#NephMadness 2024: Hyponatremia Correction Region

Submit your picks! | NephMadness 2024 | #NephMadness

Selection Committee Member: Mirjam Christ-Crain @ChristCrain

Mirjam Christ-Crain is Full Professor and Deputy Chief of Endocrinology at the University Hospital of Basel, Switzerland. Her main research interest is on vasopressin-dependent disorders of fluid homeostasis, i.e. vasopressin deficiency and hyponatremia. She authored and co-authored more than 300 publications and received several honors and awards for her research.

Naman Gupta is a first-year Nephrology fellow at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA. He completed his residency in Internal Medicine at Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh, PA. His clinical and research interests include chronic kidney disease, cardio-renal syndrome and urine microscopy.

Writer: Alisha Sharma @AlishaSharmaMD

Alisha Sharma is a first year Pulmonary & Critical Care fellow at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA. She completed her residency at Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh, PA. Her areas of interest include critical care medicine, pulmonary hypertension and interventional pulmonology.

Writer: Graham Gipson @grahamgipsonmd

Graham Gipson is an academic nephrologist at VCU Health / VCU SOM in Richmond, VA. His major area of interest is propagation of the “Dark Arts of Nephrology” through education, with a special emphasis on quantitative clinical physiology, clinical chemistry, and the history of nephrology through the ages.

Competitors for the Hyponatremia Correction Region

Team 1: Rapid Correction

versus

Team 2: Slow Correction

Image generated by Evan Zeitler using Image Creator from Microsoft Designer, accessed via https://www.bing.com/images/create, January, 2024. After using the tool to generate the image, Zeitler and the NephMadness Executive Team reviewed and take full responsibility for the final graphic image.

Many times in life, those who do the most correcting, need the most correcting.

– Orrin Woodward

Introduction

Hard to believe it’s been 6 years since players from this dream team competed in NephMadness! Hyponatremia awes generations of fans but rarely rewards loyalty with easy victory. We the nephrologists, the keepers of this chemical deity, have constructed an obstacle course around it. As we invite our trainees onto the track, nothing about hyponatremia is what it seems. Consider the word itself: hyponatremia—low (hypo) sodium (natr[ium]) in blood ([a]emia). A Greco-Latin mash-up brimming with misdirection. All nephrologists know that hyponatremia is a disorder of water in relative excess of sodium and potassium. But as soon as we declare “Hyponatremia is a water, not a sodium problem”, a few of our followers hang back and start looking for an exit.

As we move on, we classify hyponatremia according to clinical volume status. Now, volume is another fraught term. To most, volume refers to the physical space occupied by a given fluid. But to a nephrologist, volume, with all its water, is nothing without the solute blend that endows its physicochemical properties, and chief among those solutes, sodium. We state, “Volume abnormalities are really sodium problems”, and more followers drop out.

What awaits those faithful followers who have arrived with us at the center of the hyponatremia mystery? The treatment of this water problem with…sodium! Whether it is severe symptomatic hyponatremia or moderate asymptomatic one – Doc Schmidt is right, salt is the medicine! As you share this with the stunned disciples, you may or may not have the heart to mention that our way out is a lot more convoluted than the way in. The rate of correction! The danger of overcorrection! The possible need to backtrack! Should we be surprised to find a rebellion on our hands? Some of the followers who had drifted off or had made it to the center, or even some of our own “initiated” nephrologists have now decided to blast their way out! Are they genius? Are they mad? Should we let them? NephMadness was meant for this debate!

Team 1: Rapid Correction

“I feel the need…the need for speed.” Top Gun, 1986

Copyright: fuyu liu/Shutterstock

Over the years, a solid consensus has formed among physicians, particularly nephrologists, on the management of severe hyponatremia. This consensus culminated in international guidelines emphasizing a meticulous approach to correction rates aimed to minimize iatrogenic neurologic complications. Let’s review what these guidelines state (also, don’t forget to watch replays of the memorable match of NephMadness 2018: Hyponatremia Region):

- The European Guidelines advise limiting the correction of hyponatremia by 10 mmol/L on the first day and 8 mmol/L on subsequent days.

