#NephMadness 2025: Green House Region

Submit your picks! | @NephMadness | @nephmadness.bsky.social | NephMadness 2025

Selection Committee Member: Linda Awdishu @LAwdishu @lawdishu.bsky.social

Linda Awdishu is a Professor and Division Head of Clinical Pharmacy at University of California San Diego Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. Dr. Awdishu specializes in kidney disease and transplantation. She developed and practices in the Chronic Kidney Disease program at UCSD Health. Her research is focused on the pharmacokinetics of drugs in kidney disease and the pharmacogenomic predictors of drug induced kidney injury.

Writer: Rachel Khan @RFluriePharmD

Rachel Khan is an Associate Professor at Virginia Commonwealth University School of Pharmacy and pharmacist at VCU Health. She completed a Pharmacotherapy residency at the University of Maryland in 2014. She currently practices as clinical pharmacist in inpatient internal medicine and outpatient nephrology. Her interests include chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and electrolyte disorders.

Writer: Ethan Downes

Ethan Downes is currently completing his nephrology fellowship at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA before he goes on to complete a critical care medicine fellowship next year. His areas of interest include critical care nephrology, renal replacement therapy, and renal physiology.”

Competitors for the Green House Region

Team 1: Tubular Toxins

versus

Team 2: Oxalate Offenders

Image generated by Evan Zeitler using DALLE-E 3, accessed via ChatGPT at http://chat.openai.com, February 2025. After using the tool to generate the image, Zeitler and the NephMadness Executive Team reviewed and take full responsibility for the final graphic image.

“The beauty of plants is such that we often forget the dark side”

– Amy Stewart, Wicked Plants

Team 1: Tubular Toxins

Copyright: hwongcc/ Shutterstock

“Plant villains are just as riveting as their human counterparts.”

– Amy Stewart, Wicked Plants

You are preparing for clinic as a message appears in your inbox. The subject reads, “Can I take these??” A patient has sent you pictures of several packets with ingredients that are unfamiliar but you recognize they must be…herbal medicines! A moment of panic washes over you, “I didn’t learn about these in school; how am I supposed to answer?” Then you remind yourself that healthcare professionals are lifelong learners and the patient is trusting you to give them accurate information. Now what?

If this scenario feels personal, this is the region for you! Herbal medicines (HMs) are an essential part of healthcare in many countries and are common even in areas dominated by conventional medicine. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 80% of the world uses traditional medicines. In US adults, the use of nonvitamin, nonmineral dietary supplements (18%) was greater than any other complementary health approach. Most compounds in traditional Chinese, Indian, and African medicine come from globally used natural herbs. But do not assume that all naturally occurring HMs are safe! For instance, on the African continent, HMs have been implicated in 35% of acute kidney injury (AKI) cases. Moreover, patients at risk of AKI, i.e., those with known chronic kidney disease (CKD) or transplant, may also be consuming nephrotoxic HMs. Survey data from the United States revealed that 8% of patients with CKD are taking herbal supplements which the National Kidney Foundation specifically cautions to avoid. Consumption is surely higher in people with undiagnosed CKD. Studies from Switzerland, Turkey, and Germany confirm the widespread use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) in our patients.

CAMs, which include HMs, are not regulated or assessed for their safety and efficacy, nor are manufacturers required to report known or potential adverse reactions to the consumer. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US can legally act to remove supplements only when there is proof of harm, false statements, or deceptive labeling. Even then, continued consumption of these terrible tubular toxins can go on through illegal channels. Unfortunately, the precise poisonous substance and exact mechanism of nephrotoxicity can be unknown. The data that we do have on HM nephrotoxicity comes mainly from case reports which focus on acute injury rather than consequence of long-term use. In these reports, kidney biopsies are rarely done. The exact nephrotoxic culprit can be difficult to identify given that HMs are regularly mixed together and chemical analysis of the product may not occur. There are several possible ways HMs can hurt the kidneys. Besides direct toxicity from the plant itself, other mechanisms include contamination, adulteration, misidentification, and misuse. HMs may also have significant drug interactions with immunosuppressants leading to sub– or supra-therapeutic concentrations, with risk of acute rejection, AKI, or hyperkalemia.

