific and extensive coverage. This work provides further support in the use and development of B cell-targeting therapies in the treatment of SSNS/MCD. Moreover, the future investigation of ASCs as biomarkers for disease activity is also very promising.

Summary

Taken together, the discovery of anti-nephrin antibodies and the characterization of the distinct B cell signature of active MCD and SSNS confirms that B cells play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. These discoveries provide valuable insight into the etiology of a disease that has been poorly understood for decades. These findings provide a mechanistic rationale for further development of B cell-targeted therapies and for further characterization of these potential biomarkers in predicting disease activity and treatment response.

In this episode of The Kidney Chronicles, host Emily Zangla is joined by NephMadness Exec Ana Catalina Alvarez-Elías and pediatric nephrologist Mallory Downie:

Episode 36: NephMadness 2025 Minimal Change Disease in Kids

Team 2: Minimal Change Disease Relapse

Copyright: Tanasan Sungkaew / Shutterstock

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is a podocytopathy characterized by proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and edema. Podocyte effacement on histology is a unifying feature. Both pediatric and adult patients with MCD are treated initially with steroids with escalation to steroid-sparing, second-line agents as required. The approach to relapses also usually involves steroids.

Adult Nephrotic Syndrome

In adults, the approach to treatment during the initial episode of MCD includes high-dose oral steroids, usually prednisone, at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day, with a maximum dose of 80 mg for 4-16 weeks, followed by a taper [KDIGO 2021]. For those patients unable to tolerate steroids, steroid-sparing agents are offered and include cyclophosphamide, calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and B cell-depleting therapies such as rituximab [KDIGO 2021].

Steroid response is the cornerstone for both the prognosis of the disease and its clinical classification. Recently, the Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network (NEPTUNE) externally validated a promising urinary biomarker risk ‘score’ which incorporates the following five biomarkers: vitamin D binding protein (VDB), fetuin-A (FetA), transthyretin (TTR), alpha-1 acid glycoprotein 2 (AGP2) and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL). The biomarker ‘score’ was measured in 34 adults with SSNS, and was compared to 24 patients with SRNS. The biomarker ‘score’ was able to predict development of steroid resistance with both a sensitivity and specificity of 0.74 and a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) area under the curve (AUC) of 0.79. Though this AUC implies that this biomarker score is not reliable enough to distinguish disease etiology in an individual patient, if other biomarkers (such as genetic variants or serological tests) become available to clinicians in the future, the clinical utility of this score might be re-examined.

Despite these advances, there is still no reliable biomarker available to determine initial steroid responsiveness or frequency of relapse after remission in adults. This is an important consideration given that relapses occur in approximately two-thirds of adults with MCD. Predictive factors for relapse include a younger age of onset, not initially using cyclophosphamide, and shorter glucocorticoid treatment duration. In the event of infrequent relapses of MCD, adults are typically treated with high-dose steroids, followed by rapid taper. For those with frequent relapses or steroid dependence, steroid-sparing therapies such as cyclophosphamide, tacrolimus, MMF, or rituximab are initiated. A study by Heybeli et al suggested that treatment with rituximab may increase the likelihood of discontinuing immunosuppressive agents. This finding contributed to the initiation of the TURING trial, a two-arm, randomized, placebo controlled, phase III clinical trial in the United Kingdom, currently recruiting, which assesses the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of rituximab. In patients who are steroid-resistant, second-line medications will also be trialed, with calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus being the preferred agents.

