#NephMadness 2025: Obesity in Kidney Transplant Region

Submit your picks! | @NephMadness | @nephmadness.bsky.social | NephMadness 2025

Selection Committee Member: Swee-Ling Levea @SweeLevea

Swee-Ling Levea is an Associate Professor of Medicine at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Living Donor Medical Director of the Kidney Transplant program. Her research focuses on metabolic syndrome in living kidney donors and the development of resources to optimize metabolic risk both before and after kidney donation. She is dedicated to patient education and advocates for multidisciplinary programs that support living donors at risk for metabolic syndrome with interest in incorporation of lifestyle modifications. Additionally, she is collaborating with the culinary medicine program at UT Southwestern to offer educational courses for living kidney donors, aiming to empower patients with lifestyle changes.

Selection Committee Member: Babak Orandi

Babak Orandi is an abdominal transplant surgeon and obesity medicine specialist at NYU Langone, where he is an associate professor of surgery and medicine. He trained at the University of Michigan, Johns Hopkins, UCSF, and Cornell, and has published >100 papers in top medical journals.

Writer: Alissa Ice

Alissa Ice is a second-year nephrology fellow at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, where she currently serves as a chief fellow. She completed her residency and chief year at Louisiana State University Internal Medicine Residency in Baton Rouge. Her interests include CKD, home modalities, renal physiology, and medical education.

Writer: Trevor Stevens

Trevor Stevens is a current second-year nephrology fellow and chief fellow at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. He completed medical school at the University of South Alabama and residency at Vanderbilt University Medical Center where he also served for a year as a chief resident. His interests are kidney transplantation and critical care.

Competitors for the Obesity in Kidney Transplant Region

Team 1: Obesity in Kidney Transplant Donors

versus

Team 2: Obesity in Kidney Transplant Recipients

Image generated by Evan Zeitler using DALLE-E 3, accessed via ChatGPT at http://chat.openai.com, February 2025. After using the tool to generate the image, Zeitler and the NephMadness Executive Team reviewed and take full responsibility for the final graphic image.

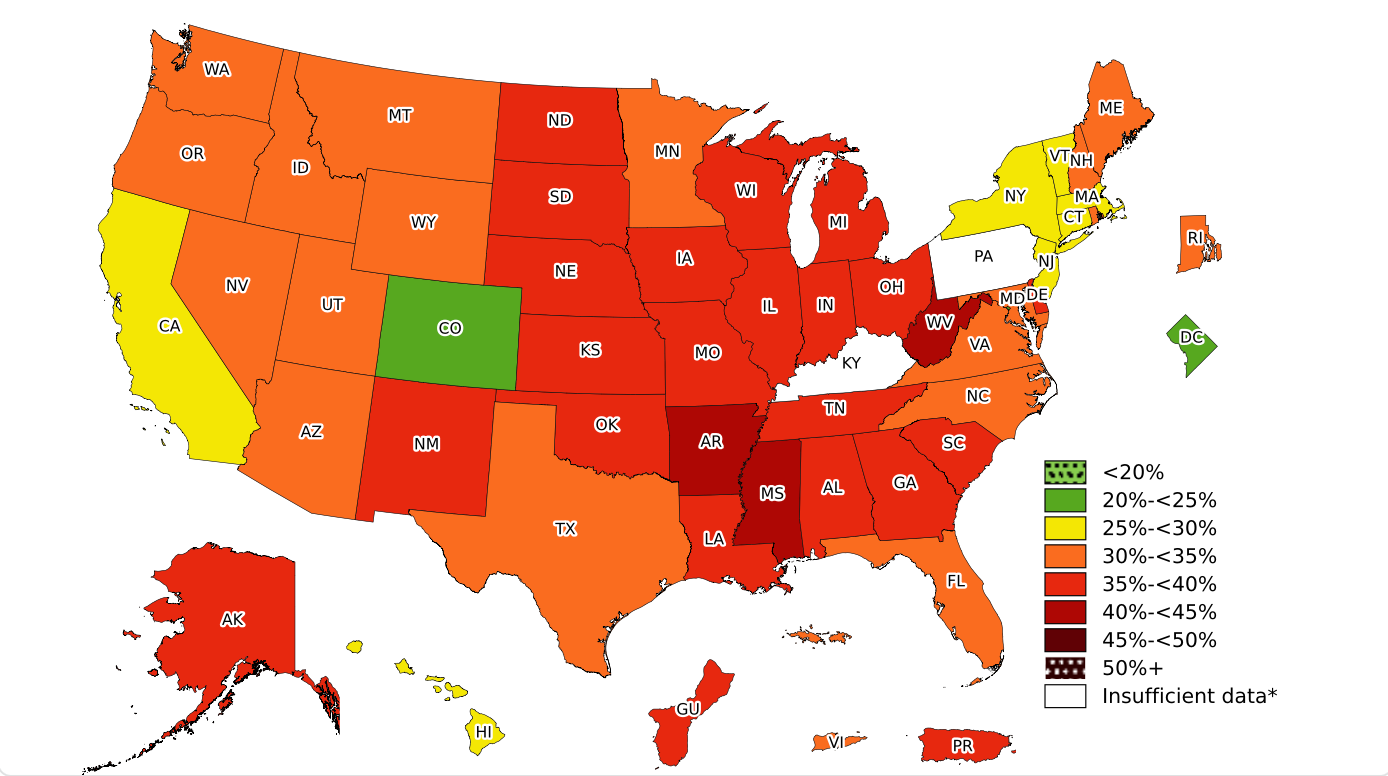

It is well known that obesity is rapidly becoming a significant public health problem. Both the World Health Organization and the Center for Disease Control define obesity as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2. The prevalence of obesity in the United States is 40%.

