Death by Suicide Among People with Kidney Failure on Dialysis

Dr. L. Parker Gregg is an Assistant Professor at Baylor College of Medicine, the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, and the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety in Houston, TX. Her primary interests are in fatigue, depression, and cardiovascular diseases in people with CKD.

Helena Zhang, MD, completed her internal medicine training at Baylor College of Medicine and is currently a first-year nephrology fellow at Stanford University.

Dialysis is a life-sustaining intervention for people with kidney failure. In the context of the physical, physiological, financial, and lifestyle burdens of dialysis, people with kidney failure experience a disproportionately high incidence of depression, which affects approximately 23% of patients. Psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety are independently associated with increased risk for hospitalization and mortality, poor adherence to dialysis schedules and dietary restrictions, and poorer quality of life. Mental health disorders are also a risk factor for death by suicide. A prior study found that the rate of death by suicide from 1995 to 2001 among individuals with kidney failure was 24.2 per 100,000 patient-years, a rate 84% higher than the general population.

To better understand the risk of death by suicide among people with kidney failure on dialysis, Giang et al. conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) to examine trends over time and factors associated with death by suicide among adolescents and adults who initiated hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2020. Death by suicide was identified by the date and primary cause of death listed in the USRDS Patients and Death files. They expressed rates of death by suicide as 3-year moving averages. Multivariable models assessed the associations of patient characteristics including age, sex, race/ethnicity, dialysis modality, employment status, and income with the hazard of cause-specific death by suicide, treating death from other causes and receipt of a kidney transplant as censoring variables. Separate models assessed factors associated with death by suicide that occurred <4 years and ≥4 years after dialysis initiation.

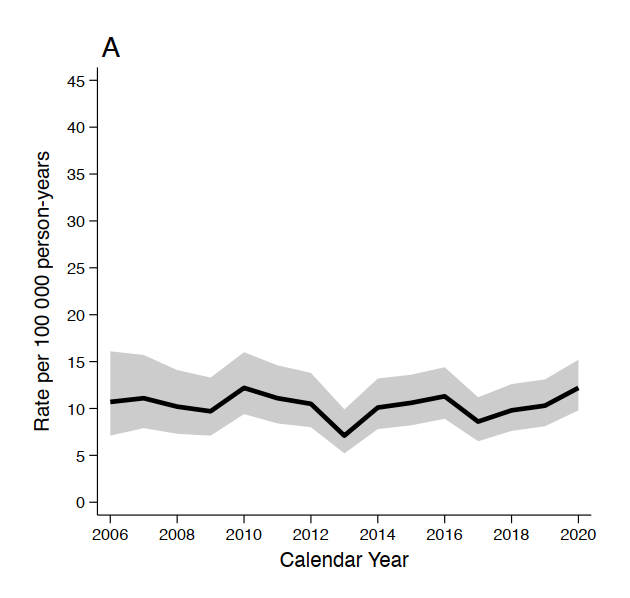

Out of 1,721,337 people in the cohort, 729 (0.04%) died by suicide, at an incidence rate of 10.3 (95% CI 9.4, 11.2) events per 100,000 person-years. The incidence rate was generally stable over time in the entire cohort and among subgroups. Deaths by suicide occurred a median (IQR) of 17 (5, 38) months after dialysis initiation. People who died by suicide were more likely to be men and of White race, but the distribution of age groups, cause of kidney failure, comorbidities, income, and dialysis modality were similar between those who died by suicide and the entire cohort. In multivariable models, male sex and White race were independently associated with higher hazards of death by suicide at both <4 years and ≥4 years (P<0.0001 for each). Higher risk for death by suicide ≥4 years after dialysis initiation was observed among individuals aged 12-29 years compared to those aged 75 years or older (aHR 3.77 [95% CI 1.56, 9.10], P=0.004). There was a significant sex by age interaction within 4 years after dialysis initiation, such that men aged 12-29 and 30-49 had lower odds of death by suicide compared to men aged ≥75 years, while no relationship between age and death by suicide was observed among women. They also found that lower income was associated with death by suicide within 4 years after dialysis initiation, and being retired (compared to being employed) was associated with a higher risk for death by suicide ≥4 years after dialysis initiation. Dialysis modality (peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis), comorbidities, etiology of kidney disease, and waitlist status for kidney transplantation were not associated with death by suicide.