Pediatric Nephrotic Syndrome

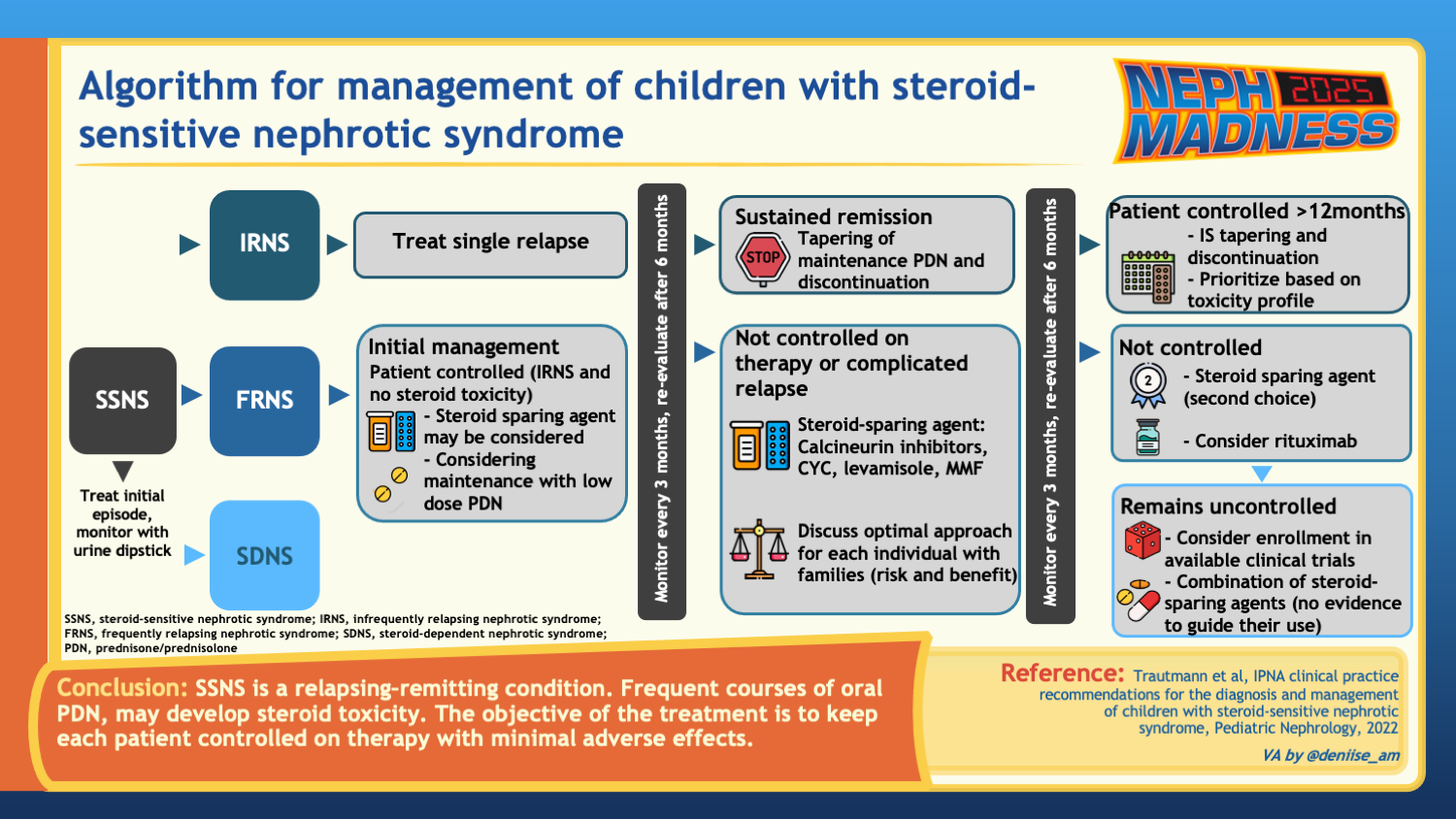

In children, the initial approach differs in that steroids are the first line agent in all cases. The current International Pediatric Nephrology Association (IPNA) and KDIGO guidelines recommend using 60 mg/m2/day or 2 mg/kg/day for 4-6 weeks (with a maximum dose of 60 mg/day) and 40 mg/m2/ every other day or 1.5 mg/kg/ every other day for 4-6 weeks, for a total duration of 8-12 weeks for initial treatment (2022 IPNA SSNS Guidelines). Overall, recent trials showed no significant benefit in prolonging treatment past 12 weeks with respect to delaying time to first relapse and reducing relapse frequency. Though the older guidelines recommended a longer steroid taper, longer duration and higher cumulative exposure to steroids do not provide significant benefit.