The kidneys are a ‘terrific’ toxin target. As a major site of drug excretion and an organ that is processing a large volume of blood, their exposure to toxins is unrelenting. The renal tubular epithelium is especially vulnerable to injury due to such factors as broad surface area, high metabolic activity relative to oxygen supply, and its role in active drug uptake and urine concentration. The most common patterns of renal injury by HMs are acute tubular necrosis and proximal or distal tubulopathy. Reports of HMs causing tubular toxicity span the entire globe. Just like the 2024 Paris Olympic Games, these tubular toxins can really bring people together. Check out KDIGO’s world map of nephrotoxic HM for more information.

Several HMs are infamous for intrinsic tubular toxicity. A classic example is Aristolochia. It’s like the LeBron James of tubular toxins – the oldest player on the team yet still dominates! Aristolochic acid nephropathy is well described and actually used by researchers to mimic CKD in rodents! The earliest report of aristolochic acid nephropathy is from the 1960s, but it made headlines in the 1990s after a report of progressive kidney failure in nine women treated with a slimming regimen containing Chinese herbs in a clinic in Belgium. The compounded slimming medicine had a substitution of Aristolochia fangchi for Stephania tetrandra (both species are commonly referred to as fang ji). Hundreds of cases of aristolochic acid nephropathy have since been recognized, enveloping older terms of Balkan and Chinese Herb Nephropathies. The clinical presentation of aristolochic acid nephropathy is a rapid decline in glomerular filtration rate, evidence of proximal tubular dysfunction (glycosuria, metabolic acidosis, low-molecular weight proteinuria), and severe anemia. Albuminuria and edema are minimal or absent. Pathologic data reveal shrunken kidneys with extensive interstitial fibrosis and proximal tubular atrophy. Most patients progress to end stage kidney disease, and there’s a strong connection to urothelial cancer. Once aristolochic acid nephropathy was recognized, Aristolochia species were banned in many countries. Unfortunately, through contamination, adulteration, and lack of CAM regulation, this nephrotoxic compound continues to be relevant. Various species of Aristolochia are still grown in the Mediterranean, Africa, and Asia.

Glycyrrhiza, or licorice, is a “sweet root” as popular with nephrologists as Steph Curry with basketball fans. Who does not love to torment fellows with a discussion about how its metabolites, glycyrrhyzic and glycyrrhetic acids, skillfully produce hypertension and hypokalemia by blocking enzyme 11-ꞵ-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, thereby allowing cortisol to act freely on mineralocorticoid receptors! But this versatile sweet is also a tubular toxin capable of causing acute tubular necrosis (ATN) (in part via hypokalemic rhabdomyolysis) and proximal tubulopathy.

Senna species with their anthraquinone glycosides (sennosides) are valued for their stimulant laxative properties. Sennosides can be found in senna fruit, rhubarb, buckthorn, and aloe. A case report from Hong Kong described a patient presenting with dehydration and acute liver and kidney injury after consuming a proprietary oral slimming drug (sometimes referred to as detoxifying agent) which was purchased over-the-counter from a drugstore. Histological data displayed features of ATN and chemical analysis revealed Cassia obtusifolia as an ingredient in the slimming regimen consumed by the patient. Another case out of Belgium was a patient with acute liver and kidney failure from chronic ingestion of an herbal tea containing dry senna fruits (Cassia angustifolia). The mechanism of ATN is thought to involve direct accumulation of the anthraquinone glycosides in the kidney and indirect effects of hypokalemia and volume depletion.

Taxus celebica (common name is Chinese yew) is used in diabetes and other disorders. It contains a flavonoid that has been implicated in cases of acute kidney failure and hemolysis, found to be from ATN and other mechanisms.