Adult Obesity Prevalence. From the CDC.

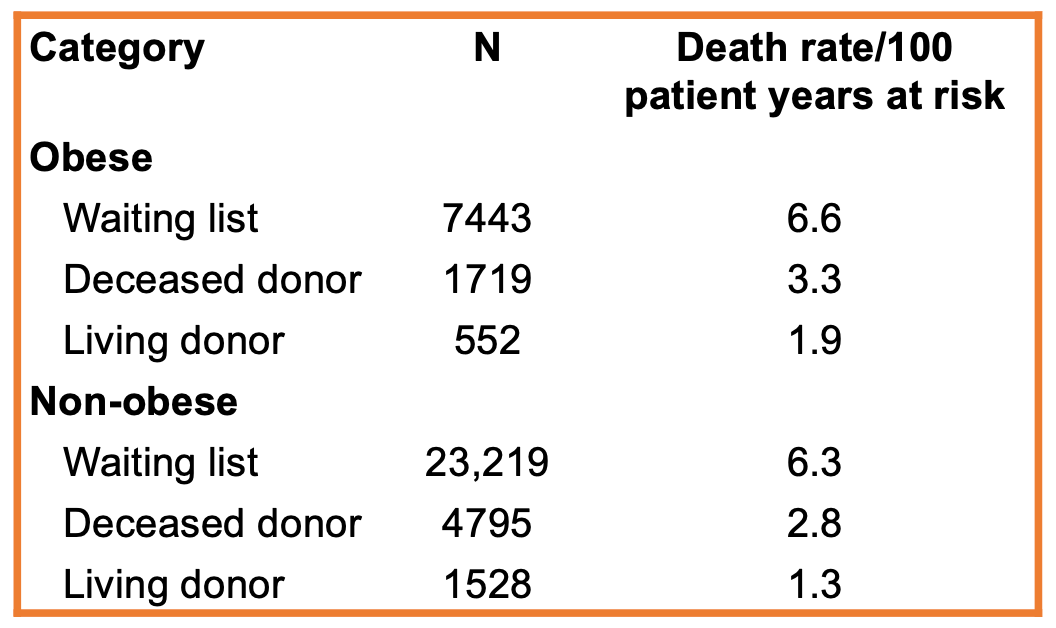

Obesity is also common in patients with kidney disease and at the time of kidney transplantation. In a cohort of 296,807 transplant recipients between 2000-2019, more than 30% of patients had a BMI ≥30 kg/m2, and there was a 48% increase in the number of recipients with a BMI >35 in between 2000-2004 and 2015-2019. Furthermore, upwards of 30% of patients post-transplant may gain over 10% of their baseline weight after the first year of transplantation. It is known that obesity has important implications in regards to post-kidney transplant outcomes, impacting surgical wound healing, cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, post-transplant diabetes mellitus (PTDM), and possibly immediate graft function. Obesity is also a barrier to kidney donation. While there is no universally accepted BMI cutoff among United States transplant centers for potential living kidney donors, most centers exclude donors based on obesity, using BMI cutoffs of 30 – 35 kg/m2. Despite these known issues, kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) with obesity have lower death rates than their transplant waitlisted counterparts with obesity who do not get transplanted.

As obesity, kidney disease, and kidney transplantation rates continue to increase, nephrologists will play a critical role in the overall health of our patients. We will increasingly be called upon to educate and deploy agents that impact both kidney disease and weight loss. We hope that by the end of this section, you will recognize the importance of kidney transplantation for the population with obesity and feel more comfortable addressing obesity in kidney transplantation, whether that be for the recipient or the donor. May The Biggest Loser™ of these two teams be the biggest winner!

Team 1: Obesity in Kidney Transplant Donors

Copyright: Kostikova Natalia / Shutterstock

With over 90,000 candidates on the kidney transplant waiting list in the United States, living donors are essential, affording recipients timely transplantation and improved outcomes. The aging population and rise in obesity have, not surprisingly, affected the living donor population, and although there has been a relaxation of the donor candidacy criteria, it remains challenging to balance obese donors’ safety and reasonable risk with their desire to donate.

