#NephMadness 2023: Transgender Health Region

Submit your picks! | NephMadness 2023 | #NephMadness | #TransgenderRegion

Selection Committee Member: Mitchell R. Lunn @MitchellLunn

Mitchell R. Lunn (he/him) is an Assistant Professor of Medicine (Nephrology) and of Epidemiology and Population Health at Stanford University School of Medicine. He combines his interest in sexual and gender minority (SGM) health and technology to design and deploy digital solutions for address issues related to participant engagement, recruitment, and retention. Dr Lunn is the co-director of PRIDEnet, a national community engagement network focused on catalyzing SGM health research including for the NIH’s All of Us Research Program. He also co-directs The PRIDE Study, a national longitudinal cohort study of SGM adult health.

Writer: Sehrish Ali @sehrish_alii

Sehrish Ali is an Assistant Professor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, TX, where she completed her fellowship under the Transition of Care clinical pathway. At BCM, she serves as the Associate Program Director of Nephrology Fellowship. Her clinical interests include women’s health and kidney disease, gender disparities and kidney disease, education, and wellness.

Totini Chatterjee is a nephrology fellow at the Baylor College of Medicine. She completed medical school at Texas Tech University in Lubbock. She is a graduate of the combined Internal Medicine-Geriatrics residency and fellowship program at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Her clinical interests include disparities in kidney care.

Competitors for the Transgender Health Region

Team 1: Kidney Care for the Transgender Patient versus Team 2: Gender-Affirming Care

Copyright: nito/Shutterstock

The term “sexual and/or gender minority” (SGM) describes a diverse range of individuals, including those with a difference in sex development and individuals that may identify themselves as asexual, two-spirit, intersex, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or other minority sexual and/or gender identities (LGBTQ+) (Table 1).

The sex assigned to someone at birth, usually based on a person’s primary sexual characteristics (eg, external genitalia), may not correspond with an individual’s gender or sexual identity or expression. Table 1 summarizes the terms individuals may use to self-identify.

Health inequities and unequal access to healthcare are prevalent in the LGBTQ+ community. In a recent study by the Center of American Progress, 15% of 1528 self-identified LGBTQ+ respondents endorsed postponing or avoiding medical treatment due to fear of discrimination. The respondents who identified as transgender reported an even starker reality, with 30% reporting postponing or avoiding medical treatment due to fear of discrimination. One-third of respondents reported the need to teach healthcare providers about their sexual identity to receive adequate care (Figure 1). Care for patients with kidney disease is unfortunately impacted by various social determinants and health disparities, and LGBTQ+ patients are susceptible to added barriers and negative physical, mental, and behavioral consequences. Greater awareness and education are necessary to overcome these added factors.

Figure 1. Discrimination prevents LGBTQ people from accessing healthcare

Many LGBTQ+ individuals may conform to societal pressures by hiding their sexual orientation and gender identity. In the United States (US), health surveys offer a limited assessment of the LGBTQ+ community, as they do not regularly include questions on sexual orientation and gender identity. Based on the current collected data, 0.7% of the US population identifies as transgender. Out of 26 million people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the United States, 78,000 people (0.3%) identify as transgender, and approximately 2,500 transgender people receive dialysis.

Over the last several years, there has been growing awareness of gender-affirming care. It is everyone’s responsibility to create a more inclusive environment by examining the roots of the discrimination, stigma, and violence that the LGBTQ+ community continues to face. This NephMadness region, making its debut in the tournament, highlights both kidney care for the transgender patient and the impact of gender-affirming care on kidney health, with the ultimate goal being to ensure health equity and improved access to healthcare.

Team 1: Kidney Care for the Transgender Patient

In the current healthcare system disparities exist based on socioeconomic class, ethnicity/race, educational status, and gender identity. In medical school, there is a lack of education on how to address and acknowledge individuals in the LGBTQ+ community. Similarly, graduate medical education programs such as residencies and fellowships offer limited training on how to address some disparities, which can result in non-comprehensive care.