Additional HMs from the African continent that have been histologically proven or highly suspected to cause ATN include the HMs Euphorbia paralias used as a diuretic, Cape aloes taken for constipation, and Callilepsis laureola taken for various conditions.

And if some of these HMs are unfamiliar to you, then you would surely recognize a tubular toxin by the name of colchium autumnale. While we are cautious in CKD with its derivative, prescription drug colchicine, poisonings with colchium autumunale mistaken for wild garlic have been reported in Croatia, Austria, and Slovenia, with a myriad of consequences including anuric ATN.

Tubular toxicity may also be indirectly related to HM through contamination with heavy metals during production, such as cadmium and cinnabar. These contaminants may transform a “nephro-neutral” HM into a bone fide tubular toxin. Clearly, tubular toxicity totally trumps any other mechanism of nephrotoxicity from HM.

Returning to our patient scenario, how to respond? While HMs may complement prescription medications, there are many barriers to appropriate evaluation of their use. Patients may be reluctant to admit use, perceiving that providers may have a negative or judging attitude and not understand their cultural practices. From the provider’s perspective, lack of teaching about CAM in formal medical education may make them feel unprepared to give recommendations and therefore avoid the subject altogether. In patients with CKD, KDIGO advises consultation with a pharmacist as part of a multidisciplinary team to optimize comprehensive medication management. KDIGO 2024 guidelines recommend routine inquiries about the use of HMs and to stop any unprescribed alternative remedy that may pose a threat of nephrotoxicity.

Patients can be referred to the National Kidney Foundation Herbal Supplements in Kidney Disease article. Accurate information about individual HMs is available for patients and health care professionals on NIH’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) website. NatMedPro is a comprehensive subscription database of natural medicines with summaries of their efficacy for different indications, adverse effects, drug interactions, and dosing.

Discussions about HMs should include a critical assessment of the efficacy and safety employing a patient-centered approach. In the US, if a patient is choosing a supplement with sufficient evidence for its use, advise them to choose a brand with the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) seal on the bottle. Manufacturers can voluntarily participate in USP’s Dietary Supplement Verification Program to help ensure the quality and safety of their products. USP conducts annual surveillance where products off store shelves are tested to ensure they continue to meet quality standards. The GMP (good manufacturing practices) seal verifies that the manufacturing process is approved by the FDA. Otherwise, studies have shown that there are large variations in the active ingredient content between brands and between batches. Please note that none of the process verification seals speak to the efficacy of the product!

1 https://www.nccih.nih.gov/, 2 https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/, 3 https://cam.cochrane.org/cochrane-reviews-related-complementary-medicine, 4 https://www.kidney.org/kidney-topics/herbal-supplements-and-kidney-disease

The WHO Traditional Medicine strategy 2014-2023 outlines objectives and actions to be taken to improve the safe and effective use of CAM, including the development of national policies, better regulation of products, practices, and practitioners, and promotion of universal health coverage including CAM. Calls to strengthen our knowledge and regulation of CAM and HM abound. Let’s do our part and talk with our patients!

COMMENTARY BY JOSH KING:

Let’s Not Avoid Nephrotoxins, Just for Today

Check out this podcast episode of The Poison Lab featuring Anna Vinnikova, Rachel Khan, Ethan Downes, and Josh King:

Episode 36 – Leafy Greens & Injured Beans: Natures Nephrotoxins

Team 2: Oxalate Offenders

Copyright: Utikhrt/ Shutterstock

“The line between friend and foe in the botanical world is often blurred.”

– Amy Stewart, Wicked Plants

It is time once again to make your picks and dive into the particulars on your way to filling out the bracket that will satisfy your nephrology-loving soul. This year’s dark horse is the Oxalate Offenders coming from the Green House conference. This underrated, but ever more identified, group has what it takes to make it all the way to the big dance.

