#NephMadness 2019: US Hypertension Guidelines – Bold for Certain, Benefits to be Determined

Doreen Rabi @doreen_rabi

Doreen Rabi is an academic endocrinologist and cardiovascular health outcomes researcher at the Cummings School of Medicine, the O’Brien Institute for Public Health, and the Libin Cardiovascular Institute at the University of Calgary. She is a Canadian leader in national guidelines for cardiovascular risk reduction. Dr. Rabi is the co-chair of the 2018 Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Methods Committee and has been the chair of the Hypertension Canada/CHEP recommendations since 2016. Dr. Rabi also participates on the Canadian Cardiovascular Guidelines Harmonization Endeavour (C-CHANGE) committee.

Competitors for the Hypertension Region

EU Guidelines vs US Guidelines

Hyperaldo Diagnosis vs Hyperaldo Treatment

Copyright: JPC-PROD / Shutterstock

The 2017 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults (AKA US Guideline in NephMadness) has taken a bold move in redefining hypertension. The introduction of the US Guideline has made an estimated 31.1 million previously healthy Americans (13.7% of the US population) hypertensive and has identified 4.2 million drug-naïve Americans who should be offered pharmacologic treatment. Those newly classified as hypertensive based on the US Guideline definition are largely lower risk individuals with 80.2% of these adults having a 10-year ASCVD score of <10% (63.5% having a score of <5%).

Low-risk patients with blood pressures (BPs) above the new threshold of 130/80 mm Hg but below the 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines (AKA EU Guidelines in NephMadness) threshold of 140/90 mm Hg are managed conservatively and health behavior change is the primary mode of management (even though adherence to health behavior interventions outside clinical trial settings is known to be low). So while the intent of the guideline may be to catalyze significant lifestyle modification in younger patients, in reality many low-risk patients captured by the new definition will ultimately require pharmacologic treatment.

The rationale for the new diagnostic threshold was related to three independent but related streams of evidence. The first stream comes from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) which demonstrated that adults with established cardiovascular disease (CVD) or high cardiovascular (CV) risk treated at systolic threshold of >130 mm Hg to a target of <120 mm Hg experienced significant CV event and mortality reduction. The second stream of evidence comprise several studies that have been meta-analyzed and demonstrate that there is significant residual CVD risk in those with systolic BPs of >130 mm Hg and that there appears to be additional CV benefit when BPs are lowered below 130 mm Hg. Lastly, there are several prospective studies that demonstrate that BP does increase significantly with age such that persons with higher levels of BP at younger ages have a substantial lifetime risk of hypertension, and by extension, CVD.

Is a shift to defining hypertension at 130/80 mm Hg a move in the right direction?