Because the pathophysiology of childhood NS is unclear, clinicians often provide prognostic information based on the response to steroid treatment. Using response as a metric helps guide classification, and sometimes clinical decision-making for subsequent treatments including the use of glucocorticoid-sparing agents. Knowledge gaps in the underlying pathogenesis of disease creates variability in clinical practice where clinicians – together with patients and caregivers – choose which steroid-sparing drug may work best in order to reduce relapse frequency and/or maintain remission.

Genome-wide association studies have revealed nine genetic risk loci associated with the development of SSNS in children. Each study found the strongest genetic risk locus to be at the HLA (which encodes the proteins of the human immune system). In these studies, there are observed ancestral differences in the genetic risk variants for SSNS among South Asian, East Asian, African, and European children, particularly at the HLA locus. In African populations, APOL1 was found to be specifically associated with SRNS. Urinary biomarkers have also been extensively investigated. For example, a proteomic study comparing pediatric patients with SSNS and SRNS over a two-year follow up period demonstrated that a urine panel including ten different urinary biomarkers predicted steroid resistance more effectively than a single biomarker with a ROC AUC of 0.92.

Up to 80% of children with initially steroid-responsive NS will experience relapse. Furthermore, 30-50% will have frequent relapses or become steroid-dependent. The risk for relapse persists even after transitioning from childhood to adulthood. A large population-based study conducted in Israel using health administrative data found that the average age at which children reached long-standing remission was 11 years (411/524 patients). A significant proportion of participants (22%) continued to experience relapse once they reached adulthood (113/524 patients).

Predictive factors for relapse in pediatric patients

Clinical characteristics and common laboratory biomarkers have been described as potential predictors of prognosis, including younger age at presentation, time to relapse, infections, increased dyslipidemia, microhematuria, and lower albumin levels. However, to date, there are no reliable predictive markers for relapse in children. Specifically, demographic factors, kidney histology, and the presence of initial steroid sensitivity are not useful in predicting relapse rates or the likelihood of long-term remission. The relapse rate varies by ancestry. For instance, children of East/Southeast Asian ancestry exhibit up to six times higher incidence of NS compared to those of European ancestry. Nevertheless, children of East/Southeast Asian ancestry have a lower rate of relapse than children of European descent.

Substantial efforts are underway to identify a non-invasive, dependable, measurable predictor of relapses. It is currently debated whether MCD and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) are a continuum of the same immune-mediated disease. Given this, we have been able to apply evidence from FSGS research to MCD, as it pertains to the elusive circulating factor. First hypothesized by Gentil et al many years ago, a serum ‘factor’ was thought to play a role in relapse. This hypothesis is supported by evidence from animal models, which show proteinuria when rats are exposed to plasma from patients with NS. Further, case reports of women with FSGS showing increased fetal kidney echogenicity have suggested transplacental exposure of the circulating factor from the mother to the fetus. Perhaps the most convincing insights were from isolated cases reporting the need for kidney allograft removal due to massive proteinuria recurrence and severe kidney function decline in patients with FSGS. Subsequently, there was recovery of kidney function after re-transplanting the allograft to a patient without FSGS. Given the evidence around a presumed circulating factor, many studies are now trying to determine if biomarkers in the serum or urine can be identified as the circulating factor, or at least as a mechanism to predict relapse.

Several urinary biomarkers have been studied in the past in both adults and children, and some of them have shown promising performance as markers of steroid sensitivity, including VDBP, NGAL, alpha 1-B glycoprotein (A1BG), and CD80 (also known as B7-1). However, these biomarkers have not been studied in terms of relapse prediction. Regarding serum biomarkers, hemopexin has been studied as a putative circulating factor and marker of relapse. More recently, anti-nephrin antibodies have been identified in the serum during relapse (as discussed by Team 1), and might represent both a biomarker of relapse, as well as the circulating factor in some cases of MCD.

