#NephMadness 2024: Peritoneal Dialysis Region

Submit your picks! | NephMadness 2024 | #NephMadness

Selection Committee Member: Janice Lea

Dr. Janice P. Lea is a Professor of Medicine at Emory University and is board-certified in Nephrology and Hypertension. Dr. Lea is the Clinical Director of Nephrology and of Telenephrology as well as Chief Medical Director of Emory Dialysis, including Home Dialysis therapies. She earned her medical degree at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston and completed her residency in Internal Medicine and a Nephrology fellowship at Emory. Dr. Lea’s research and clinical expertise are in hypertension, CKD, kidney health disparities, and in dialysis outcomes.

Selection Committee Member: Jeff Perl @PD_Perls

Dr. Jeffrey Perl is a staff nephrologist at St Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and Associate Professor of Medicine at the University of Toronto. His primary research interests, clinical practice, and teaching focuses on improving universal access to and clinical outcomes of home dialysis. Dr. Perl is Editor-in-Chief of Peritoneal Dialysis International and recently co-chaired the KDIGO Home Dialysis Controversies Conference.

Writer: Timothy Hopper

Dr Timothy Hopper is a second-year nephrology fellow at Duke University. He will be joining the Duke Nephrology faculty next year and looks forward to pursuing his interests in APOL1-mediated kidney disease, home dialysis modalities, and medical education.

Competitors for the Peritoneal Dialysis Region

Team 1: PD First

versus

Team 2: Beyond Kt/V

Image generated by Evan Zeitler using Image Creator from Microsoft Designer, accessed via https://www.bing.com/images/create, January, 2024. After using the tool to generate the image, Zeitler and the NephMadness Executive Team reviewed and take full responsibility for the final graphic image.

Team 1:

PD First

Copyright: Phawat/Shutterstock

As anyone who has ever seen a post-game March Madness interview can attest, a winning strategy is all about working as a team, having the right game plan, and then executing. For PD First to win it all, they’ll need to play with urgency and focus on scoring points in transition.

“Sometimes you make up your mind about something without knowing why, and your decision persists by the power of inertia. Every year it gets harder to change.”

― Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Introduction

In 2001, the National Pre-ESRD Education Initiative—the largest study of its kind to date—showed that among patients who receive thorough pre-kidney failure education about kidney replacement modalities, around 45% choose peritoneal dialysis (PD) as their preferred dialysis treatment. When nephrologists are asked what informs their decision-making on dialysis modality selection, they rate patient preference as the most important factor, followed by quality of life and morbidity. However, according to the USRDS ESRD database, as of 2021 only 13% of patients starting dialysis are initiated on PD.

In other parts of the world, rates of PD use are notably higher. In Hong Kong as of 2012, 79% of their dialysis population was using PD; in Mexico, about 66% of all patients receiving dialysis were on PD.

The chasm between patient’s preferred modality and what they actually receive is an issue that has risen to the forefront of nephrology in recent years. Financial incentives introduced in the End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices (ETC) payment model in 2021 have yielded a small but statistically significant increase in patients initiating home dialysis, compared with patients in non-ETC markets. Overall, rates of home dialysis use have been increasing in the US from 10% in 2016 to 17.4% in 2022. However, we remain well short of the bold aspirations of the Advancing American Kidney Health (AAKH) initiative, announced in 2019, which aims to have 80% of new patients with kidney failure receiving home dialysis therapies or transplant by the year 2025.

To make progress towards these worthwhile goals, we need new approaches to pre-kidney failure education, changes to the structure of outpatient dialysis units, and continued evolution towards value-based care. Peritoneal dialysis enhances patient autonomy, is associated with relative preservation of residual kidney function (RKF) compared to other therapies, and saves money for the health care system. We must continue to innovate to find new ways to provide PD first!

