Complications From Tunneled Hemodialysis Catheters

A recent publication in AJKD examines the issue of complications from tunneled hemodialysis catheters in Canadian dialysis patients. AJKD Social Media Editor, Dr. Timothy Yau (AJKDBlog), interviewed one of the authors, Dr. Matthew Oliver (MO).

AJKDBlog: You start the paper by describing the use of central venous catheters (CVCs) in Canada. One interesting statistic that jumped out was the 45% prevalence which was reported in DOPPS II. What are the main reasons for this higher incidence when compared to the US and Europe?

MO: The reasons for high catheter use in Canada are unknown. One possible explanation is that the risk of complications associated with catheters is lower in Canada. The primary goal of this paper was to describe this risk in detail. We wanted to go beyond just looking at access use patterns and analyze the complications from the use.

For example, catheter-related bacteremia rate is under 0.5 per 1,000 catheter days in many centers. Nephrologists may intuitively understand this lower risk and therefore accept the use of catheters. In general, financial incentives to remove lines and use AV access are not in place in Canada. We do not exist in the same pay for performance environment as the US and we do not have a fistula first program operating in Canada at the national level. That said, we do generally promote the use of fistulas and avoidance of catheters but perhaps in a less aggressive way than the US. In addition, we may be more likely take patient preferences into account and many patients prefer to use catheters.

AJKDBlog: Your primary source was the Dialysis Measurement Analysis and Reporting (DMAR) system. Can you give us a little background on the types of data the system is tracking?

MO: The DMAR system was actually co-invented by myself and co-author Dr. Robert Quinn. Its purpose was to bring the rigor of clinical trials to quality improvement in dialysis. It tracks major adverse events in dialysis patients. Similar to a clinical trial, all data are reviewed by a central coordinating center by experts. This maintains data standards across sites. We also track all access procedures and hospitalizations and relate these events to a specific cause. Arbitrated cause was done prospectively by communicating with front line nurses in the programs. Access procedures in chronic dialysis patients are complex and it was very helpful to have a longitudinal record of all access procedures and their indications that was carefully reviewed.

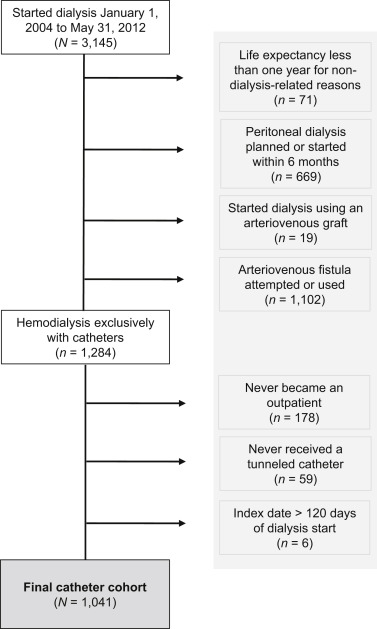

Cohort creation flow chart. Figure 1 from Poinen et al, AJKD, © National Kidney Foundation.

AJKDBlog: What was the outcome you chose to study, and what were the reasons your group decided on this?

MO: The outcome of the study was catheter-related complications. We detected these complications by reviewing all access procedures, hospitalizations, and deaths to determine if they were catheter-related. This method provided a good window into the burden of catheter-related complications in patients in Canada using catheters. We acknowledged that we did not capture catheter-related complications not associated with these outcomes (e.g. low blood flow, thrombolytic use in the HD unit) but our outcomes should detect the most important complications.

AJKDBlog: Of the 1,000+ patients included in the final cohort, what did you find with regards to CVC use?

MO: The main results found the cumulative risk of any catheter-related complications was 30% at 1 year and 38% at 2 years. The one- and two-year risks of bacteremia were 9% and 11%, respectively. Bacteremia was responsible for 72% of catheter-related hospitalizations. The one- and two-year risks of central venous stenosis or thrombosis were only 1.5% and 2.5%, respectively, but they were responsible for 10% of hospitalizations. The one- and two-year risks of blood flow restriction were 15% and 18%, respectively. Blood flow restriction was responsible for 35% of procedures, but did not result in any hospitalizations.