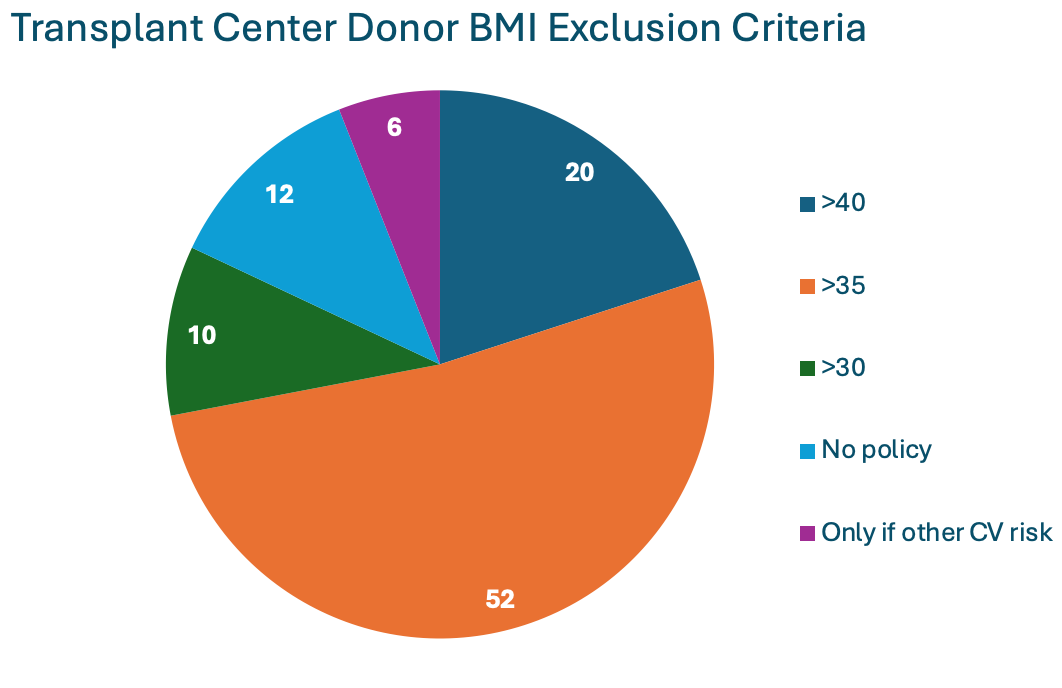

There is no standardized BMI threshold for donation. According to a 2007 United States transplant center survey, the majority of transplant centers excluded donors with a BMI >35 kg/m2.

Adapted from Mandelbrot et al.

Similarly, the 2017 KDIGO “Guidelines for the Evaluation and Care of Living Donors” recommend the decision regarding donor candidacy be individualized for those with BMI >30 kg/m2. In 2016, 66% of living kidney donors in the United States were classified as having obesity, up from 61.5% in 2001. A study involving 90,013 living kidney donors showed significant differences in the BMI of accepted donors across various centers. The median odds ratio for donor acceptance varied from 1.10 for donors with overweight to 1.93 for donors with class III obesity (>=40 kg/m2). Moreover, at centers located in the ten states with the highest rates of general population obesity, the adjusted odds of being classified as a donor with severe obesity were 185% higher than in states with the lowest obesity rates. While some single-center studies have reported exclusion rates due to obesity ranging from 1.8% to 25%, it is still challenging to fully understand the extent of this issue, as individuals with obesity may be more likely to be excluded prior to undergoing a formal evaluation.