Relapse treatment in pediatrics

The approach to relapse includes treating again with prednisone 60 mg/m2 daily (maximum 60 mg/day) until the urine is negative for 3 days consecutively. Thereafter, 40 mg/m2/every other day for 4 weeks is prescribed, and then stopped. Importantly, there was a historic treatment approach to preventing relapse by giving low dose prednisone to children with NS who were experiencing an upper respiratory tract infection (URTI). The PREDNOS2 trial revealed that administering 6 days of daily low dose prednisone at the time of URTI did not reduce the risk of relapse. Though the 2021 KDIGO guidelines still recommend administering low dose prednisone during URTI, the up-to-date IPNA guidelines for managing children with steroid sensitive NS do not recommend the use of low-dose prednisone at the onset of upper respiratory tract infection; however, they do suggest considering a short course of low dose daily prednisone when children are already in a relapse and are on alternate-day steroids when challenged with an upper respiratory tract infection.

Currently, there is no conclusive evidence to help with selection of a second line agent in the context of steroid resistance or frequent relapse. Common strategies include attempting to switch to low dose alternate day prednisone, maintaining low dose daily prednisone, adding calcineurin inhibitors, cyclophosphamide, levamisole, MMF, and rituximab. The choice is made through shared decision making with the family, and/or patient, and balancing the risks and benefits while attempting to control the disease and minimize the exposure to prednisone. Ongoing research is dedicated to determining which agent would be best; however, no single clinical trial has yet compared all available options head to head.

In recent years, at least six clinical trials involving the pediatric population with NS have been published, proving some evidence on the efficacy of rituximab compared to either placebo or other steroid-sparing therapies. Although the interventional studies have been small, rituximab is increasingly used as a steroid-sparing agent in various clinical presentations of NS. This is based on the assumption that its effectiveness stems from its ability to deplete B cells. This trend has been most prominent in high-resourced countries where access to the drug is more readily available. However, from a global perspective, the cost and availability of medication significantly influences treatment decisions made by healthcare providers and families. One of the more affordable alternatives, although not available for human use in the United States or Canada (where its use is restricted to livestock), is levamisole. Levamisole, an antiparasitic agent listed on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Essential Medicines List, is widely used in the UK and Europe, as well as South American, African, and other low- and middle-income countries as a steroid-sparing option following relapse. A multicenter, international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted in patients with SSNS across five European countries and India found that, during the first 100 days post-diagnosis, the time to relapse was similar between the levamisole and placebo groups. However, the risk of relapse between days 100 and 365 (12 months) was 78% lower in the levamisole group (HR 0.22, 95%CI 0.11-0.43). A second non-inferiority trial showed that levamisole use in frequently relapsing NS resulted in a lower relapse frequency (22.5%) compared to prednisolone (40%). Both groups demonstrated similar rates of sustained remission, with levamisole showing a lower frequency of adverse events.

Conclusion

- The unresolved pathophysiology of MCD and SSNS presents significant challenges in identifying reliable biomarkers for predicting relapse risk, treatment response, and long-term prognosis.

- Ongoing investigations are focusing on various urinary and serum biomarkers linked to immune response pathways, and ancestry.

- The development of non-invasive tools to assist healthcare providers in clinical decision-making is crucial, particularly in the pediatric population.

- Relapses are primarily treated with steroids in pediatric patients, which increases the risk of adverse effects including delayed growth and bone health impairment.

- Numerous glucocorticoid-sparing therapies are currently being studied to identify the most effective treatment options based on clinical presentation, individual risk factors, and affordability of the drug.

- The KDIGO 2021 and IPNA guidelines offer robust and reliable recommendations to the international community, providing evidence-based treatment options. However, larger, multicenter, international randomized controlled trials comparing these therapies side by side are essential for refining treatment recommendations.

– Executive Team Members for this region: Ana Catalina Alvarez-Elías @catochita – @catochita.bsky.social and Matthew Sparks @Nephro_Sparks – @nephrosparks.bsky.social | Meet the Gamemakers

How to Claim CME and MOC

US-based physicians can earn 1.0 CME credit and 1.0 MOC per region through NKF PERC (detailed instructions here). The CME and MOC activity will expire on June 1, 2025.

Leave a Reply