These results can be used to inform patients more accurately of the risks of using a catheter. Some may view this as a glass half-full or half-empty scenario. While 2/3 had no complications, approximately one in 10 had a bacteremia and some of these bacteremia were very serious and could rarely lead to death. I always make sure my patients who want to use catheters are aware of these serious complications but I also admit some patients can be complication-free with catheters. This is a more balanced view of catheters rather than just stating catheters are not an acceptable form of access.

This framework could also be used in other programs or regions to calculate local risks. I personally find the cumulative risk at one and two years easier to explain to patients than rates.

Cumulative incidence of catheter-related events. Percentage of patients who have experienced at least 1 catheter-related event from the time of tunneled catheter insertion (in months). The top black line is the first of any catheter-related event (eg, bacteremia or inflow/outflow) while the other lines are cause specific (eg, first bacteremia irrespective of other complications). Death, transplantation, recovery, and starting peritoneal dialysis therapy were considered competing events. Censoring events were transfers, losses to follow-up. or end of study follow-up. Figure 2 from Poinen et al, AJKD, © National Kidney Foundation.

Frequency of catheter-related procedures and hospitalizations by cause. A breakdown of all catheter-related (left) interventions and (right) hospitalizations by their primary causes: bacteremia, other infection, central venous stenosis or thrombosis, inflow/outflow, or other. Complications up to 2 years are reported. Figure 3 from Poinen et al, AJKD, © National Kidney Foundation.

AJKDBlog: It’s important to note that you excluded patients that had AV access placed shortly after dialysis initiation, so that morbidity could be attributed to the catheter. In this regard, I found this study very helpful in explaining risk to patients. I’ll often address issues like stenosis/thrombosis, infection risk, etc. with them. It’s very helpful to say there is a 30% likelihood that something like this will happen within a year if they keep this catheter. How does your study’s risk estimate compare to other studies?

MO: We wanted to study a “pure catheter” cohort so we knew all access complications were likely related to the catheters. Once you introduce AV access, the complexity increases and you would have to arbitrate if complications are related to the catheter, AV access or both. However, it could introduce bias by excluding patients who had an AV access. We acknowledged this limitation in the discussion.

It is hard to compare these results to other programs because often results are presented differently but one study from the US found the risk of both infection and flow restriction to be 2- to 3-fold the risk of this study. It is important to understand your local risks so you can communicate them to your patients. And if local catheter risks are high this does justify a more aggressive promotion of AV access. Perhaps this study will provide some guidance as to how to track and report risks of catheters in the future.

AJKDBlog: You also found that elderly patients were at lower risk for CVC-related complications. As you point out, this may make the option of a CVC more acceptable in older patients who have limited life expectancy. What are your thoughts on this finding?

MO: Often, older patients are more concerned with the quality of their life, avoiding pain, and avoiding surgery, so they might find catheters a reasonable access choice. It is also possible that catheters have fewer complications because they are less active than younger patients. We think it is very important to study the risks of catheters in older patients because it is possible the risks are lower so respecting their wishes to have one is reasonable. In this study, the risk of complications was slightly lower in the elderly patients.

Table 3 from Poinen et al, AJKD, © National Kidney Foundation.

AJKDBlog: Any final takeaway points or ongoing research looking at these questions in more detail?

MO: The main takeaway is we should not use access use as a surrogate for quality. In the absence of randomized controlled studies, we need to carefully review the complications that result from access use and different access choices.

This study showed that catheter use in Canada is likely associated with a reasonable risk profile in part explaining the higher catheter use in Canada. The next step is to carefully compare this risk profile to those patients who did choose to have an AV access created to see how it modified the risk. We also have to match access choices with patient preference where possible.

AJKDBlog: Thanks so much for doing this interview!

To view Poinen et al, please visit AJKD.org.

Title: Complications From Tunneled Hemodialysis Catheters: A Canadian Observational Cohort Study

Authors: K. Poinen, R.R. Quinn, A. Clarke, P. Ravani, S. Hiremath, L.M. Miller, P.G. Blake, M.J. Oliver

DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.10.014

Leave a Reply