The Unplanned Start

The archnemesis of the “PD First” approach is the “unplanned start,” where patients are admitted to the hospital with an urgent dialysis indication and often have to start dialyzing via a central venous catheter. It is typically challenging to obtain a PD catheter in this timeframe, and even if it were, many inpatient services are not set up to provide the requisite training for patients to start PD in the inpatient setting. For patients with acute kidney injury, this situation may be difficult to avoid, but for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), the unplanned start is often preventable. One obvious concern is that CKD is underdiagnosed. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 40% of individuals with severely reduced kidney function are unaware of the diagnosis. However, even among patients with timely referral to nephrology, the majority still have a suboptimal start.

Many patients with CKD prefer to wait as long as possible to start dialysis, often underappreciating their uremic symptoms, and their nephrologists may go along with this due to high-quality evidence suggesting that late starts do not affect mortality in HD. However, unplanned starts expose patients to unnecessary hospitalization, often require central venous catheters with higher infection risks, and prevent many patients from starting on their preferred dialysis technique

Incremental PD

Starting with incremental PD—a less-intensive PD approach that factors in a patient’s RKF—mitigates the change to patients’ lifestyles while helping them safely navigate the transition from stage 5 CKD to dialysis-dependence. Incremental PD encompasses a wide range of approaches that may include fewer exchanges, smaller volumes, dialyzing less than 7 days per week, and/or less total dwell time. It can be as simple as doing a single long dwell with icodextrin overnight. Starting with a less onerous prescription is particularly important in light of the fact that one large retrospective cohort of more than 16,000 PD patients showed that over 10% of the cases of PD discontinuation within the first year were attributed to either psychosocial issues or patient preference.

Importantly, incremental PD does not imply early initiation of dialysis; it is initiated at the same time as full-dose PD. When RKF declines, the prescription is intensified accordingly. Early data suggests that doing fewer exchanges early on results in fewer episodes of peritonitis. Furthermore, since hypertonic glucose exposure over time often leads to membrane failure, minimizing glucose exposure in the early stages prolongs the viability of the peritoneal membrane for PD. Furthermore, there are obvious financial and environmental benefits to judicious use of PD fluid.

In order to successfully partner with patients to provide high-quality incremental PD, it is crucial to set expectations appropriately. Patients should understand that as their RKF declines, it is expected that they will require more intensive PD. Understandably, patients may be reluctant to increase their treatment time later on. However, this challenge should be met with open dialogue and education on the rationale for increasing the prescription. In light of the risks of accumulated glucose exposure over time, it is not appropriate to give a more intensive regimen than the patient needs from the outset for the sake of expediency. Providing the required amount of PD to meet a patient’s needs should be the standard of care. When a patient has significant RKF, incremental PD is an excellent option.