- The American Guidelines recommend to correct chronic Na < 120 mmol/L by 10-12 mmol/L/24 h, 18 mmol/L/48 h, and no slower than 4-8 mmol/L/24 h. For high-risk patients (with alcohol use disorder, hypokalemia, malnutrition, or advanced liver disease), the panel suggests a maximum correction rate of 8 mmol/L/24 h and minimum 4-6 mmol/L/24 h.

- For severe symptoms guidelines advocate bolus infusions of hypertonic saline to raise serum sodium by 5 mmol/L (European) or by 4-6 mmol/L (US) within a few hours.

Envision the dynamic game of maintaining serum sodium balance as a fast-paced basketball match where the stakes are high. Hyponatremia akin to a formidable opponent poses risks such as increased intracranial pressure and impaired cerebral blood flow. Opting for a rapid correction of hyponatremia can be likened to executing quick and precise plays on the court. Before we debate on whether or not rapid correction should be the approach, let’s discuss its most feared consequence, Osmotic Demyelination Syndrome (ODS).

ODS was first reported in 1959. Its association with rapid correction of chronic hyponatremia was established in 1980s, via animal studies and concordant patient observations. Pathogenesis is postulated to be the result of osmotic injury and apoptosis of glial cells. ODS can be also observed in patients with alcohol use disorder, hypokalemia, severe liver disease, malnutrition, hyperemesis, hyperglycemia, hypophosphatemia, and central nervous system hypoxia, with or without hyponatremia. Why? These factors impair the ability of astrocytes to adapt to rising extracellular tonicity by taking in organic osmolytes. The triggering factor precedes symptoms and demyelination by 1 to 14 days. The initial signs can be altered consciousness, delirium or impairment of memory and concentration. The manifestation of quadriparesis and pseudobulbar palsy, culminating in the infamous “locked-in syndrome” signifies the involvement of cortico-spinal tracts in the pons or midbrain, categorically termed as Central Pontine Myelinolysis (CPM). Cranial nerve complications or ataxia indicate extension to Extrapontine Myelinolysis (EPM).