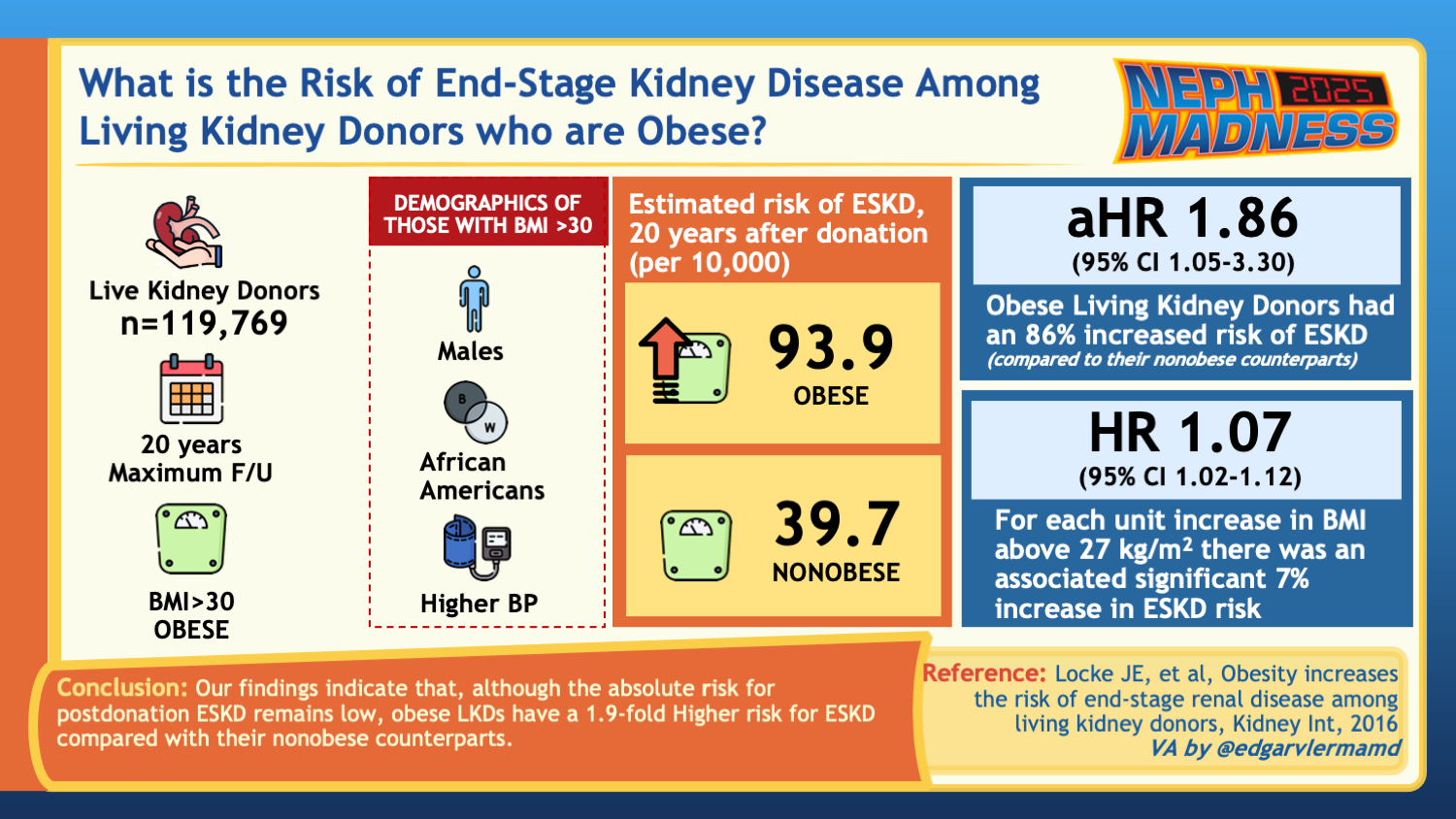

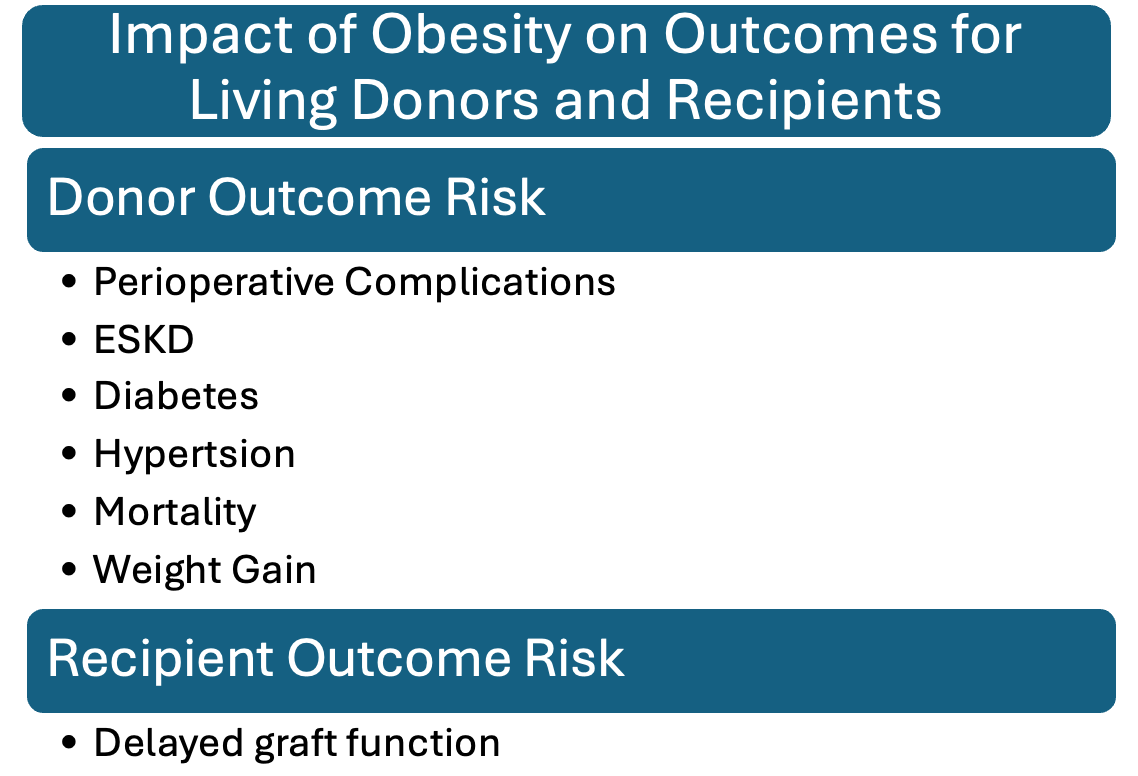

Although the literature is limited, obesity in the otherwise healthy living kidney donor portends some risks, highlighting the importance of risk mitigation. Obesity increases perioperative complications, though these have been reduced with newer surgical techniques. Donors with obesity are more likely to develop diabetes and hypertension, both of which are of earlier onset. Similarly, a study compared 1,558 adult living kidney donors with obesity to 3,783 adults with obesity; at a median follow-up of 3.6 years, the living kidney donors who gained more than 5% had an increased incidence of hypertension compared to similar nondonors. A national study of 119,769 living kidney donors at 20 years post-donation found a cumulative incidence of mortality of 304.3/10,000 for donors with obesity compared to 208.9/10,000 among the donors without obesity, with an increased risk detectable at 5 years post-donation. Some studies have investigated kidney outcomes with mixed results. Creatinine and GFR changes in the postoperative setting were similar amongst donors with and without obesity based on a single-center retrospective analysis. Another study found no statistically increased risk for end stage kidney disease (ESKD) development at 20 to 30 years post-donation among donors with obesity compared to donors without obesity, but the eGFR was reduced to 62 compared to 67 (p=0.05). On the other hand, a study with 119,769 donors in the United States demonstrated a 1.9 times increased risk for kidney failure in donors with obesity (p=0.04) and a 7% increased risk for kidney failure for every 1 unit increase in BMI above 27kg/m2 at the time of donation. Even those who were within the overweight category had an increased risk. Post-donation proteinuria is also increased in obese donors. Some studies have shown an increased risk of delayed graft function in recipients of kidney transplants from donors with obesity. The figure below summarizes these reported outcomes.