Urgent Start PD

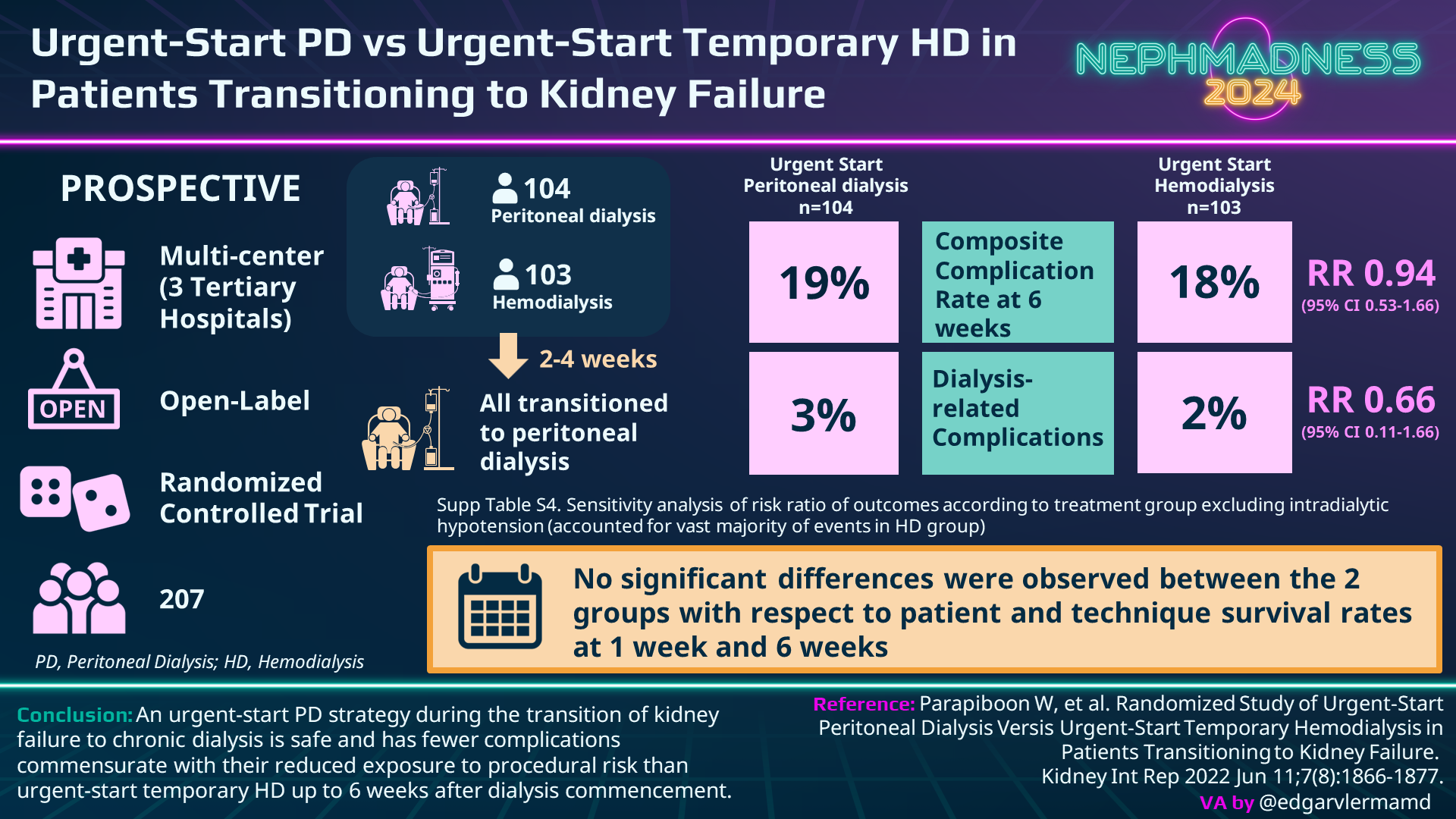

In unstable patients, such as those with severe uremia, pulmonary edema, or hyperkalemia, urgent initiation of hemodialysis may be unavoidable and necessary to remove toxins, remove fluid, or regulate electrolytes. However, a large share of patients admitted to the hospital for dialysis initiation could be medically managed for a few days. They just can’t necessarily wait several weeks. Though high-quality evidence is lacking, numerous observational studies comparing urgent start PD with HD suggest lower rates of bacteremia in urgent start PD due to reduced utilization of central venous catheters. One recent randomized trial comparing urgent start PD to urgent start HD showed a lower composite complication rate in the PD group (19% versus 37%, RR 0.52) but no significant differences in patient and technique survival at six weeks. Most of the events in the HD group were from intradialytic hypotension. When you remove this group the adverse events are identical (19% versus 18%).

