Food and Kidney Disease

When the opening of a new Whole Foods Market in the Central West End in St. Louis was announced last year, most people who worked at Barnes-Jewish Hospital were excited to have a healthy option for lunch and grocery shopping within walking distance. I was personally much more excited to hear that maybe a Shake Shack would also be opening next door (which, unfortunately, turned out not to be true). As someone who does not normally do their food shopping at Whole Foods, I decided on a whim to stop by after work one day to pick up something healthy. In my limited experience shopping here, I usually end up spending three times what I expect. I purchased four apples and a loaf of bread which cost me just over $12.

In stark contrast to the organic apples and grass-fed beef at Whole Foods, there is a McDonald’s just around the corner on Lindell Boulevard. In full disclosure, I frequented this place many times during my med school years. My budget was tight, my time was valuable, and the draw of a quick and inexpensive meal outweighed the potential detriments to my health. For the same $12, I could buy dinner for my whole family.

The issue of this food disparity is brought up by two articles recently published in AJKD. America is undoubtedly going through an obesity epidemic. One in three adults is obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2), and this contributes significantly to the growing incidence of diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). The obesity epidemic is particularly true in the end-stage renal disease (ESRD) population, as the increasing BMI trend in patients initiating dialysis outpace age-matched controls. Targeting obesity is arguably one of the most modifiable risk factors for prevention of the development of CKD and a patient’s general health.

What are the causative factors contributing to this alarming trend? Kramer lists the following in her recent AJKD article:

Cartoon depicts the imbalance in acid-producing foods (meats, cereals, and grains) and foods yielding alkali (fruits and vegetables) in the Western diet. Figure 4 from Holly Kramer, AJKD © National Kidney Foundation.

- The average daily caloric intake in the US has increased by approximately 530 calories between 1970 and 2000

- Food has become particularly inexpensive due to industrialization and processing – families now spend less than 20% of their total income on food (compared to 40% fifty years ago)

- High salt, increased animal protein, and decreased intake of fruits/vegetables characterize food as a result of industrialization may contribute to the development of CKD via hemodynamic effects (afferent arteriolar vasodilation) and acid-base imbalance (increased daily acid load)

The first two issues (increased calories and food industrialization leading to inexpensive, processed food) go hand in hand. Let’s address the dietary factors in the 3rd point individually.

Sodium intake is well-known to be a contributor to the development of hypertension with age. Data from the INTERSALT study show that populations with a very low salt intake (for example, the Yanomamo Indians from the Amazon basin averaged 1 mEq of sodium intake/day, mean systolic BP 90) have lower incidences of hypertension. Contrast this with the Akita prefecture in Japan, where the mean daily sodium intake of 462 mEq correlates with much higher incidences of hypertension. Investigators identified this high sodium intake was a result of pickled vegetables, miso, and soy sauce. Similar sodium levels can be found in highly processed meats and canned vegetables/soups in a low-income Western diet. Indeed, Kramer points out that processed foods now account for the majority of sodium intake due to the industrialization of the US diet, with table salt accounting for less than 10% of total salt consumption. Animal models have shown that high salt intake at these levels amplifies glomerular hypertrophy and upregulates fibrotic growth factors.

Excess protein intake and a decrease in fruits and vegetables is another factor that may contribute to CKD. The typical US diet contains about twice the protein intake recommended by US dietary guidelines (0.8 g/kg/day). Additionally, the main source of this excess is animal protein. High animal protein intake has many adverse effects on glomerular hemodynamics, including increased renal blood flow, hyperfiltration, and intraglomerular hypertension. Interestingly, these changes are not associated with vegetable protein intake. Furthermore, this protein imbalance leads to excess production of nonvolatile acids, which have independent adverse effects on bone health and muscle catabolism.

Meanwhile, the AJKD paper by Banerjee et al discusses the issue of food security and access to healthy dietary options. Food security is defined as one’s perceived ability to access nutritious and healthy food with essential nutrients, fruits, and vegetables, and with less saturated fats, sugar, and salt for an active healthy life. In 2013, 14.3% of American households were categorized as food insecure. These households with limited resources stretch their budgets by purchasing cheap, energy-dense, and nutrient-poor foods such as refined grains, added sugars, and saturated and trans fats. They consume fewer servings of fruits, vegetables, and dairy products.