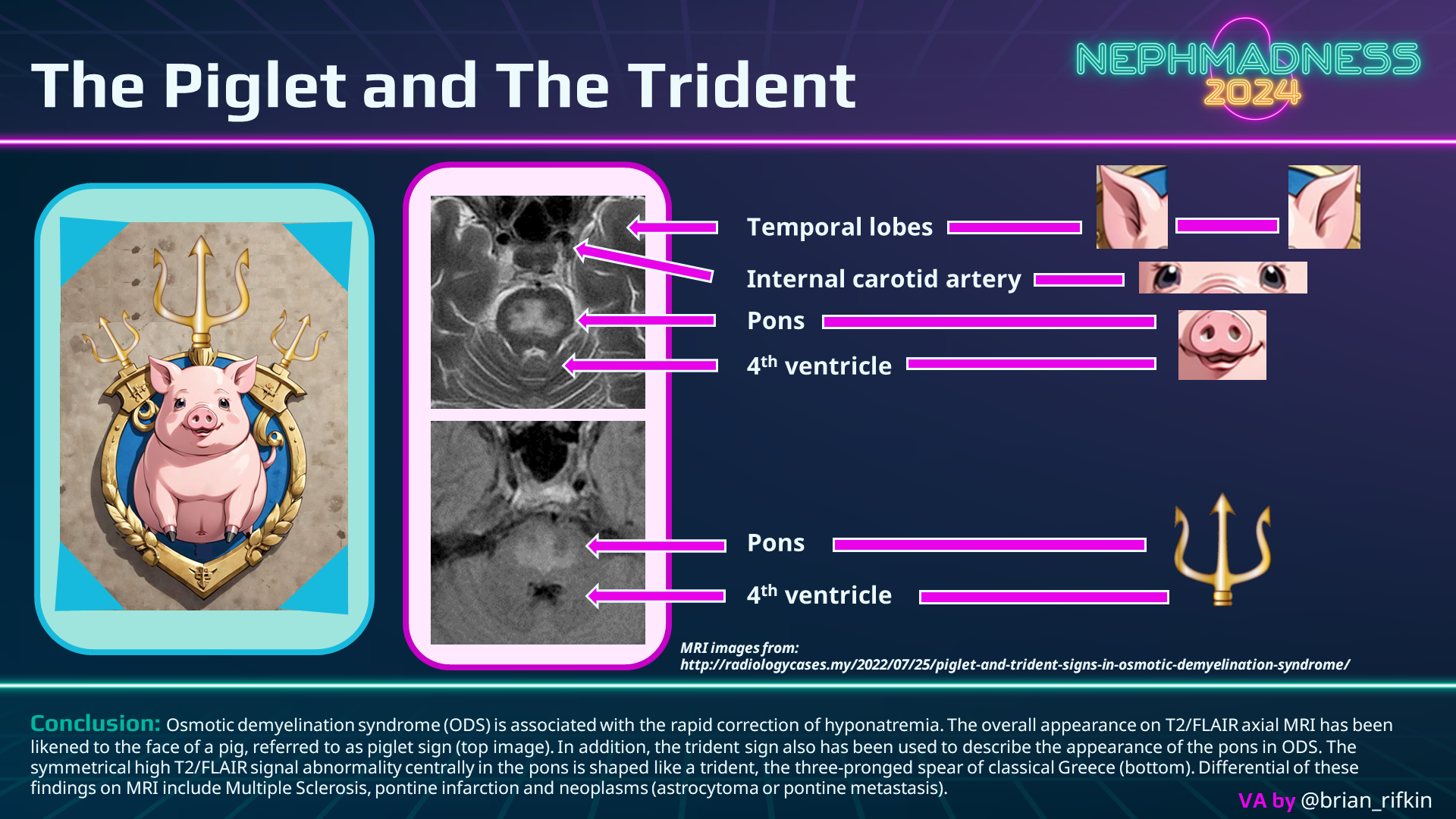

Clinical diagnosis relies on recognizing the characteristic presentation within the relevant context. While neuroimaging is used to confirm the diagnosis, it’s noteworthy that imaging findings may be delayed up to 3 weeks post the onset of the disease. In CPM, MRI reveals a “piglet” or “trident”-shaped lesion at the base of the pons (see graphic below), diffusion-weighted imaging may accelerate the diagnosis.

Examining the game statistics (also known as ODS cases) in the most comprehensive 2014 meta-analysis, among the 541 patients with ODS, the most common predisposing factor was hyponatremia (78%) and presentation – encephalopathy (39%). More than half of the ODS cases eventually had recovery (except for liver transplant recipients), and mortality even with severe neurological presentation has been decreasing with each passing decade. And to keep ODS at bay, meticulous hyponatremia correction has long been the rule of the court.