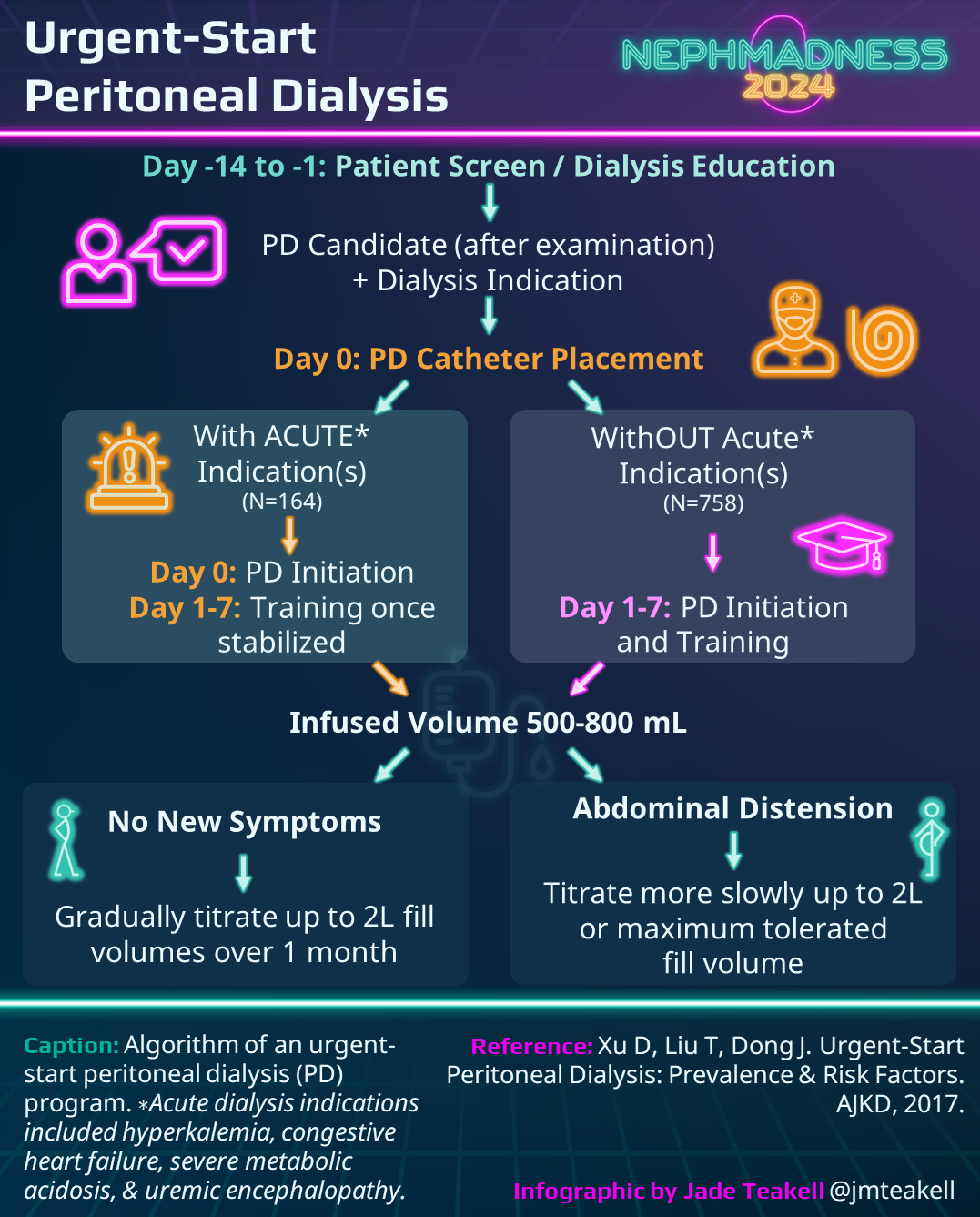

Furthermore, according to a 2020 Cochrane review comparing urgent start PD with conventional PD, the only significant difference between the groups was a higher rate of dialysate leaks (RR 3.9, 95% CI 1.56-9.78) in the urgent start group. These leaks can usually be managed conservatively and typically do not require catheter replacement or change of modality. The risk of catheter leaks can be mitigated by starting with low dialysate volumes (750mL to 1250 mL depending on patient size), having the patient lie in a recumbent position, ensuring adequate bowel regimen, and providing cough suppressants when needed—all of which help to maintain low intra-abdominal pressure. These strategies are particularly crucial during the first couple weeks of treatment. Surgeons can also help decrease the risk of PD catheter leaks by placing the deep cuff in the rectus muscle and using a purse string suture at the deep cuff.