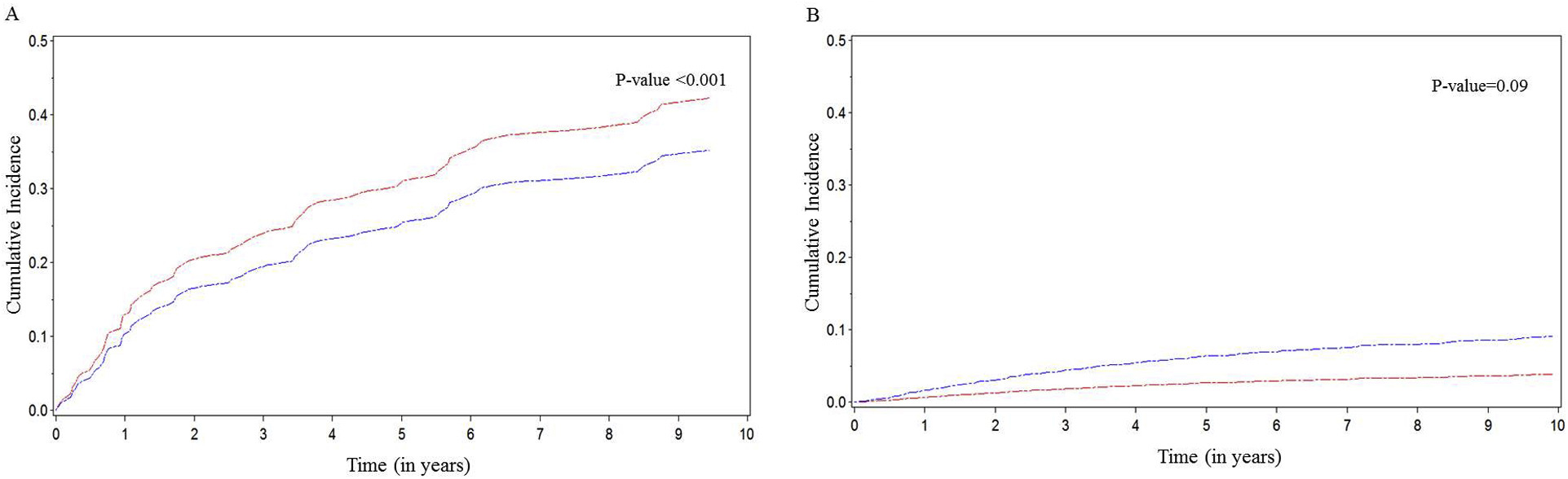

Cumulative incidence for risk for end-stage renal disease by food insecurity status in the (A) chronic kidney disease (CKD) group and (B) non-CKD group. Red line, food-insecure group; blue line, food secure group. Figure 1 from Banerjee et al, AJKD © National Kidney Foundation.

Using data from the NHANES III CKD cohort, Banerjee et al identified that food insecurity (defined by whether the subjects ever thought they did not have enough money to eat what they would like to eat) was associated with a higher likelihood of developing ESRD independent of demographics and clinical risk factors. Interestingly, adults without CKD showed no association between food insecurity and incident ESRD. Clinicians should be aware that this nontraditional risk factor of food insecurity due to relative poverty is present in lower income individuals and can contribute to progression of CKD. This issue poses a public health threat that can be addressed by better detection and early dietary intervention.

Photo: 123rf / lightwise

Clinicians often advise lifestyle changes including exercise and a healthy diet. However, we should also be aware of the struggle that many lower income patients may encounter when dealing with food security. The “Whole Foods vs. McDonald’s” scenario is very real, and understanding this from the patient perspective can help us to target their individual situation.

Post prepared by Timothy Yau, AJKD Social Media Editor. Follow him @Maximal_Change.

To view the Kramer article full-text (freely available), please visit AJKD.org.

To view the Banerjee et al article abstract or full-text (subscription required), please visit AJKD.org.

If DM and HTN are the most common causes of CKD, then “Targeting obesity is arguably one of the most modifiable risk factors for prevention of the development of CKD and a patient’s general health” is an understatement. CKD and nephrology are completely different without the society creation of obesity.