Transgender individuals may begin their social transition in the community by using a new name or pronoun. Individuals may use gender-based pronouns such as he/him/his or she/her/hers, or gender-neutral pronouns like they/them/their or ze/zir/zirs. Some may express their gender through their clothing, hair, make-up, mannerisms, etc. If the sex listed on a person’s medical record differs from their gender identity, the medical staff and/or the physician may incorrectly address a patient with the wrong pronouns. This could damage rapport between the patient and healthcare team, lead to the patient feeling disrespected, and ultimately result in mistrust of their healthcare providers. The ramifications of this mistrust can further lead to substandard patient outcomes. Understanding and being comfortable caring for those identifying as LGBTQ+ is one way to create a safe and affirming environment for patients.

Copyright: Lightspring/Shutterstock

Patients in the LGBTQ+ community may already be susceptible to barriers such as neglect, financial instability, and discrimination, along with a lack of acceptance by healthcare providers who are not well informed/trained about the LGBTQ+ community. In a study of transgender patients who visited a physician in the past year, 29% were refused to be seen due to their gender identity, and 29% experienced unwanted physical contact from a healthcare professional.

Along with disparities in receiving and/or accessing healthcare, the LGBTQ+ community faces mental health challenges. Some individuals face gender dysphoria, a term describing uneasiness perceived by a person due to the mismatch between their gender identity and sex assigned at birth. This may be seen in transgender and gender minority individuals who may use negative coping mechanisms and become prone to suicidal thoughts, mood disorders including anxiety, and eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa. Patients with anorexia nervosa are more likely to have electrolyte derangements and to develop acute kidney injury and CKD. It is imperative for us as nephrologists to be aware and proactive in addressing these concerns with our patients to improve overall care.

Bathrooms are a concern of homophobic or transphobic people. Traditionally, bathrooms have been gender-based (ie, men or women), a reflection of society’s cisnormative expectation that people will use bathrooms based on their assigned sex at birth. As a result, someone who is transgender or identifies as non-binary may not feel comfortable going to the bathroom consistent with their gender identity due to the fear of harassment, embarrassment, or negative reception by others. More recently, many hospitals have started adopting policies where patients may use whichever restroom matches their gender identity. Other hospitals and institutions have adopted the use of gender-neutral bathrooms, which can be used by anyone regardless of gender identity. The harassment of patients using hospital bathrooms in accordance with their gender identity is not to be tolerated; however, almost 60% of transgender Americans have avoided using public restrooms for fear of confrontation due to harassment and assault. Additionally, to our knowledge, dialysis facilities, and clinics have yet to incorporate gender-neutral restrooms, which can provide inclusiveness and a welcoming atmosphere for transgender patients receiving dialysis.

As in the general population, it is equally important to understand the prevalence of other comorbidities for LGBTQ+ individuals with CKD and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), especially for those who receive gender-affirming hormonal therapy (GAHT).

For example, although the risk of fractures is elevated in the general CKD population, this risk may be variable by the sex assigned at birth and can be influenced by the use of exogenous hormones in GAHT. In a study of transgender individuals who received long-term GAHT, fracture risk was found to be higher in younger (age <50 years) transgender women compared to a cohort of age-matched cisgender women. Conversely, fracture risk was not increased in younger transgender men compared to age-matched cisgender men.

Furthermore, there have been various studies showing the increased prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and cardiovascular-related outcomes in transgender men and women in comparison to cisgender men and women. GAHT may affect the risk of many chronic conditions. For example, transgender women have a decrease in blood pressure after receiving GAHT, whereas transgender men have an increase in blood pressure. Cerebrovascular complications such as venous thromboembolism, cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction, and unstable angina have been noted to be higher in transgender women who have received gender-affirmation therapy compared to cisgender women. These same complications are lower in transgender men, who have received gender affirmation therapy, in comparison to cisgender men. Diabetes risk is higher in transgender women and men on GAHT in comparison to matched cisgender women and men, respectively.