In order to facilitate urgent-start PD, a program must have the ability to obtain timely PD catheter placement, ideally within 48 hours, and a willingness to use these catheters shortly after placement. There needs to be a rigorous process for identifying appropriate candidates and robust administrative and staffing support for urgent-start PD in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Implementation of protocols for inpatient and outpatient urgent-start PD is highly recommended.

PD Catheter Placement Timing

The ability to implement PD first requires obtaining access in a timely manner. Having a surgeon available to place a PD catheter within 48 hours of determining the need to start dialysis is a tall order. Furthermore, the International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) generally recommends waiting at least 2 weeks to use a PD catheter after implantation in order to optimize surgical site healing and decrease the risk of leaks, though the guidelines note that is possible to start as soon as the same day with low volume exchanges.

To optimize healing prior to PD initiation, the Moncrief-Popovich technique, first described in 1993, involves tunneling the free end of the catheter into subcutaneous fat for at least 4 weeks before making a small skin incision to exteriorize the PD catheter. This embedded PD catheter approach has gained popularity with the renewed focus on PD first. Though there is a lack of high-quality evidence comparing outcomes with embedded and non-embedded PD catheters, retrospective cohort data indicates a lower rate of catheter-related infections with embedded catheters despite a trend towards higher risk of primary non-function. In addition to avoiding the logistical hassle of coordinating an urgent surgery, embedded catheters have the benefit of being ready to use the moment a patient has an indication to start PD.

Patient and Provider Education

Winning isn’t all about starting strong; it’s also about picking the right players and having a game plan that plays to each individual’s strengths. Traditionally, nephrologists have limited the pool of patients considered for PD based on a variety of concerns, ranging from high BMI to lack of residual kidney function, or even low social support. In order to approach the home dialysis goals put forth in the Advancing American Kidney Health (AAKH) initiative, nephrologists will need to employ peritoneal dialysis across a wider spectrum of patients.

Though there are many factors to consider in determining the most appropriate dialysis strategy, there are few absolute contraindications to PD. Severe intraperitoneal adhesions, leaks in the peritoneal membrane that cannot be fixed, and hernias that are not amenable to repair would all fall into this category. However, one should not assume that a patient who has had multiple abdominal surgeries is going to have adhesions or that a leak or hernia cannot be repaired unless the patient has been through a rigorous surgical evaluation. A recent multicenter study of 758 individuals in the US and Canada who underwent laparoscopic PD catheter insertion showed that, of the 201 patients who were found to have adhesions, only 17% experienced the primary composite outcome–which included inability to start PD, PD discontinuation, or the need for invasive procedures due to catheter flow issues or abdominal pain–within 6 months of PD catheter placement. By comparison, 10% of the patients in the no adhesion group reached the primary composite outcome (HR 1.64; 95% CI 1.05-2.55). While the overall catheter-related complications were modestly higher in the adhesions group, it is notable that 83% of the patients with adhesions did not experience PD catheter-related complications in the first 6 months. Furthermore, the majority of the patients who required invasive procedures did not have to discontinue PD.

There are numerous co-morbid conditions that are less than ideal for PD but are not contraindications. For instance, despite their immunosuppressed state, liver transplant patients have tolerated PD with similar rates of infection and overall survival compared with non-transplant patients. Morbidly obese patients and patients with ostomies can safely undergo peritoneal dialysis, often with the aid of a presternal catheter. Patients with polycystic kidney disease are often able to tolerate frequent, low-volume exchanges.