Data on long-term outcomes for living kidney donors with obesity are crucial for better understanding the associated risks for these patients.

To reduce these risks, there are several different weight loss options to consider for potential donors. Dietary, exercise, and behavioral modifications are recommended in conjunction with the consideration of pharmacological agents, metabolic surgery, and culinary medicine. An independent, comprehensive approach facilitated by a specialized weight loss clinic would be optimal.

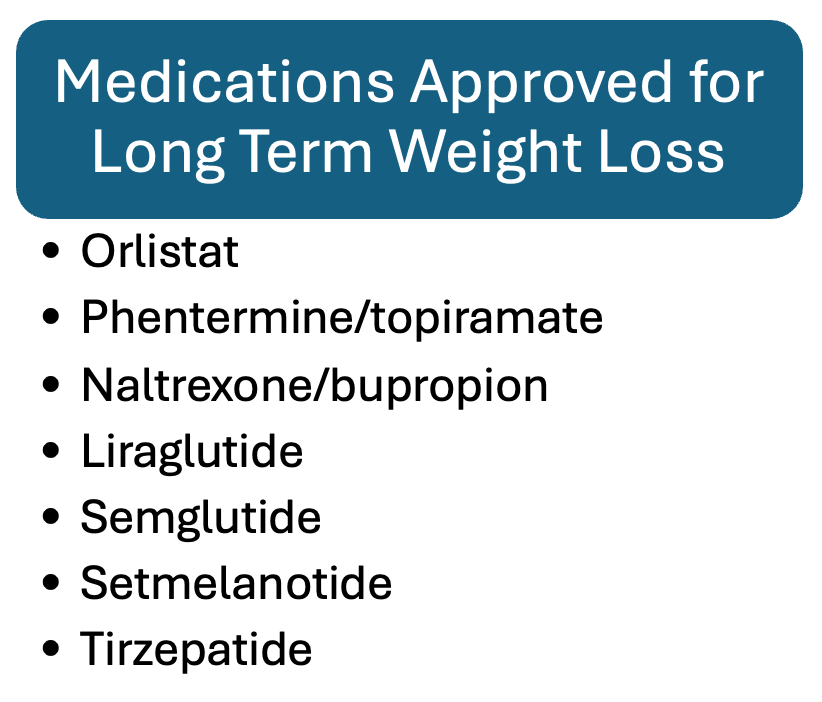

Numerous medications are available that can be individualized for the donors. Some potential options with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved weight loss medications are listed below.

Adapted from National Institute of Health data.

Additionally, metformin and SGLT2i have also been used off-label for weight loss. This integrated approach would aid in increasing qualified donors while optimizing their health and safety for donation with a particular emphasis on sustainability.

However, several challenges remain in both pre- and post-donation settings. For example, a retrospective observational study found that only 13% of patients with obesity were able to meet the transplant donor BMI threshold of 35 kg/m2 while following a monitored diet program and making lifestyle modifications. Even among donors who successfully lose weight, maintaining these behavioral and dietary changes, and possibly using pharmacological interventions, after donation can be difficult for various reasons.

There is some disagreement regarding the funding source for obesity-related interventions, which may be more accessible to donors during the limited pre-donation period. Given that obesity management is lifelong, donors will need to have access to lifelong medical care. Furthermore, it is important to consider the side effect profiles of pharmacological therapies and whether the desired effects are sustainable. For instance, in a non-transplant population, a placebo-controlled trial included patients with obesity or a BMI >27 kg/m2 and an obesity-related comorbidity other than type II diabetes who were randomized to receive 68 weeks of semaglutide with lifestyle interventions or placebo with lifestyle interventions. The patients in the semaglutide arm regained 67% of their weight lost within the next year and their blood pressure increased back to baseline. Likewise, there is a significant concern about rebound weight gain after donation. A single-center study reported that 73% (403 out of 539) of donors had gained weight 15 years after donation. Among those who were obese and lost weight to donate, 12 out of 14 participants regained a considerable amount of weight post-donation. Another study indicated that post-donation weight gain was most pronounced in those who had lost weight before donation.

Further research is essential to ascertain the specific amount of weight loss and the duration of maintenance required to mitigate the risk of adverse health outcomes to levels comparable to those of similar nondonors and lower-weight donors.

Ensuring the protection and optimization of donor care is of utmost importance. This approach should include the implementation of sustainable lifestyle modifications and, when necessary, therapies that promote health both prior to and following the donation process.