About 13.7% of transgender individuals in the United States have HIV. The risk of HIV is increased in transgender individuals; however, there is a disparity in the access to care and prevention between transgender and cisgender individuals. Preventative medications and treatments for HIV have been understudied in transgender individuals on GAHT. While there may be concern for interaction between these drugs and the metabolism of GAHT, additional information and research is needed to improve care for the transgender population.

Kidney Function Estimation

Another challenging area of clinical interest is the lack of evidence-based guidelines on assessing the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) via serum creatinine for a transgender person who is receiving GAHT. The effect of sex is known on serum creatinine in the cisgender population. However, for a transgender person on GAHT, muscle mass or body fat distribution may be affected, which would make it difficult to correlate the serum creatinine between transgender patients and their age-matched cisgender counterparts. Studies have shown changes in serum creatinine in transgender individuals who have received GAHT. Calculated equations for eGFR using serum creatinine currently use a sex coefficient based on cisgender data, which may underestimate kidney function in transgender adults on GAHT. Future research on the use of 24-hour urine collection for creatinine and urea in the LGBTQ+ population may provide more accurate renal function measurements than spot serum measurements.

Additionally, using a sex-based rather than a gender-based reference range for serum creatinine may be viewed as offensive. Non-sex dependent biomarkers may be more inclusive of the LGBTQ+ community in measuring kidney function. Utilizing serum cystatin C is one alternative marker to assess eGFR for transgender patients independent of muscle mass. However, other factors such as infection, obesity, tobacco use, corticosteroids, and hyperthyroidism may influence serum cystatin C and would need to be taken into account for each patient. To directly measure GFR, filtration markers such as iohexol, iothalamate, chromium-51 ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (Cr-EDTA), or “gold standard” inulin can be administered. Limitations of using exogenous filtration markers like inulin may include limited availability, invasiveness, and cost.

Until standardized surveys and tools are created to effectively assess gender and sexual identity for each individual in a culturally sensitive manner, we can collect this information from our patients ourselves. This can be done by creating a welcoming, interpersonal environment and avoiding assumptions of gender identity. Starting a conversation by sharing one’s own pronouns and respectfully asking about the patient’s pronouns is one way to collect this information. Additionally, documentation of both current gender identity and sex assigned at birth in the medical records at the beginning of every visit will promote the delivery of high-quality care to transgender individuals. Strategies to nurture a welcoming LGTBQ+ environment within clinics and outpatient dialysis centers include hiring LGBTQ+ staff, displaying physical LGBTQ+ symbols (such as flags, pins, and stickers), creating non-gendered restrooms, and including LGBTQ+ people on posters or signs.

In conclusion, as the transgender population grows, nephrologists must stay informed on not only the challenges this population faces but also the ways in which we can improve their care. It is of utmost importance to become more familiar with the unique challenges that may be affecting their mental and physical health.

COMMENTARY BY MURDOCH LEEIES:

Transgender and Gender Diverse Identities in Nephrology

Check out this podcast episode of The Nephron Segment featuring Mitchell Lunn and Sehrish Ali :

Episode 9: Transgender Health & NephMadness 2023

Team 2: Gender-Affirming Care

Gender-affirming care is multifaceted and encompasses social, medical, and surgical changes which transgender and other gender-diverse individuals may choose to navigate. While some choose medical or surgical treatments, others may elect to avoid medical or surgical transition; some non-binary individuals may microdose during the medical transition. Hence, the path of each person is unique. Nephrologists and kidney care professionals have a responsibility to understand the importance of gender-affirming therapies and their implications for our transgender patients.

