Nephrologists’ Perspectives on Discussing Conservative Management in CKD: A Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative research is a broad methodological approach that uses non-numerical data to understand an individual’s knowledge, motivations, and attitudes toward a problem. If performed rigorously, qualitative research in healthcare can inform future studies geared towards issues that patients and stakeholders explicitly identify as important. For this reason, qualitative analyses lend themselves nicely to exploring patient and provider attitudes towards nuanced treatment considerations, such as discussing advance care planning in kidney disease.

Despite the existence of guidelines to help facilitate conversations based on a framework of shared decision-making, kidney patients continue to cite a lack of prognostic information provided to them by their nephrologists and still seek more detailed conversations regarding their goals of care. Prior studies have pointed to a lack of communication-skills training, expectations for aggressive care among non-nephrologists, fear of evoking negative reactions among patients, and unfortunately even financial incentives to dialyze as examples of provider and systems-level barriers that hinder these dialogues.

To further characterize barriers, identify facilitators, and pinpoint catalysts in discussing conservative management with older patients with chronic kidney disease, Ladin et al conducted a series of semi-structured interviews of 35 US nephrologists and present their data in AJKD.

The authors used a literature review followed by deliberate sampling methods to stratify their analyses by factors which were thought to influence provider comfort with discussing conservative management: gender, years in nephrology practice, practice type, and geographical region. The authors also thoughtfully allowed some physicians to recommend additional nephrologists at their institution for participation, so as to help uncover any institutional patterns in advance care planning practices.

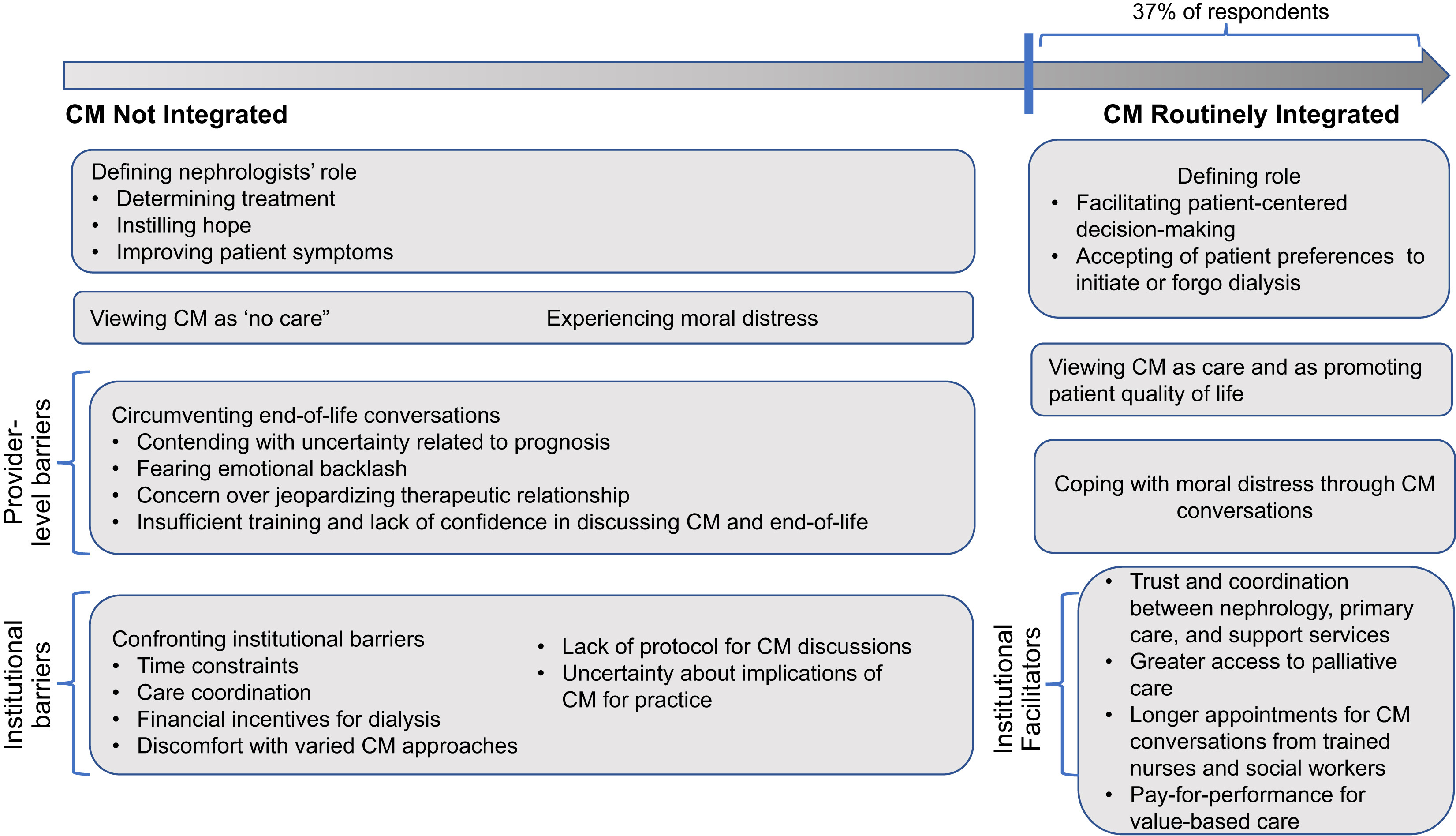

Of the nephrologists interviewed, 80% were from academic medical centers, 66% had been practicing for over 10 years, and 20% were women. Only 37% of all nephrologists who were interviewed reported routinely discussing conservative management. After audio transcripts were transcribed, coded, and analyzed for thematic saturation, five key premises emerged:

- struggling to define one’s role

- fearing the endangerment of the patient-provider relationship

- confronting institutional barriers

- struggling with considering conservative management as distinct from “no care”

- experiencing ethical distress

These themes, as well as their representative quotations, are briefly outlined below:

Struggling to define roles

“I view myself as someone who tries to provide a ray of hope for people who are sick… I’ve seen enough people who feel so much better [after dialysis]…”

Ladin et al’s analysis revealed that role perceptions were highly influential in determining whether a nephrologist was likely to discuss conservative management. Some nephrologists took a more active role in formulating their patients’ care plans, often urging dialysis despite initial hesitation from their patients. Others tried to honor patient wishes at all costs, even when those wishes were at complete odds with provider preference. Some nephrologists felt primarily responsible for giving their patients hope and feared that discussing conservative management would provoke despair. Nephrologists who self-identified in this category often chose to forgo disclosing in-depth details about patient prognosis.

Managing prognostic uncertainty and endangering the patient-provider relationship

“We are really, as a profession…so terrible at prognosis… To some extent it’s false optimism and… unwillingness to face death…[and] also the realization that we’re just so terrible at predicting the future…”

Many nephrologists admitted to circumventing advance care planning conversations in favor of more objective terms directly related to the patient’s renal function. Providers cited prognostic uncertainty and a deep reluctance to upset patients’ emotional wellbeing. A common underlying theme involved a fear of jeopardizing carefully-cultivated longitudinal patient relationships.

Confronting institutional barriers

“We… talk about quality of life to the patients, we try to gauge what is important for them, but I do believe we do a poor job because of the limits of time….”

Conservative management discussions were significantly hindered by a perceived lack of care coordination and time constraints. Some nephrologists felt unsupported by their healthcare system and overwhelmed with trying to independently establish conservative care plans for their patients. Many providers expressed a desire for assistance from palliative care colleagues and social workers to facilitate a comprehensive, team-based approach.

Reframing conservative management as distinct from “no care”

“[We are] comfortable ourselves with the fact that we’re in the business of combatting death. But we need to become [better] with the business of accepting death… that we have limits.”

Several nephrologists likened conservative management to a “withdrawal of care.” They struggled with not being able to provide patients with what they felt were more “active” steps in a care plan, such as placement of dialysis access or referral to transplant surgery. Many providers equated conservative management with imminent death.

Coping with moral distress

“I’ve noticed… several of my older colleagues… have far less trouble in saying, ‘This is enough…there’s no quality of life here, there’s no chance of any meaningful recovery, why are we flogging this poor person?’ Whereas my younger colleagues are fighting to the bitter end.”

A provider’s experience of moral distress emerged as predictive of his or her willingness to discuss conservative management. Those nephrologists who initiated advance care planning earlier in a patient’s treatment course expressed a decrease in moral distress, whereas as those who delayed these conversations suffered from increased frustration and anxiety. As outlined by the quotation above, age (and undoubtedly, length of time in nephrology practice) seemed to also play a role in willingness to engage in early conservative management discussions.

Factors influencing nephrologists’ decisions to discuss conservative management (CM). This schematic presents the spectrum of integration of CM into care discussions, spanning from no integration of CM to routine integration of CM. The boxes are derived from the thematic analysis and convey barriers and facilitators affecting nephrologists’ decision to present CM and factors affecting how they approach care discussions. Figure 1 from Ladin et al, AJKD © National Kidney Foundation.

Discussing conservative management has been recognized by both seasoned nephrologists as well as early trainees to be a requisite part of patient-centered care, yet many barriers remain. The results of this study by Ladin et al are reminiscent of those in Sellars et al’s analysis from Australia, which highlighted provider discomfort in negotiating moral boundaries, navigating vulnerable conversations, and clarifying roles in advance care planning.

What are some steps that can be taken to help address these barriers? Institutional culture should emphasize and prioritize advance care planning as a routine part of outpatient nephrology care; however, part of the issue may be the way these conversations are framed. Patients naturally gravitate towards treatments that are described in an active, rather than passive manner. Conversations should occur over multiple visits and ideally involve the valuable input of social workers, psychologists, dietitians, and palliative care consultants. An interprofessional approach makes broaching these hard conversation more manageable as a team. Nephrologists must continue to develop and familiarize themselves with risk prediction models for kidney disease progression, and gain comfort in having end-of-life discussions through communication-skills training and education. Ultimately, care should be taken to distinguish “withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies” from “withdrawal of care,” of which the latter should technically never occur in a patient’s treatment plan.

It should be emphasized that the nephrologists in these interviews who admitted to circumventing conversations regarding advance care planning were still acting in what they felt were their patients’ best interests. But these and other qualitative studies demonstrate that if we continue to avoid having potentially uncomfortable conversations with our patients, we sacrifice transparency, diminish trust, and ultimately, do them no favors.

– Post written by Devika Nair (@devimol), AJKDBlog Fellow Contributor

To view Ladin et al (subscription required), please visit AJKD.org.

Title: Discussing Conservative Management With Older Patients With CKD: An Interview Study of Nephrologists

Authors: K. Ladin, R. Pandya, A. Kannam, R. Loke, T. Oskoui, R.D. Perrone, K.B. Meyer, D.E. Weiner, and J.B. Wong

DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.11.011

Leave a Reply