Oxalate is an organic acid produced by plants for protection against hard ions such as calcium in high salinity groundwater. Plants may also use it for defence against infections and even from herbivores. Its poisonous nature was recognized when whole flocks of sheep perished after grazing in fields contaminated by Halogeton glomeratus. This plant contains up to 30% oxalate by weight and induces acute and chronic oxalate toxicosis in livestock. There are many other salt loving plants that are toxic in proportion to their oxalate content.

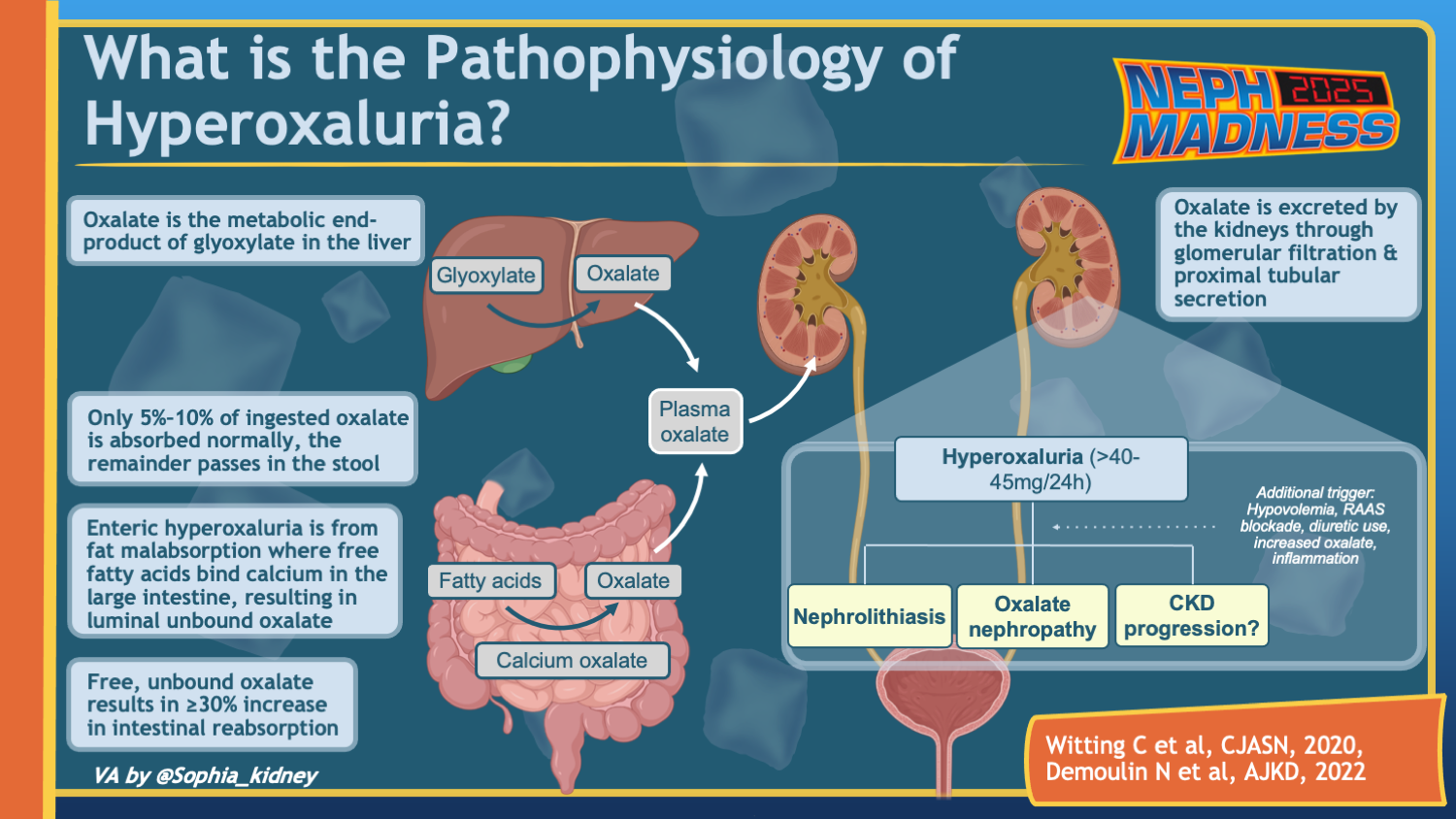

For humans, oxalate has no known nutritional benefit; it is, in fact, called an “anti-nutrient” by virtue of reducing calcium, iron, and magnesium absorption. Daily oxalate intake can vary widely, but the typical American diet supplies around 200 mg per day. Ten to 50% of that is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract. Soluble forms (Na and K oxalate salts) are absorbed best, but even insoluble Ca oxalate can be absorbed by an inflamed bowel. The main pathway for oxalate elimination is through the kidneys. Dietary hyperoxaluria is characterized by high levels of oxalate in urine (exceeding 40 mg/day). Certain gastrointestinal and genetic disorders can also make one prone to hyperoxaluria. This scouting report will focus on oxalate-rich plants that have the ability to bust everyone’s bracket this year.

The Oxalate Offenders have several veteran players who are household names. Leafy greens such as spinach and swiss chard, for instance. Spinach is one of the team’s strongest offenders with around 1000 mg of oxalate per 100 g serving. Nuts and seeds are another important category to consider. Almonds, cashews, and peanuts are the nuts with highest oxalate content. Several case reports have described patients developing oxalate nephropathy on a diet consisting mainly of nuts in the absence of any other predisposing conditions. Additionally, certain grains such as wheat bran and oats have high oxalate content and can wreak havoc on your kidneys if taken in excess. An important factor to consider when scouting this team is that the bioavailability of dietary oxalate is, in part, determined by the amount of calcium consumed, because calcium can bind to oxalate in the gut and decrease its absorption. Rhubarb stalks have a large amount of oxalate, coming in at about 800 mg per 100 g; rhubarb is one of the stronger players because of its low calcium content. With about 8 times as much oxalate as calcium, rhubarb has the ability to put up