While it is crucial that PD is performed in a sterile environment by someone who is capable and reliable, nephrologists should be wary of excluding patients from PD due to perceptions of poor social support, low health literacy, or even cognitive impairment. A robust education program can overcome knowledge deficits, and a caregiver can assist with PD for those who are physically or mentally unable to perform it themselves.

As with most important healthcare decisions, the choice of dialysis modality should be shared between nephrologists and their patients. Before this choice is made, patients should be disabused of any biased notions about PD that they may have heard from providers in the past, i.e. “Your PD catheter is going to get infected” or “It’s way too much work.” Even if there are potential barriers to success, patients and families should be well-informed about the risks and benefits of PD and given the opportunity to try to address those challenges.

Check out this podcast episode of PD Exchange featuring Jeff Perl, Nikhil Shah, Matt Sparks, and Tim Hopper:

#NephMadness and the Peritoneal Dialysis : Cage match!

Team 2:

Beyond Kt/V

Copyright: Canities/Shutterstock

Like the addition of the three-point line in basketball, the invention of Kt/V changed the game in nephrology. With the ability to calculate clearance, nephrologists, who are known to be somewhat numerically inclined, tailored their dialysis prescriptions and started putting up all-star Kt/V numbers. However, focusing too much on one aspect of the game, whether it’s shooting too many three-pointers or over-emphasizing Kt/V, can lead to bad outcomes. The International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) captured this insight in their 2020 guidelines by shifting focus away from achieving “adequacy” in terms of small solute removal and instead prioritizing the patient’s life goals and “the provision of high-quality care by the dialysis team.”

“Stephen [Curry]’s explosiveness and athleticism are below standard… He will have limited success at the next level. Do not rely on him to run your team.”

– An NBA Scouting Report on Steph Curry, 2009

Kt/V: A Historical Perspective

One of the seminal studies of PD “adequacy” was CANUSA, a prospective cohort study of 680 patients in the US and Canada who started continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD) from 1990-1992. The results seemed to suggest that higher weekly Kt/V was associated with lower mortality. In that study, a weekly Kt/V of 2.1 corresponded to 78% two-year survival. Each decrease of 0.1 units in weekly Kt/V yielded a 5% increase in the relative risk of death. Around the same time, a small Italian study (n = 68 CAPD patients) suggested that weekly Kt/Vurea of at least 1.96 “was associated with definitively better survival.” As a result of these studies, the 1997 NKF-Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative clinical practice guidelines endorsed a weekly Kt/Vurea target of at least 2.0.

More robust randomized controlled trials, such as the ADEMEX study, however, did not reproduce these dose-dependent benefits. In ADEMEX, 965 CAPD patients were randomized to target either intensive PD with average Kt/V of 2.27 or standard PD with average Kt/V of 1.80. There were no survival differences whatsoever between the two groups. A subsequent re-analysis of CANUSA showed that the supposed benefit of the higher Kt/V was actually driven by underlying residual kidney function (RKF). Thus, the 2006 ISPD guidelines decreased the minimum threshold Kt/V to 1.7, where it has remained since then.

Kt/V: The Good and the Bad

On the positive side, measuring Kt/V is affordable and not too onerous. In PD, since the effluent fluid is close to 100% saturated, one can estimate Kt/V with only a patient’s total dialysate volume and total body water (TBW), which represents the volume of distribution (V) of urea. It is more rigorously measured every 3-6 months, when patients do a 24-hour urine collection to measure clearance from RKF and bring in a dialysate sample. Declines in Kt/V can often suggest a decline in RKF but can also reflect changes in peritoneal membrane function, akin to the way a sudden decrease in Kt/V in hemodialysis might indicate a vascular access problem.

