The Continued Importance of Qualitative Research in Kidney Disease

Qualitative data has been increasingly used to help illustrate the illness experiences of patients with dialysis-dependent kidney disease. Examples include studies detailing patients’ attitudes towards conservative management, experiences while waiting for a transplant, and difficulties with medication adherence. Fewer studies have focused on patients with pre-dialysis kidney disease, particularly with regards to their experiences adjusting to an often poorly-understood illness.

In a recent meta-ethnographic review published in AJKD, Teasdale et al summarized and interpreted existing qualitative studies which outlined patients’ experiences after having received a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Their final analysis included ten studies from seven countries and collectively represented the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of 596 patients.

Key themes identified by the authors and potential areas for future research are discussed below:

A challenging diagnosis

“If I had a kidney problem, I should have signs telling me things aren’t right.”

Several patients expressed shock and frustration at receiving a new diagnosis of a chronic illness in the absence of any bothersome symptoms. Concerns regarding the permanence and potential reversibility of the disease were also expressed.

Diverse beliefs on disease causation

“…if someone has a kidney problem, that’s when he was ‘caught’… like black magic.”

Teasdale et al suggest that patients may have beliefs on disease causation that are unique to their culture or socioeconomic strata. An Australian aboriginal woman’s viewpoint, demonstrated above, stood in contrast with the beliefs expressed by participants from less marginalized groups. Those individuals seemed to blame their diagnosis on personal bad habits, such as stressful lifestyles or increased alcohol use. Others pointed to hereditary causes, mentioning a parent with diabetes as the inciting factor.

Diverse beliefs on disease progression

“…in three or four years I won’t be able to work… won’t be any money to pay for this and that. Who’s going to drive me?”

Patients lamented the social and financial burden of having a chronic illness. Concerns included the desire for financial independence, the need to be able to physically work, and the perceived disease burden on a significant other. Some patients channeled these concerns into a motivating force and were able to adopt increasingly healthful behaviors. Others were less upbeat, citing complex medication regimens, comorbid conditions, and an advancing age as barriers to adopting healthy lifestyle changes to halt disease progression.

Unmet information needs

“… information should be offered in the beginning, it shouldn’t be withheld… it’s much harsher to find it out in the end.”

Some patients felt that physicians were intentionally withholding information. Several expressed a desire for their physicians to provide more practical CKD management advice using clear, disease-specific terms, educational materials, and peer support groups.

Unmet psychosocial needs and coping strategies

“I felt trapped, I can’t go out anymore, I used to like going out, travelling, fishing, but I can’t do that anymore, I just don’t feel like it.”

At more advanced stages of CKD, patients expressed significant restrictions in their freedom and social activities. Specific frustrations included fatigue, feeling dependent on others, and having difficulty maintaining social appearances. Patients also highlighted coping mechanisms such as having social support and cultivating a sense of community as key factors in having an acceptable quality of life. The ability to emotionally adjust to a “new normal” was also deemed necessary in order to regain some sense of control.