In this episode of The Nephron Segment, hosts and long-time NephMadness masterminds Samira Farouk and Matt Sparks are joined by transplant nephrologist Swee Levea & transplant surgeon Babak Orandi:

Episode 16: NephMadness & Obesity & Kidney Transplantation

Team 2: Obesity in Kidney Transplant Recipients

Copyright: franz12 / Shutterstock

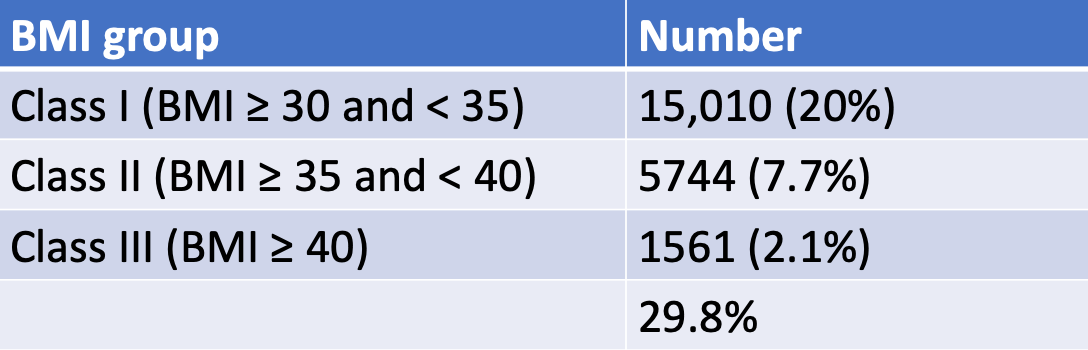

It has been well described that obesity is common at the time of kidney transplant, with up to 30% of patients receiving a kidney transplant having obesity. Importantly, about 2% have been described as class III obesity with a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2.

Adapted from Cannon et al.

Obesity has important implications in regard to post-kidney transplant outcomes. Patients with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 were twice as likely to develop complications with wound healing than their counterparts without obesity.

Additionally, obesity plays a significant role in metabolic syndromes and is a major risk factor for CVD, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus. CVD remains a leading cause of mortality in kidney transplant recipients, and obesity is an independent predictor for CVD post-transplantation.

Obesity also contributes to the development of PTDM. Increased adiposity can lead to mild inflammation and dyslipidemia, leading to impaired glucose metabolism and insulin resistance. In addition, immunosuppressant medications such as glucocorticoids can cause hyperglycemia and induce pancreatic beta cell apoptosis. Calcineurin inhibitors have direct toxic effects on pancreatic beta cells. PTDM is diagnosed at least 6 weeks after kidney transplantation when any of the following criteria are met: a fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, symptoms of diabetes such as polyuria, polydipsia, or unexplained weight loss, and a random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL, or a glycated hemoglobin (HgA1c) ≥ 6.5% three months post-transplant. Although the evidence is varied, there is some suggestion that PTDM may be linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in transplant patients.