However, Kt/V also has some significant limitations. First of all, there is no compelling evidence that a weekly Kt/V of at least 1.7 in PD affects overall survival. A Hong Kong randomized clinical trial of 320 CAPD patients, split into groups targeting Kt/V 1.5-1.7, 1.7-2.0, and >2.0 found “no significant differences in patient survival, hospitalization rate, or serum albumin among the three groups after 2 years,” though the Kt/V 1.5-1.7 group did require more erythropoietin treatment. Furthermore, while BUN is often thought of as a surrogate for the so-called “middle-weight molecules” that are felt to cause uremia, there is no high-quality evidence linking Kt/Vurea to control of uremic symptoms. After all, clearance of these larger molecules is more dwell-time dependent due to their lower membrane permeability. In many patients, particularly at the extremes of BMI, estimates of TBW can be inaccurate. Since urea is not very soluble in adipose tissue, using body weight to calculate TBW in obese patients may give a falsely high estimate of the volume of distribution of urea and artificially lower the Kt/V. It may not be practical or appropriate to reach a Kt/V of 1.7 in this group.

Some PD experts advocate eliminating the measurement of Kt/V entirely because it does not have a clear impact on patient outcomes. Others consider Kt/V a useful measurement of small solute clearance that can call attention to changes in RKF or peritoneal membrane characteristics. Regardless of one’s perspective on Kt/V monitoring, there is no evidence to support that high-quality PD has a minimal Kt/V threshold. As a result, the ISPD has concluded that the traditional focus on achieving a weekly Kt/V of at least 1.7 has been misplaced.

Assessing High-Quality PD: The Way Forward

The 2020 ISPD guidelines emphasize the importance of shared decision-making to help patients achieve their life goals. The SONG-PD study group surveyed PD patients and their caregivers to determine their priorities. They reported their most important outcomes as infection, mortality, fatigue, and flexibility with time. Patients and caregivers rate dialysis solute clearance 52nd out of 56 categories on their list of priorities, suggesting that they find the kinetics of solute transport across the peritoneal membrane somewhat less interesting than the average nephrologist. Nephrologists should discuss the trade-offs among these priorities (i.e. lengthening the treatment time to decrease fatigue and improve clearance) to craft a PD prescription that is tailored to the individual.