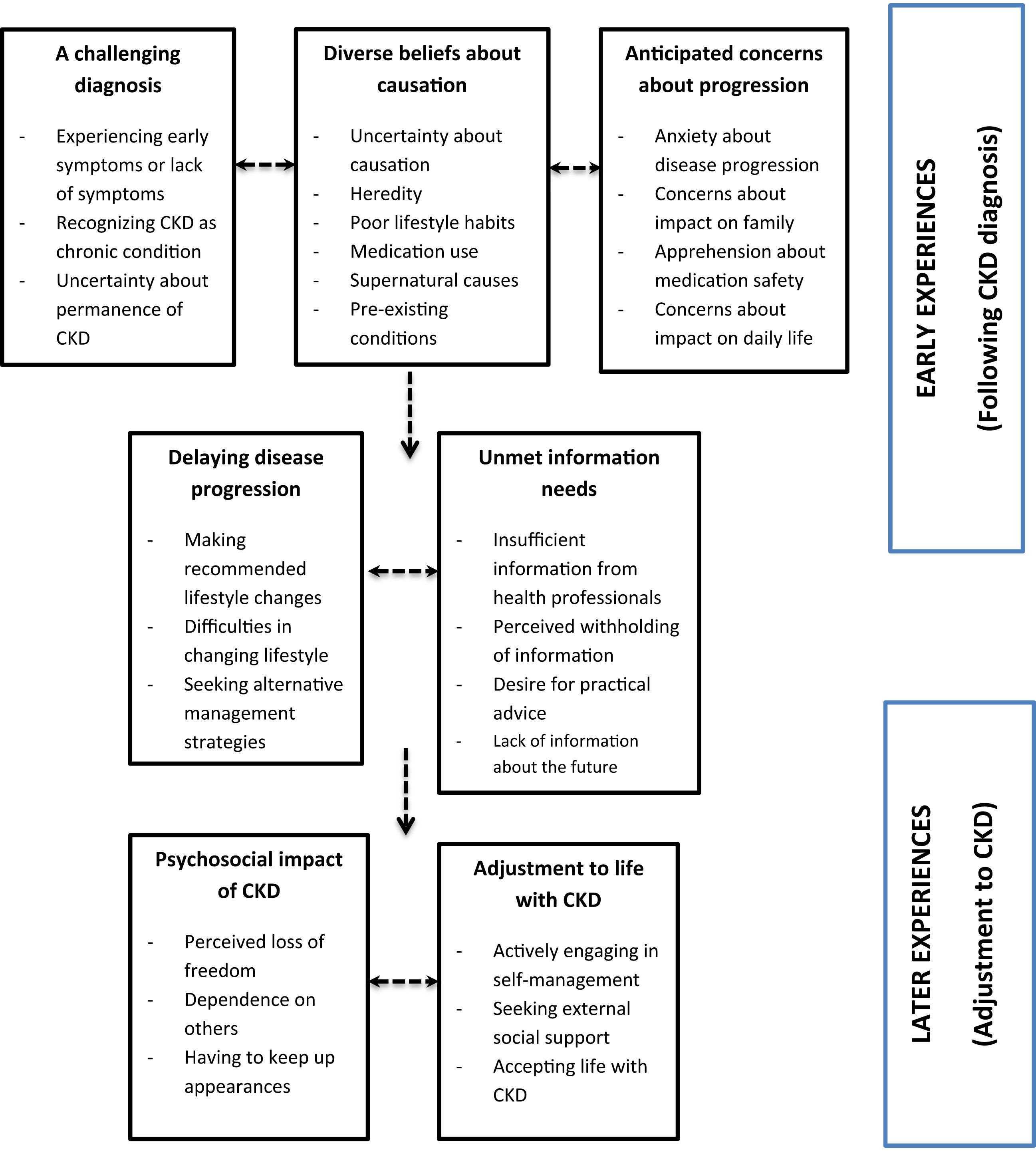

Key themes and subthemes. Arrows indicate the authors’ interpretation of how patients move between stages of understanding and adjusting to CKD. Figure 3 from Teasdale et al, AJKD © National Kidney Foundation.

Teasdale et al highlighted the need for further research into the psychosocial aspects of advancing CKD, including longitudinal studies of patients’ evolving needs. Additionally, as the authors thoughtfully pointed out, much of the existing qualitative literature treats CKD as a single entity, when other co-existing illnesses must also have effects on a patient’s quality of life. As many of the participants in the studies included lived in high-income countries, future studies should attempt to elicit perceptions of low-income patients.

This review is also unique in that despite the heterogeneity of studies it includes, it provides some evidence that patients may have stage-specific concerns as they navigate the process of living with CKD. Though these needs undoubtedly overlap, it seems that during earlier stages of CKD, patients lack awareness about their disease, have culture-specific beliefs about causation, and worry about disease progression. Further along their disease course, patients struggle with the psychosocial stress of having a chronic, progressive illness and attempt to adopt various coping mechanisms.

What implications do studies like these have for us as providers? To me, they highlight the need for physicians to be cognizant of the complex, interrelated relationships that exist between these themes and their potential effects on patients’ medical decision-making. To help address these concerns, existing efforts to increase screening for at-risk populations should continue to be implemented. Educational materials that are appropriate to patients’ literacy level should continue to be used and further developed. Culturally-sensitive tools to elicit the coping strategies and alleviate the psychosocial stresses of patients with advanced CKD need to be created. Continuing to address these issues will help facilitate high-quality, clear, and effective patient-provider communication. Such interventions also have the potential to manage conflicts that may arise when patients must select between dialysis modalities, choose among different types of access, or opt for conservative management.

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are increasingly being recognized as a critical component of clinical research in nephrology. As qualitative analyses have the ability to provide rich, patient-centered data, they may help identify additional elements involved in the illness experience of individuals with kidney disease and, as a result, inform future research endeavors.

– Post written by Devika Nair (@devimol), AJKDBlog Guest Contributor and Nephrology Fellow at VUMC, with support provided by Beatrice Concepcion, AJKD Social Media Advisory Board member.

To view the Teasdale et al article abstract or full-text (subscription required), please visit AJKD.org.

Title: Patients’ Experiences After CKD Diagnosis: A Meta-ethnographic Study and Systematic Review

Authors: E.J. Teasdale, G. Leydon, S. Fraser, P. Roderick, M.W. Taal, and S. Tonkin-Crine

DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.05.019

Leave a Reply