big numbers when needed. Rhubarb stalks are safe in moderation, but its leaves are inedible and have caused fatal poisonings. While most fruits have low to moderate amounts of oxalate, they can still cause damage if eaten in excess. For instance, take a look at this throwback to a humble guava. Star fruit (carambola) is in a class of its own, with up to 800 mg oxalate per 100g serving, and a neurotoxin called caramboxin adding to the toxidrome. As little as 25 ml of star fruit juice can be lethal to patients with decreased kidney function. Even without star fruit, the practice of “juicing” can be a problem, as it liquifies high oxalate produce (kiwi, spinach, beets) without adding milk (calcium), creating a perfect storm for oxalate absorption. As a nod to vitamins which otherwise don’t get to play in this year’s contest, let’s not forget the ability of high dose vitamin C to produce oxalate nephropathy and kidney stones by virtue of its metabolism to oxalate, and remind our patients with kidney disease to steer clear.

Key players and their stats can be seen below. Keep in mind that oxalate content in plants varies depending on growing conditions. Additionally, absorption from high-oxalate plants also depends on their calcium content. It is the highest when the oxalate to Ca ratio is >2 (plant group 1), and lowest when it is <1 (plant group 3).

Dietary hyperoxaluria causes crystalline nephropathy. Urine supersaturation with oxalate leads to precipitation of calcium oxalate crystals. Once formed, these can damage the kidneys in a few different ways. They can attach to the epithelial cells of the tubules and cause obstruction. They can also make way into the kidney interstitium and lead to inflammation and eventually fibrosis with renal function loss. Studies in animals show that inflammation induced by calcium oxalate crystals is mediated by NLRP3 inflammasome. Other types of crystal-induced inflammation, i.e. gout and atherosclerosis, borrow their offensive tactics from calcium oxalate. Studies in hyperoxaluric animals have shown an association between TGF-β released by NLRP3 and kidney fibrosis. This mechanism is supported by kidney biopsies in patients with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, known to cause excess oxalate absorption from the gut, demonstrated by widespread tubular injury, diffuse tubular calcium oxalate deposits, and varying degrees of tubulointerstitial scarring. High concentrations of oxalate were also shown to be directly cytotoxic in cultured renal tubular cells and animal studies.