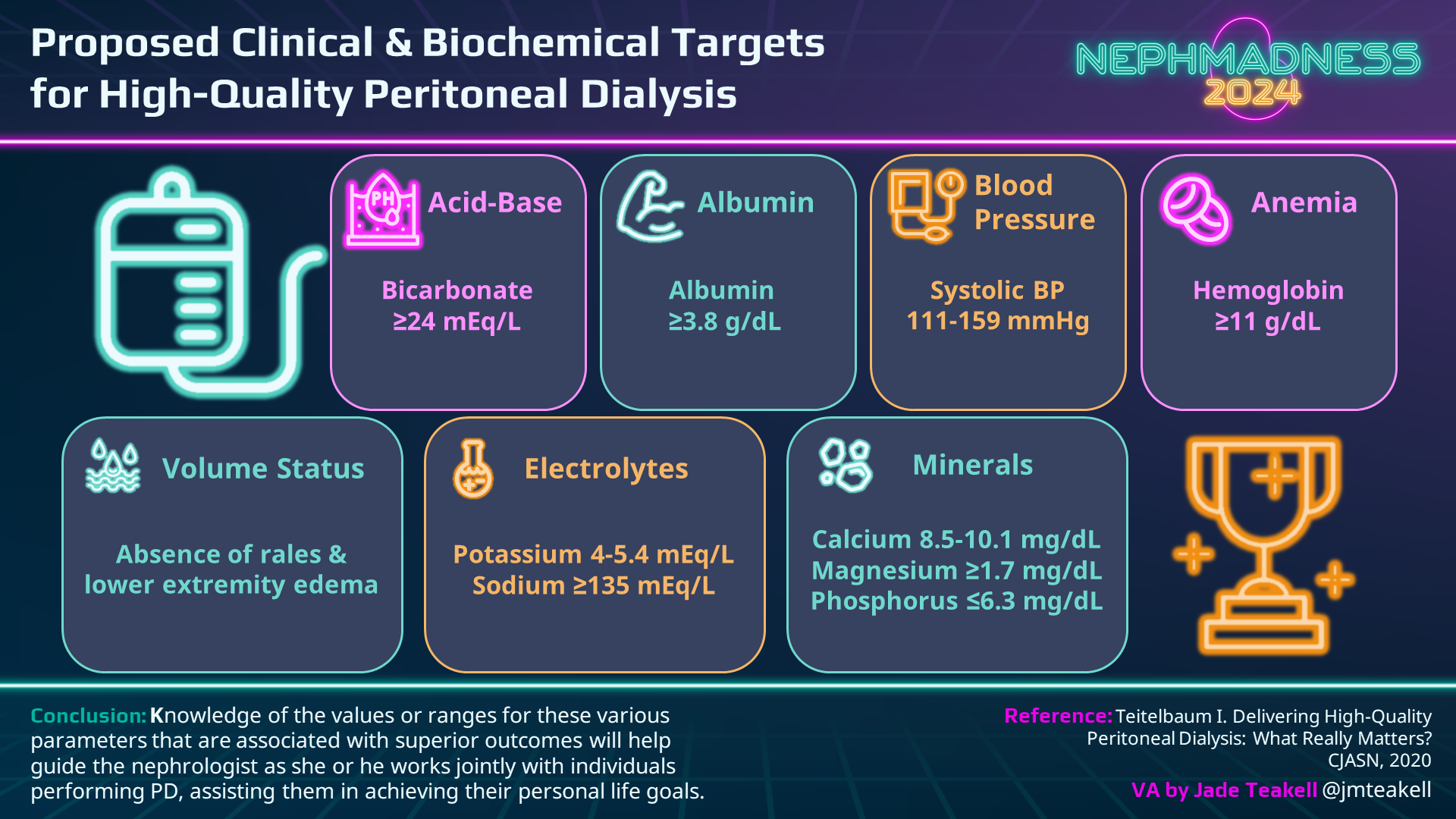

The second imperative of the 2020 ISPD guidelines is to provide high-quality care. The question of how to measure performance remains challenging, and like many questions in nephrology, the answer is multifactorial. One obvious way to measure high-quality care is to ask patients directly how they are doing via the assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) scores; the crucial influences of other co-morbidities and social circumstances are drawbacks of this approach. Additionally, this type of subjective questionnaire can be biased, particularly when the provider team has a vested interest in achieving good outcomes. In terms of more objective measures, PD expert Dr. Isaac Teitelbaum advocates targeting specific parameters.

The 2020 ISPD guidelines also note that for those with limited life expectancy or who are extremely frail, it may be appropriate to reduce the PD prescription to lower treatment burden, even if it may compromise some of the other objective parameters.

In summary, to reach the goals of the 2019 AAKH initiative, nephrologists must find ways to bring PD to a wider population of patients. We will need to partner with patients to educate them about PD and help them overcome barriers to make it possible. Once they are on PD, we will need to prescribe PD in a way that optimizes patient priorities and minimizes the risk of PD discontinuation. We have moved past the era of targeting “adequate” PD that achieves a weekly Kt/V of 1.7. Moving forward, the goal of PD therapy will be to optimize the outcomes that truly matter: the overall health and well-being of our patients.

COMMENTARY BY OSAMA EL SHAMY:

Adjusting “Quality” versus Quantity in Peritoneal Dialysis

– Executive Team Members for this region: Matthew Sparks @Nephro_Sparks and Jeff Kott @jrkott27 | Meet the Gamemakers

How to Claim CME and MOC

US-based physicians can earn 1.0 CME credit and 1.0 MOC per region through NKF PERC (detailed instructions here). The CME and MOC activity will expire on May 31, 2024.

Submit your picks! | #NephMadness | @NephMadness

Leave a Reply