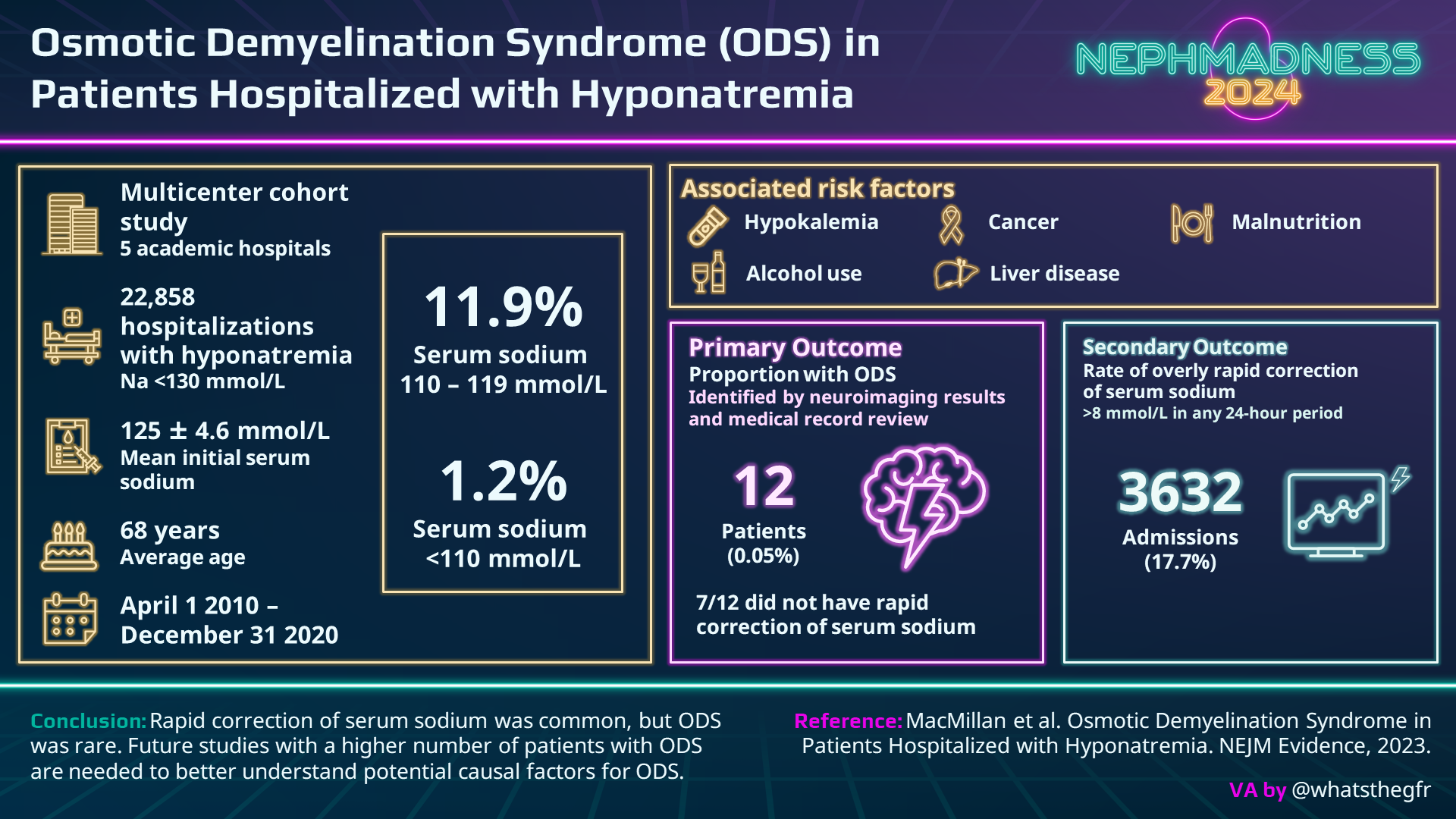

Enter the 2023 “disruptor paper” by MacMillan et al. This is an extremely large study of 22,858 admissions with hyponatremia, where 17.7% had a serum Na correction faster than 8 mmol/L in any 24-hour period, and the lowest Na group saw the highest risk of overcorrection. Patients with an initial serum Na <110 mmol/L underwent rapid correction 70% of the time compared with 46% of the Na 110-119 mmol/L group and 13% of the Na >120 mmol/L group. Nevertheless, even in the lowest Na group, ODS occurred in less than 1/1000. We must accept the potential for rapid correction in our patients despite best efforts. The possibility of ODS is certainly there BUT is it causal? In MacMillan et al.’s cohort, 7 out of 12 patients that developed ODS had hypokalemia, and a plurality had a positive alcohol level and a serum sodium <110 mol/L. The preponderance of high-risk patients in MacMillan’s ODS groups without clear relationship to the rate of correction should give us all a pause.

To add to the controversy, a retrospective study by Kinoshita et al. examined patients in ICU with a serum sodium concentration of < 120 meq/L. The slow correction group (< 8 meq/L/day, n = 573), when compared to the rapid correction group (> 8 meq/L/day, n = 451), had a significantly higher in-hospital mortality (13.4% vs 8.4%) and less hospital-free days (17.90 vs 18.88) without significant differences in neurological complications. Not a single ICD-9 code for ODS was found in this relatively small cohort.

A larger retrospective study by Seethapathy et al. found that limitation of severe hyponatremia correction rate was associated with higher mortality. The investigators compared slower corrected group (< 6 meq/L/hr) with standard (6-10) and faster corrected groups (>10). Odds ratio for in-hospital mortality in the slower group compared with standard was 1.7, and in the faster group – 0.6. Likewise, the odds ratio for 30-day mortality was 2.1 in the slower group and 0.69 in the faster group. Slow correction did not improve the rates of ODS, but the typical risk factors of hypokalemia, alcohol use, and malnutrition were present in those affected.