Copyright: New Africa/Shutterstock

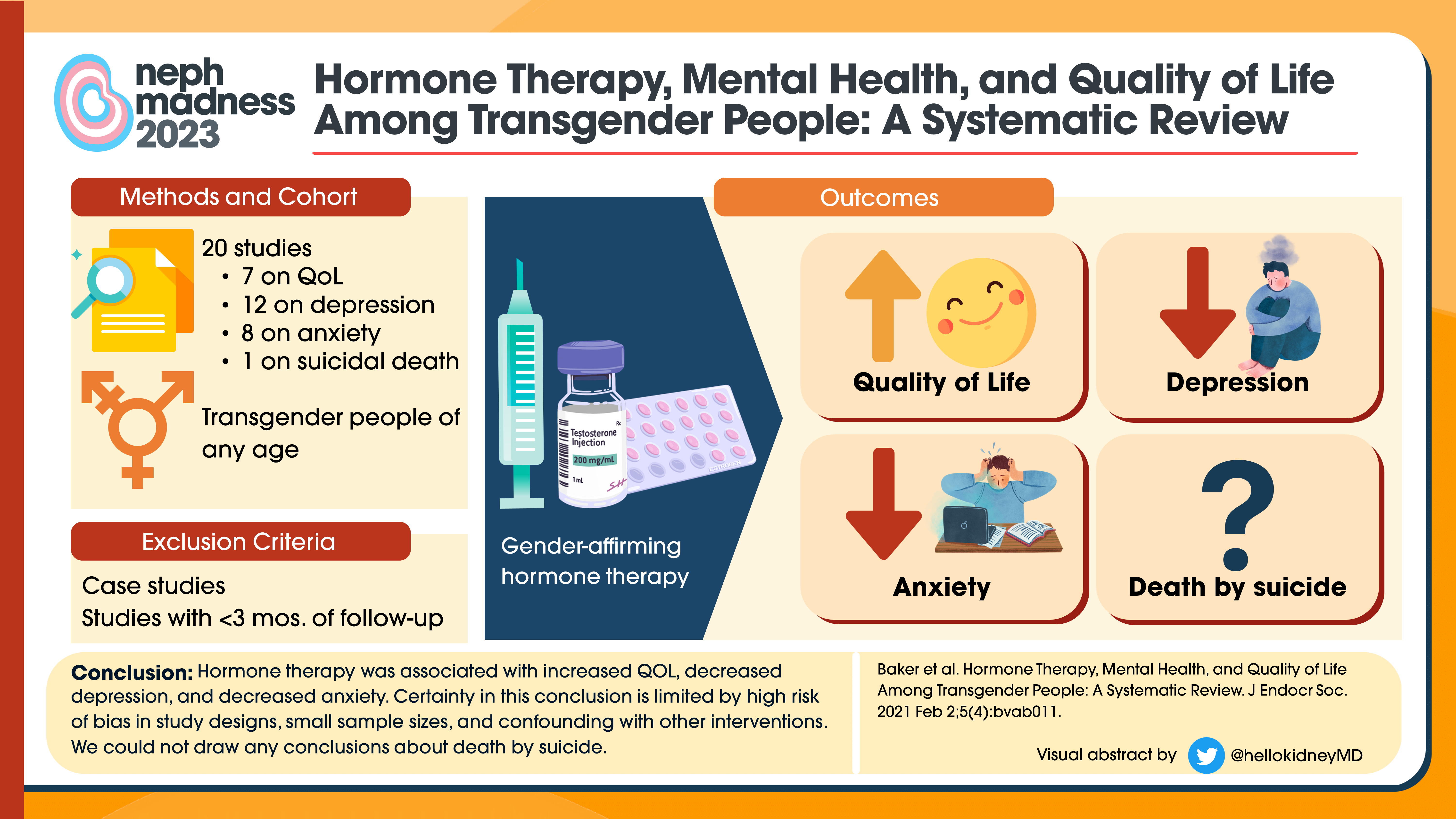

Undergoing gender-affirming therapy is a major change in a patient’s life, both physically and mentally. GAHT for transgender men typically consists of injectable or transdermal testosterone therapy, and GAHT for transgender women includes exogenous sublingual, oral, transdermal, or injectable estradiol, typically along with anti-androgen therapy. Studies have found that initiating this treatment can lead to improvements in quality of life, anxiety, and depression in transgender patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hormone therapy, mental health and quality of life among transgender people

Figure 2. Hormone therapy, mental health and quality of life among transgender people

GAHT may have a direct and indirect effect on creatinine because it may impact muscle mass and body fat. Since, as previously discussed, GAHT has been linked with changes in kidney function and can impact eGFR, it will be important to ensure accurate measurement of kidney function in these individuals. This can be accomplished by knowing when and how to employ techniques such as 24-hour urine creatinine and urea collection, cystatin C, or direct (eg, inulin, iohexol) clearance measurement.