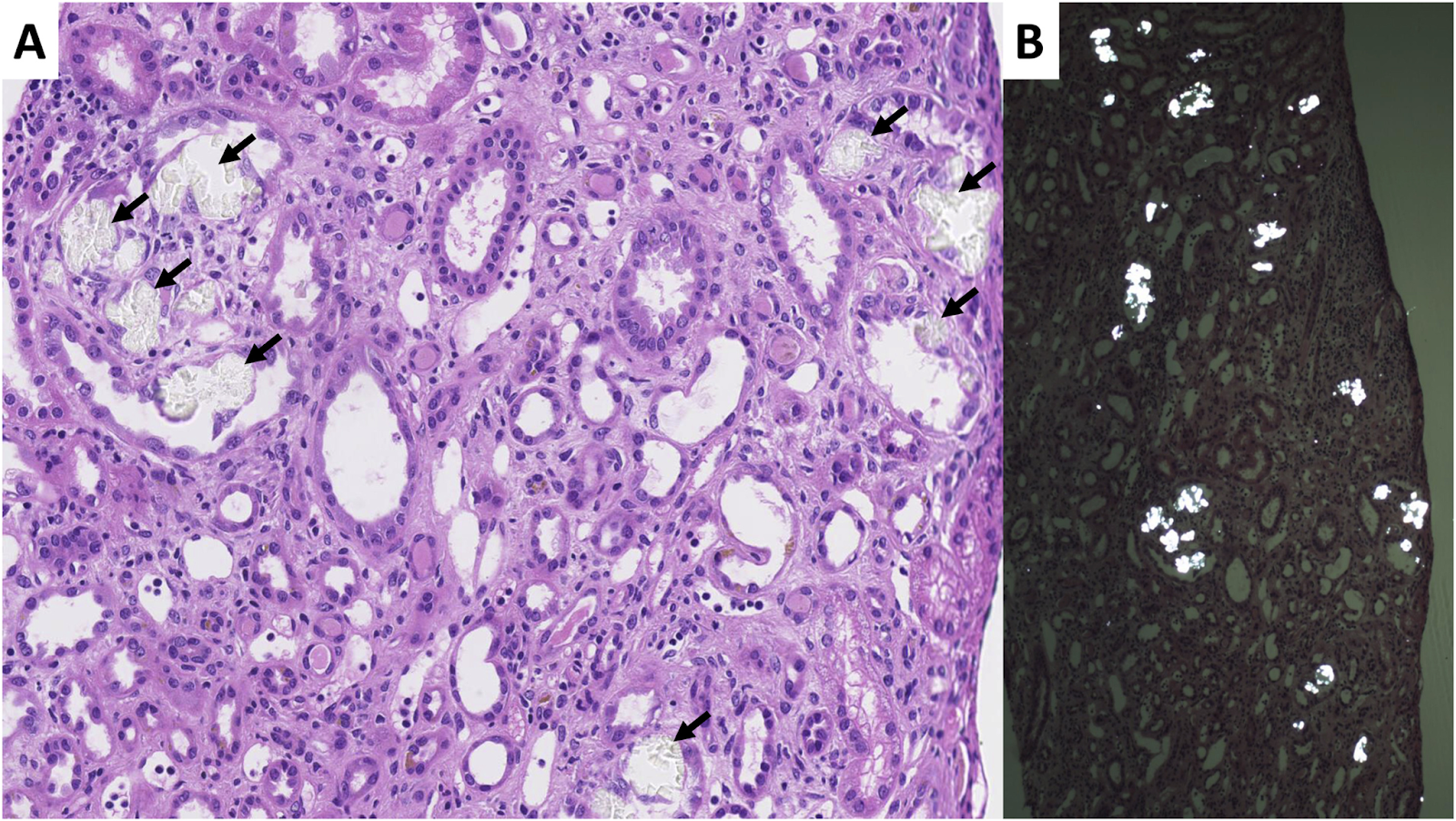

Oxalate nephropathy, kidney biopsy sample. (A) Intratubular translucent polyhedral or rhomboid crystals (black arrows) on light microscopy (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification, ×20). (B) Crystals shown are birefringent under polarized light (original magnification, ×5). Biopsy also shows acute tubular injury and mild interstitial inflammation. Fig 4 from Demoulin et al, © National Kidney Foundation.

Dietary hyperoxaluria can cause both acute and chronic kidney disease. In both forms you will find calcium oxalate crystals deposited in the tubular epithelial cells, tubular lumen, and less commonly, within the interstitium itself. These crystals will show birefringence under polarized light, and their demonstration is required to make the diagnosis of oxalate nephropathy. However, calcium oxalate deposition can also be an incidental finding on biopsy, especially in patients with decreased kidney function. For this reason, it has been suggested that an oxalate crystal to glomerulus ratio of 0.25 be added to the diagnostic criteria of oxalate nephropathy. In acute injury, biopsies show acute tubular necrosis, while both acute and chronic cases will reveal tubulointerstitial nephritis with a mononuclear cell infiltration. Chronic disease is characterized by varying levels of fibrosis within the interstitium. The clinical course depends on the hyperoxaluria’s onset and duration. An abrupt dietary oxalate overload leads to acute but typically reversible kidney damage. In contrast, long-term exposure causes chronic irreversible kidney disease.

Given that diet-induced oxalate nephropathy is rarely identified, no specific management guidelines have been developed. Current management recommendations are borrowed from treating other causes of hyperoxaluria and calcium oxalate kidney stones. Foremost in this category would be limiting foods rich in oxalate. Other recommendations include adequate dietary calcium intake to reduce oxalate absorption from