In a game where decreased length of stay and hospital-free days dominate the field, nephrologists tend to completely disregard these key metrics when it comes to hyponatremia. We seem to be enamored with “old-school” basketball where the mid-range jumpers reigned supreme. Our question to the reader is, what’s wrong with splash brother style basketball if it can also ultimately be the winning recipe to correct one’s sodium? Our expanding knowledge about hyponatremia and ODS tells us that fast correction is not the enemy it once was. We are as likely to stir trouble while driving snail-like on the highway as darting through a school zone at lightning speed.

The existing treatment guidelines, much like a conservative basketball playbook, might be overly restrictive and could be contributing to adverse outcomes. The studies by MacMillan, Seethapathy, and Kinoshita et al. spoke up for the silent majority by challenging the nephrology community to reappraise our strategy. Just like glial cells, we need to be more flexible. We need to tailor our treatment to the patient at hand, knowing that most will be at low risk for ODS and should fare better with a speedier correction. Does our patient have a history of alcohol use disorder? Are they malnourished and have hypokalemia? These are the patients we should be cautious with, but otherwise let’s abandon the traditional playbook for the fast-paced correction of today’s offense.

As eloquently stated in the NephJC summary: “We are left to wonder if our guidelines would have advocated so strongly for slower correction, had the large observational studies we have today come out before the much smaller cohorts on which they were drafted.” Let’s simplify the game plan, allowing for more proactive care. It’s time for a strategic rewrite of the playbook to ensure a winning season for patients facing severe hyponatremia!

COMMENTARY BY HARISH SEETHAPATHY:

Questioning the Status Quo

Check out this double podcast episode of The Intern At Work written by Caitlyn Vlasschaert and reviewed by Jeffrey Kott and Laiya Carayannopoulos:

228. It’s a Water Problem – An Approach to Hyponatremia

&

229. Ask a Fellow – Hyponatremia Rate of Correction

Team 2: Slow Correction

“We urgently need people to concentrate on the meaning of life rather than simply the speed…of it” – Joan Chittister

Copyright: DarSzach/Shutterstock

Hyponatremia is considered a problem of the modern age. The ability of physicians to intravenously intervene on a patient’s chemical anatomy gave rise to the notoriety of hyponatremia and its complications since the mid-1950s. But contemporary problems can often benefit from a history lesson. Antiquity, which saw neither hyponatremia nor basketball, can advise on both.

Festina lente was a Greek principle adopted by Roman emperors two millennia ago: proceed urgently but carefully. This concept is embedded in the titles of three superb papers:

- Therapy of hyponatremia: does haste make waste? (Narins, 1986);

- Treatment of symptomatic hyponatremia: neither haste nor waste (Arieff and Ayus, 1991); and

- Treating hyponatremia: why haste makes waste (Sterns, 1994).

This trio captures the contentiousness of the hyponatremia correction rate problem as it stood in the 1990s. In the wake of the “disruptor paper” from MacMillan et al. in 2023, Dr. Richard Sterns, an ardent proponent of slow correction, assembled an all-star defense to reinforce his fundamental message, festina lente.

The golden age of hyponatremia investigation, characterized by meticulous case reviews and multispecies animal models, established two irrefutable facts. First, overcorrection of hyponatremia can lead to osmotic demyelination. Second, the biological basis for adaptation to (and de-adaptation from) osmotic stress has a definite temporal structure and particular cellular physiology. In response to these facts and the accumulation of data on ODS, hyponatremia correction rates have slowed down over years, culminating in the DDAVP clamp as standard of care. To be fair to our opponent team, over 50% of ODS lesions can exhibit regression over time and may not necessitate specific therapeutic interventions, but these events are still not to be discounted. See this award-winning 6-min animated short with a fascinating testament from a patient.