Suicide rates from 2006-2020. The shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals. Crude incidence of suicide for the overall cohort. Figure 1 from Giang et al, © National Kidney Foundation.

This study offers valuable insight into the temporal patterns and demographic and clinical factors associated with the risk of death by suicide among individuals initiated on dialysis. It also indicates a need for further examination of the nuanced reality that encompasses the emotional and existential weight carried by those living with kidney failure across different demographic groups. For example, adolescents and young adults may experience disruptions in identity development, relationship building, employment, and life plans. Meanwhile, older adults may be more likely to struggle with progressive functional and cognitive decline, loss of independence, or fears of becoming a burden to others. These kinds of subjective experiences of kidney failure and their relationship to mental health crises may inform some of the differences seen between demographic groups.

Questions about quality of life, purpose, and the burdens of treatment become especially important in distinguishing death by suicide from end-of-life decision making that involves elective treatment withdrawal. Historically, dialysis withdrawal was viewed through the same lens as death by suicide, but clinical practice guidelines published in 2000 emphasized the central role of shared decision making in determining the appropriateness of continuing or discontinuing dialysis. Today, elective dialysis withdrawal is regarded as a reasonable treatment option for those with decision-making capacity. Appropriately, Giang et al. did not treat elective dialysis withdrawal as death by suicide in their study, although variability between individual clinicians in the selection of the primary cause of death on Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services forms may have misclassified some cases of elective dialysis withdrawal as death by suicide. This shift in perspective may account for some of the difference between this study’s results and the incidence rates of death by suicide reported from the 1990s, when death by suicide was also identified by USRDS records and considered separate from dialysis withdrawal, but more clinicians at the time may have documented dialysis withdrawal as death by suicide. This distinction highlights the importance of shared decision making and open communication to properly understand and honor a patient’s wishes as well as to identify people at risk for a preventable crisis.

Although not directly addressed by this study, these results also raise questions about possible relationships between death by suicide and serious mental illnesses among people with kidney diseases. According to one recent study, 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) diagnosis codes for serious mental illnesses, including major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, were prevalent in 7.4% of people with kidney failure, a 57% higher rate than the general population. Despite this, Giang et al. found that rates of death by suicide were similar to historical rates in the general population and lower than those previously reported among people with kidney failure. The authors optimistically suggest that this indicates progress in the recognition and management of factors predisposing to death by suicide among people with kidney diseases. Perhaps increased contact with the healthcare setting or increased awareness of depression and other mental illnesses in this population has facilitated chairside conversations with patients to ensure they receive treatment, but future studies would need to assess trends over time in mental health care utilization and antidepressant prescription as a proxy for this. There has also been an increased acknowledgement in recent years of the psychological stressors of kidney failure, indicating the need for a nuanced and individualized approach to psychosocial assessment and intervention that could include screening for and addressing mental illness, substance use, academic or work-related challenges, body image issues, social withdrawal, cognitive impairment, and loss of independence. Adequately treating related issues such as chronic pain may also help. In any case, it is encouraging that the rate of death by suicide is not increasing over time and is lower than what was reported in prior studies, despite the many challenges that people with kidney failure live with on a daily basis.

Figure 2. Available resources for people with kidney disease experiencing depression or suicidal thoughts. Resources are listed alphabetically within each section. This list may not be comprehensive, and additional resources may be available in your local area. © Gregg and Zhang.

If you, someone you know, or someone you take care of may have depression or be at risk for death by suicide, Figure 2 summarizes some of the available resources that may help, including both crisis resources and non-emergency resources such as support groups and peer mentor programs for people living with kidney disease. Those with active suicidal thoughts should be transported to the emergency department for immediate evaluation. Referrals to a mental health professional should be initiated for those experiencing persistent feelings of demoralization, difficulty coping, or significant impairments in daily functioning related to depression, anxiety, or other mental health concerns. Ongoing coordination between nephrology, dialysis unit staff, primary care, and mental health staff may strengthen continuity of care, recognition of people at risk for death by suicide, and timely access to resources for those in need.

-Post prepared by Helena Zhang and L. Parker Gregg

To view Giang et al (Free), please visit AJKD.org:

Title: Suicide in Patients Treated With Dialysis: Risk Factors and Trends in the United States

Authors: Sophia Giang, Feng Lin, Charles E McCulloch, Paul Brakeman, Thomas J Hoffmann, Elaine Ku

DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2024.12.013

Leave a Reply