the gut, increased fluid intake to reduce urinary concentration of oxalate, use of medications that can increase the urinary solubility of oxalate (such as potassium citrate), and some new strategies like enhancing intestinal metabolism with Oxalobacter formigenes products or oxalate decarboxylase, as well as using lanthanum carbonate as an oxalate binder in the gut. Both hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis can remove oxalate, but there are no guidelines for its use in secondary hyperoxaluria. Prognosis in dietary hyperoxaluria is mixed. Case studies of acute injury following high intake of oxalate–rich foods have shown favorable renal recovery with patients free of dialysis and with serum creatinine at or near their previous baseline. Reviews of all causes of secondary oxalate nephropathy have shown poor outcomes with half of patients requiring dialysis, although only a minority of the patients in the reviews had dietary hyperoxaluria.

Diet-induced oxalate nephropathy is a significant concern, highlighting the importance of being aware of dietary oxalate intake. Like free throws, it is something simple that should not be missed. Educating all patients, but most importantly those with predisposing conditions or a tendency to form kidney stones, is a proactive step you can take to decrease the likelihood of oxalate nephropathy and nephrolithiasis. Several studies have shown an association with elevated urinary oxalate levels and faster progression of chronic kidney disease. Don’t sleep on this under-the-radar, dark horse during this year’s games or in the future when you are evaluating the etiology of kidney stones and kidney disease!

– Executive Team Members for this region: Anna Vinnikova @KidneyWars – @kidneywars.bsky.social and Elena Cervantes @Elena_Cervants | Meet the Gamemakers

How to Claim CME and MOC

US-based physicians can earn 1.0 CME credit and 1.0 MOC per region through NKF PERC (detailed instructions here). The CME and MOC activity will expire on June 1, 2025.

Leave a Reply