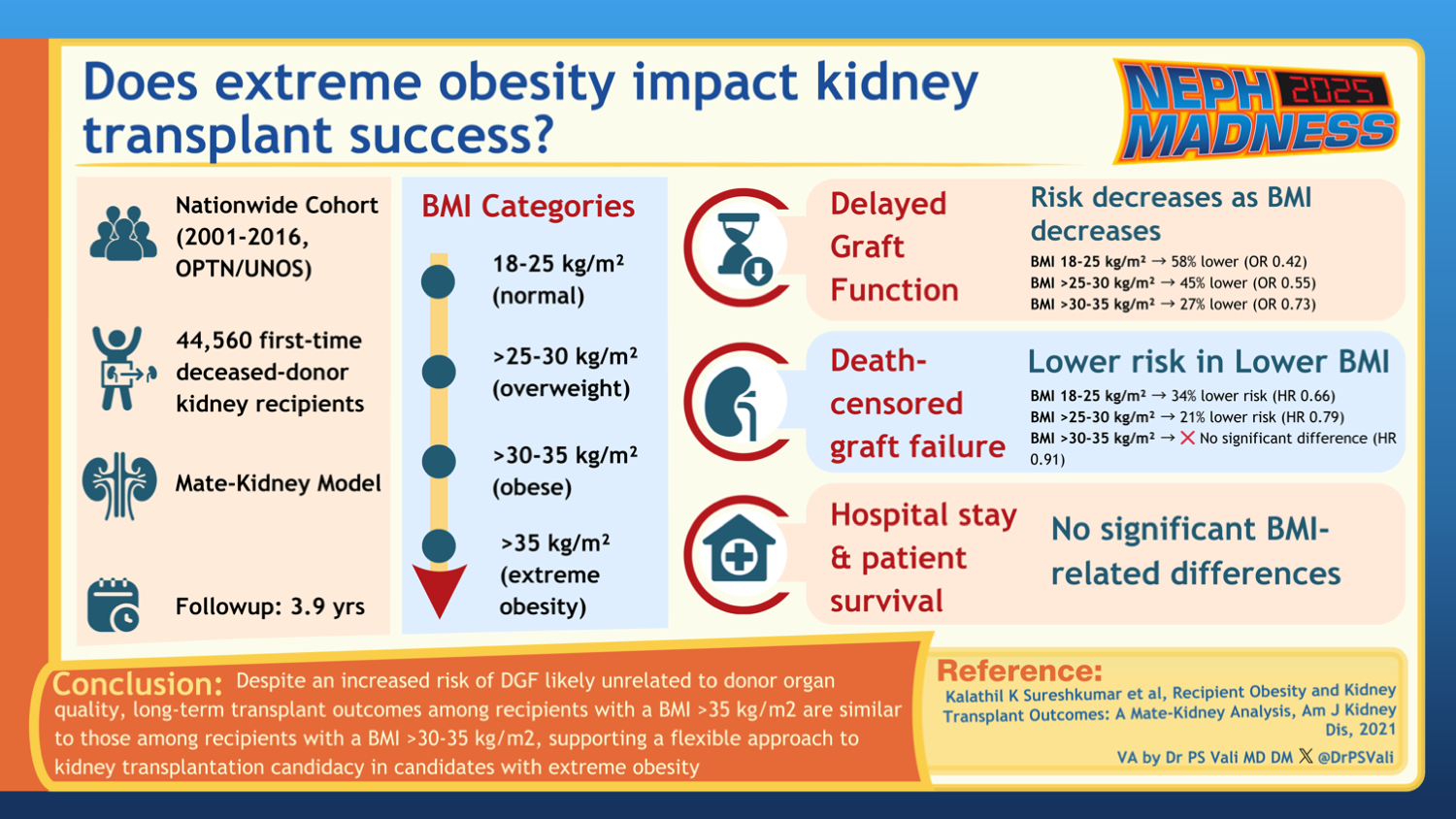

Several studies have demonstrated an increased incidence of delayed graft function (DGF) and increased graft loss over 7 years in patients with obesity. A recent retrospective analysis showed that graft outcomes were better for those with a BMI ≤ 30 kg/m2 than those with a BMI > 35 kg/m2. DGF was less common in patients with a BMI between 30-35 kg/m2 than in recipients with BMI > 35 kg/m2.

Weight gain after kidney transplantation is common. A retrospective study in Brazil showed that upwards of 30% of kidney transplant recipients gained at least 10% of their baseline weight within the first year of transplant. Therefore, it is crucial to identify and address obesity following kidney transplantation.