The “disruptor” paper from MacMillan et al. whence this region sprung, challenges the tradition and status quo on the most common and complex disorder of human biochemical pathology. Accordingly, a stir-up of strong opinions has ensued. (The fans can review the visual abstract of the MacMillan paper in the previous scouting report.) Why hasten to throw away the age-old consensus on the rate of correction of hyponatremia? Are we that disturbed by the increased length of stay and practical aspects of frequent lab checks, or is there something else that unsettles us? Is it because rapid correction offers a swift, simple alternative to the tedium of slow correction and its multiphase details? Most cases of hyponatremia are, at their cores, cases of some other primary disease process; hyponatremia is their biochemical collateral damage. We argue that hyponatremia fallout—increased morbidity and mortality, increased hospital length of stay, increased resource utilization—is as much a function of the primary disease as it is of hyponatremia itself or its correction rate. This argument does not discount hyponatremic encephalopathy (from under-correction) or ODS (from over-correction) as paramount for patient outcomes. A large study is ongoing comparing strict versus “standard” (less strict) correction in terms of morbidity and mortality. Until then, we do not know whether poor outcomes are due to hyponatremia, its treatment or the underlying disease. Applying “one size fits all” therapeutic rules and rushing about wantonly enforcing normonatremia may create more problems than those we mean to avoid.

A more recent emperor and movie protagonist, Napoleon Bonaparte, may or may not have pronounced another maxim, “Quantity has a quality all its own”. Our “disruptor paper” by MacMillan et al. delivers on quantity which does not necessarily beget quality. Perhaps the most valuable facet of this study is its confirmation of what we’ve known for decades about hyponatremia and its correction, just on a vastly larger scale. Our slow-growing snowball of hyponatremic ODS cases—with the original case series tucked snuggly at its core—is dwarfed by the size of MacMillan’s cohort. The major value of the MacMillan et al. stems from the investigators’ leverage of big data to confirm what we’ve known all along: ODS is a rare complication of hyponatremia correction. What the “disruptor paper” does NOT provide is an evidentiary stronghold from which to wage war on careful correction of hyponatremia in patients at greatest risk of ODS. Rare should not translate into reckless. Even though the disruptor reaffirms previous conclusions about ODS incidence, the present work suffers from significant limitations. All limitations fall under the conceptual umbrella of under-sampling:

- First, ODS was adjudicated using neuroradiologic data. Historically, ODS (then bearing the narrower label CPM) was diagnosed at post-mortem neuropathological examination. This point is more a matter of construct validity but is important enough to merit mention. Even if neuroradiology provided perfect diagnostic information, the timing of neuroimaging is the next hurdle to overcome. Specifically, neuroimaging done too early may miss nascent ODS.

- Second, 64% of all hyponatremia cases (14,658 of 22,858) were never imaged at all. When exploring the intersection of ODS and rapid correction, the percentage of non-imaged cases is even larger at 71% (14,658 of 20,572). Thus, the “disruptor” paper suffers from denominator inflation. After discarding non-imaged cases, the new ODS incidence overall is 0.15% (12 ODS events out of 8,200 imaged cases), and the new ODS incidence associated with rapid correction is 0.06% (5 ODS events associated with rapid correction out of 8,200 imaged cases). So is ODS still rare? Yes, but with a more conservative denominator, the incidence is 3-fold that reported in the paper (0.15% instead of 0.05%).

- Third, the “disruptor” report by MacMillan et al. gives the impression that assessment of rapid correction was done over only two intervals, 0–24 h and 24–48 h; ignoring other possible intervals. The investigators donned “kinetics blinders” and consequently may have missed many rapid corrections.

- Fourth, the study’s time-point benchmarks of interest are 24 h and 48 h, but they are bloated with 6-h margins on either side. The lower margin (18–24 h) increases the risk of missing rapid correction, whereas the upper margin (24–30 h) increases the risk of over-diagnosing rapid correction. This as well as the previous limitation could have been avoided with linear interpolation.

In summary, undermined by numerically bountiful but relatively content-anemic data, the “disruptor” paper offers up a modest-resolution inquiry into the incidence of ODS. ODS is a little like Schrödinger’s cat: the brain cells could be alive or dead; to know which, one must look inside the (brain) box. For now, we should recognize ODS for the danger it is, appreciate its rarity while remembering its favored prey, and when compelled to act, heed the ancient wisdom of festina lente.