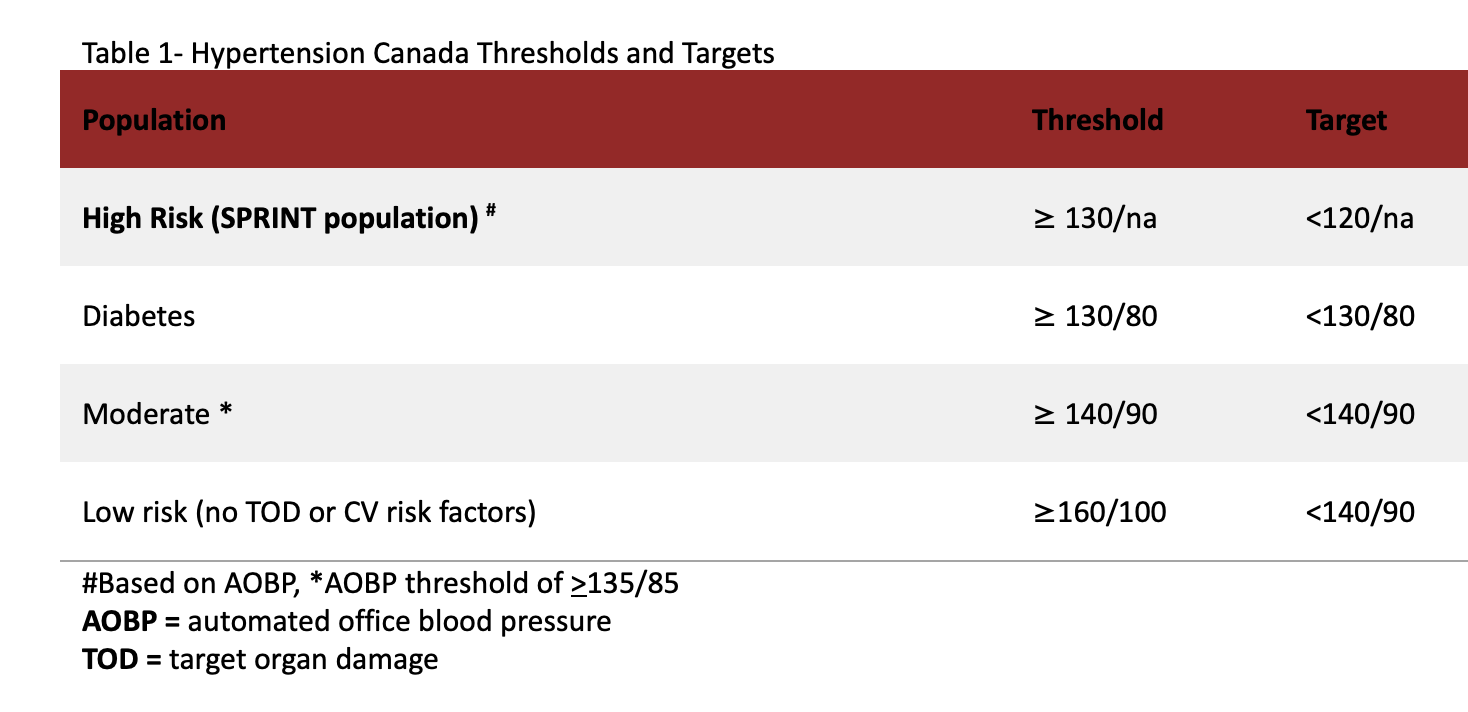

Similar to the US Guideline, Hypertension Canada recommends a treatment threshold of >130/80 mm Hg for high-risk individuals (persons with clinical CVD, non-protenuric chronic kidney disease, those with a 10-year Framingham risk of >15% and those aged 75 years and older); however, the recommended treatment target is a systolic pressure of <120 mm Hg keeping true to the SPRINT intervention. Canada was the first jurisdiction to translate the findings from SPRINT to a clinical practice guideline and feel that there is a strong evidentiary base to support this practice. We also recommend a diagnostic and treatment threshold of >130/80 mm Hg for adults with diabetes. Outside those two very specific and higher risk subpopulations, our guidelines recommend a diagnostic threshold of >140/90 mm Hg for all other adults and have a risk-based treatment thresholds (see Table 1). In these ways, the Canadian Guidelines have a strong resemblance to the EU Guidelines.

It is very unlikely that Canada will adopt the US hypertension definition for several reasons. First, while we do believe there is compelling evidence to support intensive systolic BP targets in high-risk (SPRINT-type) patients, there is very little evidence to support aggressive intervention in lower risk patients. It is estimated that if Canada were to use the US definition, the prevalence of hypertension would jump from 24.2% to 42.4% but the proportion of low- and moderate- risk patients would grow from 53.1% to 68.9% among adults newly identified as hypertensive. While this change would make nearly half of Canadians over the age of 18 years hypertensive, we would be intensifying treatment in a small proportion of patients, making this largely a labeling exercise.

There seems to be a belief that receiving a diagnosis of a CV risk factor such as hypertension or diabetes might help catalyze health behavior change at a patient level, but there is actually little practical evidence that this actually happens. In fact, there is more evidence that such diagnoses have a negative impact on feelings of self-efficacy and wellness that likely undermine health behavior change efforts. Further, we know that health behavior interventions are very effective at lowering BP in the context of clinical trials but are not well-prescribed or supported at points of care.

There should be some concern that changing the demographic profile of hypertensive adults to one that leans to being lower risk could exacerbate the risk-treatment paradox that already exists in the management of cardiovascular disease. Infusing the health care system with younger hypertensive patients that might be anxious about this diagnosis may fuel a desire to treat these patients aggressively. In fairness, the EU Guidelines also encourage that once pharmacotherapy has been initiated, treatment to a target of <130/80 mm Hg should be considered if therapy is well-tolerated in younger patients given the previously stated concern about elevated lifetime risk. Although not intended, a significant lowering of the diagnostic threshold coupled with an emphasis on lifetime risk may lead to intensive treatment of those who will experiences low absolute benefit in the short-term, and divert attention and resources away from older, more medically complex patients who might actually experience an immediate and larger absolute benefit.

The Canadian Guidelines agree with the approach of treating high-risk patients to intensive targets, but disagrees with the actual target identified by the US Guideline. While SPRINT did have a treatment threshold of >130 mm Hg, the treatment target was <120 mm Hg. If high-risk patients are to be treated aggressively, then do so and do so to the target that was explicitly evaluated in the trial. The Canadian Guidelines are also concerned with applying a treatment target of <130/80 mm Hg to all adult patients when this target has not been explicitly evaluated in any trial in any of the subgroups in which it is recommended. Conducting a stratified meta-analysis of BP-lowering trials and observing that people who achieved a systolic BP between 120-129 mm Hg had superior CV outcomes than those who obtained systolic BP between 130-139 mm Hg on treatment do not speak to the value of the target, but do speak to the benefit of a robust response to anti-hypertensive therapy.

Where there is congruence between the Canadian, US, and EU Guidelines is on care process. There is unanimity between guidelines on the importance of accurate BP measurement. There is broad agreement on the value of out-of-office BP confirming hypertension diagnosis and identifying masked and white-coat hypertension. We also agree on the importance of health behavior interventions as a first line management strategy. All guidelines agree that using multi-disciplinary teams can reduce therapeutic inertia and promote adherence. While there is the possibility that these teams could also serve an important health coaching function and support low-risk, hypertensive patients with tailored prescriptions for sustainable lifestyle change, the reality is that health behaviors occur in a socio-cultural context that is often beyond the influence of health care providers. Lifestyle prescriptions do have merit and should be encouraged, but health behavior recommendations also need to be directed to policymakers who can more effectively encourage the development of heart-healthy environments.

Time will only tell if the new US Guideline change to the hypertension definition is a game-changer when it comes to minimizing the negative population health impacts of hypertension in the US. Until then, Canada will continue to stay well within the bounds defined by clinical evidence and will continue to encourage risk-based thresholds and targets for adults patients with hypertension.

– Guest Post written by Doreen Rabi @doreen_rabi

Further Reading: 2018, 2017, 2016, and 2015 Updates to Hypertension Canada Guidelines have been previously summarized by Swapnil Hiremath @hswapnil on the AJKDBlog

As with all content on the AJKD Blog, the opinions expressed are those of the author of each post, and are not necessarily shared or endorsed by the AJKD Blog, AJKD, the National Kidney Foundation, Elsevier, or any other entity unless explicitly stated.

NephMadness 2019 | #NephMadness | @NephMadness | #HTNRegion

Leave a Reply