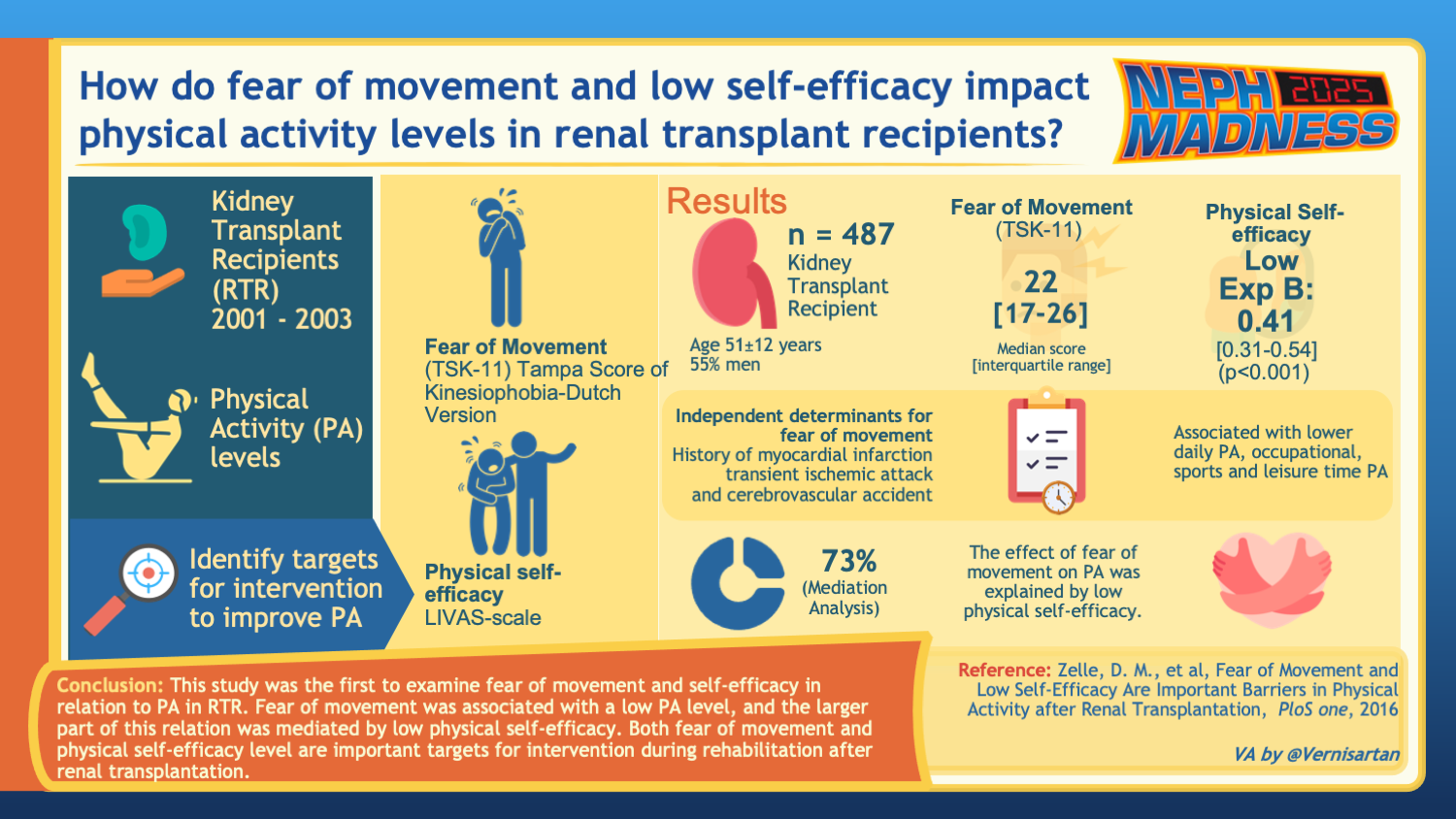

Notably, data from an Italian National Transplant Center showed that kidney transplant patients with obesity were less likely to engage in physical activity of > 150 min/week and spent more time seated. Further, there can be transplant-specific factors that can be barriers to exercise. Interestingly, one study found that kidney transplant recipients fear movement due to concerns about hurting the allograft kidney. These patients also had low self-efficacy or low belief in their capability to perform exercise, which worsened their fear of movement. It is essential for healthcare providers to offer reassurance that exercise can be safely undertaken without compromising the health of the transplanted kidney and to cultivate a stronger belief in the patients’ capacity to engage in physical activity.

The late great UCLA basketball coach John Wooden once said, “We can have no progress without change.” Therefore, it is not surprising that most guidelines recommend lifestyle interventions for primarily sedentary individuals. Although the overall data on physical activity in KTRs is limited, it is still recommended that patients should engage in regular aerobic exercise for at least 30 minutes, 5 times per week, along with strength training at least 2 times per week. Notably, Medicare will cover weight-loss counseling, and some Medicare Advantage plans may include coverage for gym memberships and food delivery programs.

Diet after kidney allograft transplantation is also of utmost importance. Patients with end-stage kidney disease are often at high risk for malnutrition. While kidney transplants usually improve nutritional status, KTRs have their own nutritional risks, including weight gain, PTDM, and hyperlipidemia. The National Kidney Foundation recommends a well-balanced diet with controlled portion sizes after kidney transplantation. Often, KTRs are in the habit of avoiding healthy foods such as fruits due to their potassium content. It is important to remind our patients that fruits and vegetables are okay to consume. Energy needs can be calculated to help meet a healthy weight goal, with intake being around 25 kcal/kg/day. Six weeks after transplantation, carbohydrates are typically recommended to be less than 50% of total calories.

If intensive lifestyle interventions are unable to achieve and maintain sufficient weight loss, then some patients may benefit from medications. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agents seem to be the rising star when it comes to weight loss, and Gila Monster was the winning team of NephMadness 2024. GLP-1s are gut-derived hormones that increase insulin secretion from the pancreas and inhibit glucagon secretion. They also reduce gastric emptying. There has only been one retrospective study assessing GLP-1 effectiveness in KTRs. It was shown that dulaglutide up to 1.5mg weekly helped reduce the BMI by up to 2 kg/m2 without changes in tacrolimus levels. Metformin is a well-known drug that inhibits liver mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase and helps improve insulin sensitivity. However, its use post-kidney transplant is uncommon due to clinicians’ fear of lactic acidosis in kidney impairment. In fact, a retrospective evaluation of U.S. transplant registry data between 2008-2015 showed only 4.7% of patients with pre-transplant diabetes filled metformin within one year of transplant. There was no evidence of adverse graft or patient outcomes with metformin. Instead, metformin may be associated with lower all-cause mortality. Another study found that patients on the combination of metformin and the dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor had better weight loss than patients on insulin and may be a viable option for patients with stable kidney function.

If intensive lifestyle interventions and pharmacotherapies are insufficient for weight loss, it is recommended that patients be evaluated for bariatric surgery. Overall, the data investigating the role of bariatric surgery after kidney transplantation is scarce. Bariatric surgery has been shown to reduce BMI compared to lifestyle management alone in KTRs. Kidney transplant recipients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) procedures may have a slight increase in mortality in comparison to the general population; however, these patients still tend to lose anywhere from 30-60% of excess body weight. Both laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and RYGB have similar postoperative outcomes with weight loss and improvement in comorbidities. Interestingly, both seem to be associated with a reduction in urinary protein excretion in KTRs, presumably due to an improvement in obesity hyperfiltration. Importantly, tacrolimus dose was higher in the bariatric groups, likely due to decreased absorption of medications. Thus, the optimal timing of bariatric surgery may be 6-12 months after kidney transplantation when immunosuppression trough levels are more stable, and small variations in immunosuppression trough levels would have a limited impact on the allograft.

Overall, achieving and subsequently maintaining weight loss is important in patients with kidney transplants, and nephrologists will likely play a critical role in supporting patients through this process. Despite the negative impact of obesity, it is important to remember that kidney transplant recipients who are overweight still perform better than patients with obesity and end-stage kidney disease who are wait-listed for transplant.

Adapted from Glanton et al.

As a result, it is imperative that we find ways to transplant these patients safely. Once these patients undergo kidney transplantation, we must continue to work as part of a multidisciplinary team to address and manage obesity effectively. Each treatment approach must be individualized to meet the patient’s specific needs. Fortunately, a comprehensive array of strategies exists to facilitate weight loss, including lifestyle interventions, weight loss medications, and bariatric surgery.

– Executive Team Members for this region: Anna Burgner @anna_burgner – @annaburgner.bsky.social and Jeffrey Kott @jrkott27 – @jrkott27.bsky.social | Meet the Gamemakers

How to Claim CME and MOC

US-based physicians can earn 1.0 CME credit and 1.0 MOC per region through NKF PERC (detailed instructions here). The CME and MOC activity will expire on June 1, 2025.

Leave a Reply