Testosterone therapy has been associated with changes in serum creatinine, but there are limited studies to show its effect on kidney disease. One relationship between testosterone and kidney function was illustrated in a case report of a 14-year-old cisgender boy who received testosterone therapy, which resulted in a rise in both serum cystatin C and creatinine. After cessation of testosterone injections, both kidney biomarkers decreased and remained stable for six months. This change in serum cystatin C and creatinine is thought to be induced by testosterone-mediated changes in intrarenal hemodynamic parameters. Alternatively, another observational cohort study showed long-term testosterone therapy to be associated with an improvement in kidney function for cisgender men with low endogenous testosterone levels (Figure 3). This study did not specifically target individuals with established CKD. While the evidence may not be clear, testosterone may impact kidney function.

Figure 3. The impact of long-term testosterone therapy on renal function among hypogonadal men

Figure 3. The impact of long-term testosterone therapy on renal function among hypogonadal men

In a research trial studying the effect of estradiol on serum creatinine in transgender patients, transgender women participants had a decrease in their serum creatinine within six months of starting estradiol treatment. Conversely, in transgender men participants, their serum creatinine increased within six months of starting testosterone treatment. After twelve months of receiving GAHT, serum creatinine levels were more similar when compared by gender identity rather than by sex assigned at birth. The changes in serum creatinine correlate with individual changes in body composition and lean body mass, which occurs in response to GAHT.

In a recent study, the effect of GAHT on transgender patients (488 adult transgender men and 529 transgender women) was evaluated. With the initiation of GAHT, the serum creatinine increased in transgender men but did not significantly change for transgender women (Figure 4). Whether these changes in creatinine are representative of true changes in GFR remains to be seen. Further studies are needed to elucidate other underlying changes associated with kidney function (eg, other biomarkers) that are important for estimating kidney function.

Figure 4. The effect of gender-affirming hormone therapy on measures of kidney function

Figure 4. The effect of gender-affirming hormone therapy on measures of kidney function

Furthermore, certain GAHT therapies may be associated with other factors that impact kidney health such as changes in hemoglobin and hematocrit. Transgender men receiving testosterone therapy may have stimulated erythropoiesis and cessation of menses. However, if a non-binary person assigned female sex at birth on low-dose testosterone therapy still has menstruation, the hemoglobin levels may be impacted by menstrual blood loss. Transgender women, on the other hand, may receive exogenous estradiol, which will cause testosterone levels to fall. Consequently, these individuals often experience some testicular atrophy. However, others may still have some residual testicular function, which may release pulsatile androgen activity and improve hemoglobin levels.

Spironolactone is a commonly used anti-androgen component of GAHT therapy in transgender women which blocks testosterone’s effect at the tissue level; this blockade helps promote breast development. In those with advanced CKD, close monitoring of kidney function, electrolyte derangements, and hypertension management is essential for those on spironolactone, given its association with hyperkalemia and acute kidney injury.

Although GAHT alone may be an acceptable option for some individuals, others may opt for a surgical component as part of their gender transition (Tables 2, 3). Genital surgeries including the removal of genital organs are additional surgical procedures that may be pursued. There are over 25 different gender-affirming procedures and surgeries that individuals can receive. Description and complications of selected surgical procedures available for transgender men and women are listed in Tables 2 and 3. Other common procedures include masculinizing chest reconstruction, facial masculinization/feminization surgery, orchiectomy, or chondrolaryngoplasty (“tracheal shave”).