Let’s now turn our attention to the other papers in favor of rapid correction. Kinoshita and colleagues dazzle us with statistical glam but their conclusions fall short on novelty. Their core message is not that different from saying, “Risk of car accident is directly proportional to my time on the road, therefore I must drive as fast as possible”. Well… Slow correction entails more time. Their conclusion about lower in-hospital mortality for rapid correctors rings hollow. What about all those confounders along the way from hyponatremia to mortality? Until we prove a direct causal link between rapid correction and lower mortality, let’s hang our basketball hats elsewhere before cranking the throttle on correction.

Seethapathy et al. arrive at the same conclusion: achieving a goal takes longer if you move slower. Their work represents a blend of Kinoshita and MacMillan in that they explore mortality and ODS incidence. Their adjudication of ODS was, sadly, even narrower than MacMillan’s, limited to MR neuroimaging, altogether missing asymptomatic and oligo-symptomatic cases which may not trigger an MRI order.

All three of the abovementioned “disruptor papers” would do well to beef up the rigor of their kinetics analysis. On the whole, they form a nice springboard for further investigations, but offer only flimsy justification for abandonment of slow correction.

Conclusion

To a busy clinician it may be attractive to treat hyponatremia as a one-size-fits-all affair, but this would be unwise. This year’s hyponatremia region may similarly appear to pit slow correctors against fast correctors, but this too is not quite the case. Three recent publications have stirred the controversy pot for an issue that’s simmered for almost 30 years. Each paper demonstrates how challenging it is to analyze hyponatremia treatment and its complications. We remain wedged between the peril of under- and over-treatment. An oft-overlooked tenet of medicine is that all treatment should be individualized for any one patient rather than rubber-stamped en masse. Slow correction of hyponatremia is best for high-risk patients, but is indefensible as the strategy for all-comers (both medically and resource-wise). Similarly, rapid correction is too aggressive for “metabolically frail” patients, but is reasonable and lifesaving for many other patients. Going forward, our focus should fall on picking the right speed for the right case!

COMMENTARY BY MIRJAM CHRIST-CRAIN:

Primum Non Nocere!

COMMENTARY BY RICHARD STERNS:

Grilling New Data on ODS: Rare or Just Not Well Done?

– Executive Team Members for this region: Anna Vinnikova @KidneyWars and Timothy Yau @Maximal_Change | Meet the Gamemakers

How to Claim CME and MOC

US-based physicians can earn 1.0 CME credit and 1.0 MOC per region through NKF PERC (detailed instructions here). The CME and MOC activity will expire on May 31, 2024.

Submit your picks! | #NephMadness | @NephMadness

Thanks for the insightful & engaging commentary on this important issue.

However, there are inaccuracies in the blog post, especially regarding the purported limitations of the MacMillan et al. NEJM Evidence paper.

Regarding the THIRD purported limitation, the blog authors suggest that “assessment of rapid correction was done over only two intervals, 0-24h and 24-48h.”

In fact, we assessed for rapid correction during the entire interval from time of initial sodium measurement until either the sodium reached 130 mmol/L, the patient died, or the patient was discharged from hospital.

Regarding the FOURTH purported limitation, the blog authors suggest that the study’s “time-point benchmarks of interest are 24h and 48h, but they are bloated with 6-h margins on each side).”

In fact, we did not use the 24h and 48h sodium values at all when evaluating for rapid correction. We reported these values in our Table 2 to allow for easy comparison between the ODS and non-ODS groups. However, we defined rapid correction as: the occurrence of a change in sodium of >8 mmol/L in any 24 hour period. For each subject, every sodium value was iteratively compared against every other sodium value during the analysis period to determine the outcome.

Our review of the kinetics overlooked the method for overcorrection surveillance from admission until one of the endpoints cited. The disclosure of the methods and of the study dataset in the paper was very succinct. Tables and figures, the fodder of busy clinicians, emphasize 0, 24 and 48 hours, potentially reinforcing a misperception that only the first 48 hours of hyponatremia treatment are relevant. We are grateful to Dr. MacMillan for taking time to engage with us on this important topic.