Table 2. Common reconstructive procedures for transgender men

| Surgery | Description | Complications |

| Phalloplasty | Neopenis construction using a skin graft from a person’s arm, thigh, abdomen or back | Uncontrolled bleeding, hematoma, infection, scar tissue, urethral stricture, difficulty with urination, vascular thrombus formation, skin graft failure |

| Neopenis construction from the enlarged clitoris | Uncontrolled bleeding, infection, scar tissue, urethral stricture, difficulty with urination, cutaneous fistula | |

| Implantation of a prosthesis after phalloplasty. Most common types are malleable or inflatable | Uncontrolled bleeding, infection, scar tissue, corporal perforation, urethral stricture, difficulty with urination |

Table 3. Common reconstructive procedures for transgender women

| Surgery | Description | Complications |

| Breast enlargement using implants and fat grafts. Common implant options include saline or silicone injections | Acute kidney injury or hypercalcemia with silicone injections, scar tissue, breast pain, nerve injury, asymmetry, hematoma, infections | |

| Neovagina construction from genital or abdominal tissue. Common options include penile inversion, colonic and peritoneal pull-through | Vaginal stenosis, fistula, urethral stricture, urethral malposition, graft/flap necrosis, deep vein thrombosis, hematoma, nerve injury, urinary tract injury, scar tissue | |

| Neovulva construction from scrotal and urethral tissue | Fistula, urethral stricture, urethral malposition, abscess formation, graft/flap necrosis, deep vein thrombosis, hematoma, nerve injury, urinary tract injury, scar tissue |

Impact of GAHT on AKI & CKD

Gender-affirming medical and surgical therapies are becoming more prevalent in our community. However, they have a unique set of risks and side effects.

A recent cross-sectional study showed a lower prevalence of acute kidney injury and CKD in transgender individuals on GAHT in comparison to those not on GAHT. However, ongoing investigation and research is needed in this arena to determine how best to assess kidney function in transgender individuals, as current data are limited. This evaluation has important implications for dosing medications and for guiding prognostication and management of a transgender patient with kidney disease.

The impact that GAHT may potentially have on kidney biomarkers is important to recognize in the nephrology community as we classify our patients in different stages of CKD, give recommendations on medication dose adjustments, initiate them on renal replacement therapy, and evaluate them for kidney transplantation. Furthermore, estrogen therapy (especially oral formulations) may increase the risk for venous thromboembolism and cardiovascular disease in patients that have CKD, who are already at risk for these disease processes without estrogen therapy. Educating these patients on the risks and benefits of gender-affirming care and its impact on their kidney health is crucial. This may have an additional positive impact on patient adherence and satisfaction.

Adequate social and structural support is also crucial. The transitioning process may feel stressful, daunting, and isolating. Patients with kidney disease are already identified as having an increased risk of depression and other mental health illnesses. They may feel alone and without support or an advocate. Gender-affirming care (whether medical or surgical) with the proper social and structural support may improve mental health. This may be due to improved trust, access to care, and all-together well-being. It may also improve overall patient outcomes and encourage freedom of expression. With this population seeking more medical care, chronic disease prevention, and acute illnesses may be treated earlier. It may be beneficial to collaborate and develop a multidisciplinary team approach to improve the knowledge, satisfaction, and medical outcomes of these vulnerable patients. This will allow shared decision-making, reduce societal stigma, and improve quality of life by eliminating barriers and empowering a community that may otherwise feel neglected.

Conclusion

In summary, gender-affirming care may include the medical and surgical interventions described above for some individuals, though others may opt not to pursue these options. Gender-affirming care has implications for all elements of kidney care, including kidney function estimation, CKD, and transplantation. Kidney care professionals will be better equipped to provide high-quality care to all our patients with a greater understanding of gender-affirming therapies and their implications for kidney health.

– Executive Team Members for this region: Pascale Khairallah @Khairallah_P and Samira Farouk @ssfarouk

How to Claim CME and MOC

US-based physicians can earn 1.0 CME credit and 1.0 MOC per region through NKF PERC (detailed instructions here). The CME and MOC activity will expire on June 1, 2023.

Submit your picks! | #NephMadness | @NephMadness | #TransgenderRegion

Leave a Reply